The 12 Tweets of Christmas

The Second Edition to the Turbulent Twenties Oral History Project

I hesitate to write this commentary, a sequel to my 2021 year in review, for the same reasons a basketball player who sinks his first shot upon stepping onto the court hesitates to shoot another. Looking back at my essay from a year ago, I can say that I had some confidence with what 2021 represented. That is not to mislead. The outlines of the story were so familiar to everyone in my circle it is nothing to boast about. At various points in the commentary, I was doing little more than parroting the analysts I most admire.

Yet, just as any ball player understands exactly what it means to get “in the zone”, my interpretative confidence—no doubt related to my imitative ignorance rather than original insight—engendered a flow state that is impossible to replicate in its absence. I simply sat down at my laptop one night and four hours later it was finished, without any conscious awareness of the intermediate activities required to complete it. PolicyTensor knew exactly how I felt in those hours when he described the post as a fearful “meditation” on modernity. Meandering Meditations on Modernity has a nice ring to it.

Suffice it to say, I don’t anticipate that I will describe a similar subjective experience for the process involved in summoning and cohering my reflections for 2022. In my view, the most essential book of 2022 was left off most of the holiday lists that appeared in the business pages, Erica Thompson’s Escape from Model Land. The book is so essential not because it is more deserving than the other books which won those prizes. Clearly, I am no position to put down Chris Miller’s Chip War. Rather, Model Land is, I think, the umbrella idea for all other useful work being done in 2022. Which strange mixed breed of golden cats on the larger side most closely resemble the “dog” of reality? Riffing off her analysis, to know the present, to say nothing of the future, is always elusive, but in terms of grasping, 2021 was a layup, while 2022 is a half court shot. As I will soon reveal, I do not have the strength to heave it up even in the proximity of the rim. Many of you on this list can surely get much closer, though I have yet to see anybody hit the center of the net.

From my vantage point on the periphery, an interested outside observer who is not in the thick of it, it is clearly apparent that some can locate the center of net, but fail to execute it once they attempt to put into words. The reason why their alchemies are disrupted relate to the nature of the task they are attempting—firmly ontological difficulties rather than contingent ones.1 Even as they fail in interesting ways, I am cheering them on in their pursuit for disciplining a research agenda for an Age of Polycrisis, and remain committed to contributing in my own small intermittent way.

I can hear one of my very first subscribers now, who articulated the major criticism polycrisis proponents must address: wait, doesn’t every moment feel like an Age of Polycrisis to those actors navigating in the midst of things? In a millenarian book, The Great Wave: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History, David Fisher makes exactly this point. Moreover, depending on space-time position within history’s grand auditorium, the directions of those rhythms may be perfectly opposed, periods of price stability punctuated by revolutions, or vice versa? In the introduction, he echoes the essence of the polycrisis mission statement also made in the Focus chapter of Gal Beckerman’s The Quiet Before. The value of assigning numbers and charts to metaphysical phenomena, in the process reducing them into cats, is that the alchemy is useful to us, making god-like thoughts that would otherwise float indefinitely legible to our mortal minds.

The central claim of Fischer’s book is model metaphor favored by the Enlightenment philosophers of stability and equilibrium—of un univers horloge, un dieu horloger one clock universe, one clock god—was a Promethean pursuit that created that reality. But only for a time, Fisher writes. After all, all that is solid melts into the air. And, as we’ll soon explore in the following commentaries, perhaps all falling under the theme, Reflections on Reflexivity, it melts into the air precisely at the moment of its ostensible dominance. That would include the ascent of China in 2001 to solidify the dream of neoliberal globalization, a dream that like post-war Europe’s automobile revolution in the era of American gravity has not exploded but is now deferred. Twenty years later, confidence man SBF announced his arrival weekly with Gisele on the front pages of The New Yorker. That dream of course has now spectacularly exploded. Though I emphasized to PolicyTensor on Twitter a month ago, even after explosions, dreams have a way of repackaging themselves and enduring, particularly when they can attach themselves to a paradoxically durable host, historian Gary Gerstle’s Neoliberal Order (see 1st tweet commentary).

Like Keynes’ essential tract on laissez faire, the aim of these commentaries is not to doubt the usefulness of the clock model metaphor guided by a monotheistic God—of the Rostowian drive to maturity in a unipolar moment. The purpose of social inquiry, Keynes opined in the interwar period, is to operate flexibly and know when reality at first indiscernibly then overtly abandons the model metaphors favored by generations of social science expertise, recognizing them as mere constructions. The Chinese novelist, Qian Zhongshu, wrote that what we call models are fortresses; when the chasm between discourse and reality can no longer be bridged, the fortress swiftly crumbles. With the Russian Army bogged down in a European invasion and the crowning of new monarch in Britain, the signals certainly qualify as overt. The fiction writer, Benjamin Labutat, suggests a powerful fusion between natural philosophy and globality, of physics and history, in When We Cease to Understand the World, interpreting the significance of shattering of Newtonian realm at approximately the same moment as Keynes’ End of Laissez Faire:

Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle shredded the hopes of all those who had put their faith in the clockwork universe Newtonian physics had promised. According to the determinists, if one could reveal the laws that governed matter, one could reach back to the most archaic past and predict the most distant future…merely by looking at the present and running the equations it would be possible to achieve a godlike knowledge of the universe. Those hopes were shattered in light of Heisenberg’s discovery: what was beyond our grasp was neither the future nor the past, but the present itself. Not even the state of one miserable particle could be perfectly apprehended. However much we scrutinized the fundamentals, there would always be something vague, undetermined, uncertain, as if reality allowed us to perceive the world with crystalline clarity with one eye at a time, but never with both.

Recall the point about position, and extending away from price stability to the ultimate determinants of price stability, if Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio is to be believed on the debt cycle, hegemonic stability. Is the natural order of things, as they have been seen since the Industrial Revolution, with the colonial powers spreading its machinations, administration, and linguistic reach in what amounts to a historical blink of an eye, or does that dominance mask a deeper diversity regarding international regimes? Labutat continues in the same vein I explored in my 10,000 neoliberal orders, a transition from the world dominated by cause-effect relations of the “one” and even the “twos” and the “threes” to the tens of thousands of things more familiar to Daoist and Vedic texts:

Where before there had been a cause for every effect, now there was a spectrum of probabilities. In the deepest substrate of all things, physics had not found the solid, unassailable reality Schrödinger and Einstein had dreamt of, ruled over by a rational God pulling the threads of the world, but a domain of wonders and rarities, borne of the whims of a many-armed goddess toying with chance.

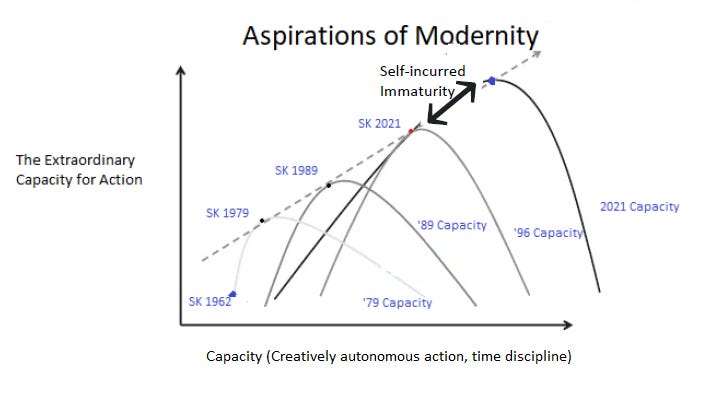

Co-travelers in the world of polycrisis should embrace this world of ontological difficulty for the possibilities it offers, chiefly for those participants left out in the world of exception. The Daoist aphorism that influenced Bertrand Russell when he attended Peking University, in turn, influenced me when I attended nearly 100 years later, “Production without possession, serving others without self-assertion, and development without domination. This is the way of the Dao,” should be the north star to fixing the rot at the heart of the heart2 of the global trading system. Tragically, Jamie Martin's terrific history underscores, international institutions are still beholden to the legacy of the undesirable opposites to each of those elusive aims. Is an international political economy predicated on non-domination possible? Or when temptuous seasons subside in 2040, will we continue to inhabit Machiavelli’s world, both domestically and internationally, divided by conflicting proclivities of elites to dominate and of the non-elite desire to be left alone? Alternatively, can American idealism live up to JFK’s motto to make the world safe for diversity, giving artist nations and peoples alike, to use Bertrand Russell’s classification in The Problem of China, room to move? Or must it expose everybody and everywhere to an insatiable discipline, a self-incurred immaturity, which crowds out the extraordinary capacity for action?

Notwithstanding the reservations I have about writing in 2022, I find myself sitting once again at my keyboard to reflect on the significance of the year that is now almost past. The primary compulsion relates to the personal mission I set forth last December to document the year-by-year structure of feeling in the moment during the critical years for humanity, the Turbulent Twenties and Thirties (we’ll see how far I get). The objective is precisely as Nils Gilman told me last Christmas Eve, to explore “how the tensions and uncertainties of the present politico-economic moment” unfold from our front row seat, not as historians might imagine them in retrospect. Secondarily, I’m reminded that hesitations are a productive impulse. They potentially indicate that, as Gilles Deleuze advised in his abécédaire lectures, that my subconscious is expressing a willingness to enter a universalist project, writing “‘in place of’ the illiterates and barbarians”. A quixotic quest against entropy and the ignorant state of nature. In the end, I am hoping to discover an alchemy from muddled bits to clarity on terms the canonical scholar of attention, Henry James, appreciated:

Recognizing that not all insight comes from Orwellian clarity, inherited by the traditional structure of Oxbridge essay gilds, this exercise is an experiment in the American buffet style of learning. The form of this essay makes explicit to the reader that it is a hodgepodge, a cognitive assemblage, of neurotypically diverse impressions. At the moment, they are little more than impressions.

The cognitive assemblage is such a wonderful model metaphor to replace the clock, because if there is anything that captures the whiplash felt since February 2022, it lies within collective plasticity. While I am no expert on consciousness to assess the merit of this notion to the novel forms of collective mind OpenAI revealed are now advancing at breakneck speed, solid formations are not possible in this crooked corner of the forest. It is about the art of noticing impressions, suggesting a path of where to go next. It is a playful Oakeshottian pursuit within the ruins we find ourselves in at the boundless aperion of History, that which marked the birth of the Daoist triple contradictions and the strange conjuncture on philosophy in 6th century BCE. Positioned across each of these contradictions, I remarked in an essay on China summarizing Carter’s Niebuhrian motivations for normalizing relations, is akin to a rope stretched over the abyss. Or, as Delong has outlined for his personal instruction at Berkeley, A Political Economy for 2040, one that will allow democratic societies to adjust and harness exponentiality they were blindsided by in 2000.

On the first Tweet of Christmas:

Historical time differs from calendar time. They are related—financial panics are more likely to occur in autumn for instance. With our ten digit brains, the first tech bubble was a product of millenarian optimism for the future without regard for fuddy-duddy rules of capital. In the age of disruptive innovation championed by Nikola Tesla, we—those of us who form a speculative community solely around shared belief of our making—do not have to play by those rules. Silicon Valley’s first efflorescence taught those involved that Organization Man can be toppled.

That kind of lesson no doubt left a deep cultural imprint. In the prolonged unwinding of those spectacular gains, Tesla may have lost the battle over Edison, who stands in for regularized investment extending beyond the temporally ephemeral and spatially fragmented, but he won the war. By the end of the 90’s up until 2001, the message of the Apple “1984” commercial was uncontested. The left-leaning economist Joe Stiglitz captured the depth of the shift from the Fordist inclinations of the Age of Control. The world unleashed by the information age was already too complex to control, and government’s duty was to not jeopardize the vital work of disruptors. In this sense, we are all deregulators now, Stiglitz asserted. The rainbow coalition of neo-Victorians, represented by Gingrich, and the new cosmopolitans, represented by Clinton, had coalesced.

Jumping through the vortex of time to Superbowl Sunday in February 2022, viewers may have been struck by the similarity of the moment. As mediated by the key spectacle, the 2022 commercials were, like their 2001 predecessors, a foreboding of what was to come. First as tragedy, then as farce. The positive about tragedies and farces is that they disappear on their own volition. The difference, to be sure, is not a trivial one. Tragedies are driven by an escalating logic of self-annihilation taken to extremis. In the constellations of American capitalism, they are driven by the nova effect, sound and fury which bursts in a mighty bang. Farces are controlled burns, which end in a whimper.

The tragic dramas of course get all the attention, and perhaps rightly so. PolicyTensor is always quick to argue against those who make availability heuristic observations as departures from cognitive rationality. A form of capitalism which is so bereft of its accounting capacity as to not deter and detect obvious scams, conducted in the open for all to see, clearly possesses a legitimation malady which could become cancerous. SBF plainly told the OddLots hosts, that I am in the Ponzi business, and it has been pretty good to me. Dumbfounded, I remarked to Dominik Leusder that it is the apex of financial nihilism. His reflexive response was revealing, indicating it was definitely the apex of something, potentially still unknown.

I side with Adam Tooze on this debate. While some may detect an inconsistency between let it burn arguments with respect to crypto winter and let it rip with respect to COVID, there is no comparison. Keynes’ first principle to distinguish between the Agenda & non-Agenda looms in these discussions: “the finest task of legislation is to determine what the state ought to take upon itself to direct...and what it ought to leave.” A perfectly rational way to deal with scarcity of attention—a problem that is fundamental and even the best and brightest cannot escape— is to recognize when a threat is potentially systemic in nature, and other activity which is structurally insignificant with respect to global portfolio flows.

Tooze appears to have returned full circle to the hubris of we are deregulators now. But that is a misinterpretation. He certainly does not fall under the rubric of my more precise claim that We are all Jeffersonians Now. The trajectory of a particular kind of investment characterized by temporal ephemerality and spatial fragmentation starts as purely Jeffersonian but proceeds according to a logic which undermines it. Those patterns of investment present in the dot com bubble were taken one degree further under the spell of the crypto/VC craze with the removal of boundaries to notable effect. The world of laissez faire, rational markets, and equilibrium states had been abandoned because a simple biological maxim was no longer observed. For markets to emerge, adapt, and evolve, they have to be alive. If you are not dealing with a commercial entity that follows these principles, they are something else—a zombie who by way of its lack of attachments enables it to transgress boundaries. In the Fordist Age, they were natural boundaries. In our world, they are porous artificial ones and stop-gaps.

The ecological metaphor of a controlled burn does allow for the possibility of regulation, while still observing the Keynesian legacy. Let the fire run its course, and if anything remains in ecosystem other than belief, regulate—and this is the key—while in weakened state rather than let it become invasive, overgrowing ecosystem beyond the scope of regulation. In this respect, the whimpers, not the bangs, are important, because if one fails to direct attention at these junctures, regulators may be dealing with a zombie. That zombie could perversely jeopardize every virtue which drives capitalism forward, and delivers prosperity by way of modulated credit. Keynes would be paying attention.

On the second Tweet of Christmas:

A bit of a confession to followers who do not know me well. I am occasionally drawn to terrible liberal instincts—and that would include my tendencies to follow Doug Henwood down the tight money liberal siren song. Tight money liberal is as much of an oxymoron as political science, and I would suggest for similar reasons. Just say “politics” and avoid the decades long project to make liberal politics smooth and technocratic, a fascination that has gripped certain professional segments since the 20’s if Mattei’s history is to be believed (a Christmas ask for me btw). The past isn’t past. That legacy continues to live on in technopopulism. Put in a pin in this—it deserves a future post when I spend time with Mattei next year.

The transition from populism to technopopulism, the embrace of austerity with a liberal delivery, observed most starkly in Europe from the dominance of French Socialists to Mitterand to Sarkozy and the Italian Communists to Berlusconi to Draghi has my mind drifting to particular moment in American politics, the genesis of the Tea Party, the beginning of my political awareness. I recall my father telling me in long car rides, riffing off the blockbuster hit, The Dark Knight, “You are either a conservative or on your way to becoming a liberal.” In macrofinance debates, I can imagine a similar statement: you must be perfectly on board with the enlightened consensus of the Employ America folks, or you are on your way to endorsing libertarian crank, Tom Hoenig, as a prophet.

I came embarrassingly close to doing just that in my review thread of Christopher Leonard’s book. Extending out the thread on the newsletter, I even resurrected the Enemy of the People concept, to stand in for thinkers and policymakers who were ignored at the time, but later vindicated. I stand by only the core of the claim. The 2010’s interregnum from “respectfully, no” onward was, tragically, an intensification of the “political success, economic failure” pattern of neoliberalism. The devoted political applications of the other authority I regard as an Enemy of the People, Karl Marx, interestingly observed a similar pattern which we might call hypernormalization. Merging those two thinkers was the purpose of constructing a circular thread bookended by Paolo Gerbaudo’s The Great Recoil.

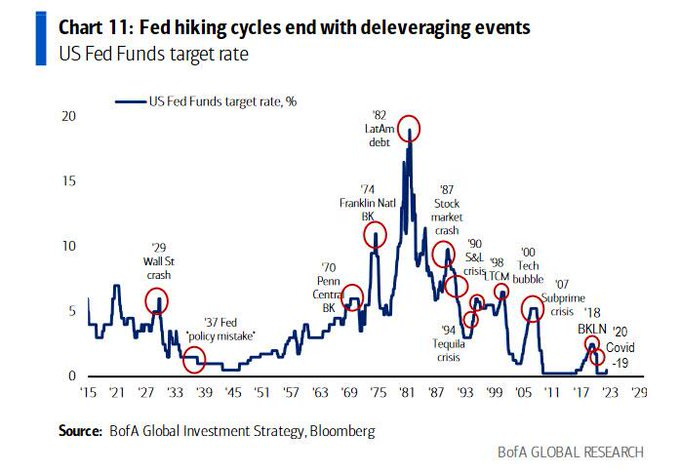

In the end, we can debate whether Leonard wrote a useful, or at least interesting, book until the cows come home. But there is no disagreement on the critical point. In the U.S. and Europe, unforgivable errors were committed in the 2010’s. In the U.S., they relate to the original sin of monetary policy which began 50 years ago, bringing down with it the middle class and every subsequent hike a stratification of the hourglass economy. The blunt instrument of rate hikes is the smoking gun between labor productivity/ wage divergence, a domestic scandal repeated for emphasis in then-Chief Economist Stephen Roach’s reflections on the future of Chimerica post-GFC. The scandal was not without its uses for elites facing down the ungovernability crisis in the shadow of the Trilateral Commission. Just as the Sovietologists of the era would criticize dysfunctional Soviet agricultural policy as “working” if by work you mean to satiate the demands of key constituencies, work means to placate the demands of organized labor. Historian Fritz Bartels’ chapter on the subject is titled, Defeating the Enemy Within. “The enemy” being ordinary citizens seeking security, stability, and autonomy in the workplace. The political success was so total that even economic failure in the form of skyrocketing unemployment claims and shuddered factories in the 1980’s could not keep Tories and Republicans even in spitting distance of their opponents.

On a deeper level, pointing generally in the direction of critical theory’s postmodern capitalism, I wonder why it is that Americans are made to desire policies that they know are deeply harmful. Tight money liberalism is not even the most damaging of such policies. Rampant NIMBYism, which Johnny Harris emphasized in a masterful NYT video commentary, is concentrated in wealthy blue states, receives an order of magnitude more attention in the unheavenly chorus of public-comment translating proportionally into damage. Henwood, I believe, is one of the wisest voices on the postmodern affliction of speculative capitalism on steroids.

I contend that things fell apart in 2005, settling on neither Huxley nor Orwell, but a secret third thing—Philip Dick’s crisis of authenticity. The parlor game of picking out years to structure a Grand Narrative is in some sense nonsense, but the exercise is useful insofar as it spots conjunctural accidents. If my synthesis of this year’s readings is correct I have spotted four: (1) The productivity boom sparked by the ICT revolution began its steady decline, proving Robert Gordon right that it was only temporary. The Greenspan ‘room to move’ doctrine keeping rates looser than historical experience would otherwise indicate was partially revoked, just as housing peaked in August 2005. (2) A modest uptick in the incidence of private equity zombie firms, where Chairman Powell was honing in his craft at Carlyle Group, like these other trends a harbinger for things to come. (3) The NICE—non-inflationary constant expansion— decade had ended as a result of oil shock brought on by China’s acceleration and the surge in Iraq, centrally located in Helen Thompson’s conclusion to Disorder. (4) The beginnings of the zombie financial market, an unconsciously autonomous market, and the Einsteinian connectivity it engendered could allow market actors to act on the millenarian Commodities Future Modernization Act, the monster so carefully examined in MacKenzie’s study on high frequency trading (HFT). And a bonus: where does Yelin Tan, one of the premier experts of Chinese political economy, date the origin of China’s modern state capitalism—2005.

The enlightened consensus led by Skanda Amarnath has an eminently reasonable theory of the case of how to upskill the labor force into the activities that will be needed in the 21st century economy, precisely those that were driven away by the triple crisis of Volcker decomplexification, Clinton neoliberal hype, and the Great Financial Crisis. The crisis of good jobs, as Rodrik so effectively diagnosed. The prescription is still in development, but the proof concept is 1979 in reverse. That ambition is a bit like uncracking an egg. You can rely on the Trump mode of governance, pretending words alone are sufficient—Tan calls it “directive”— but that is entirely different from actually summoning the capacity for action—developmental. And developmental states3 succeed in precisely the place where thought leaders in LME’s project their fantasies in the capacity to place financial metamarkets back in Pandora’s Box.

Outside of those very special circumstances that gave rise to those states, the systemic vulnerability of the Cold War in Asia, epic head-on collisions are rarely the way to go. Financial nihilism is in fact at an apex, not as a result of regulatory policy but by transformative developments in the world beyond their reach. The Russian invasion on February 22nd made the first six weeks of 2022 seem like an extended 2021 with its attendant emphasis on engineering a 1979 in reverse seem quaint. All of the sudden, the Time to Start Thinking demands could gain a hearing and even the solution didn’t seem like a high-wire balancing act. The structure of feeling is the vibe shift back to stuff.

Indeed, a different systemic vulnerability presented by the possibility of a unified front of revisionist powers, a no-limits relationship, collapsed the four-fold division of ailing productivity, decadent enterprise, energy prices, and dysfunctional financial markets to competitive discipline. The shift was so dramatic it, tentatively, represents 1956 in reverse, a moment so revolutionary let’s not forget it sparked the imaginations of a generation of statesmen and intellectuals. That is the predictable effect of a Russian leader standing before the world insisting he will bury his neighbor, and by extension, the U.S. and her allies.

In sum, there is nothing like a European land war to tether market participants and political elites, often one and the same, away from the dream world and back to reality. Everything was forever until it was no more. The author of the 1979 in reverse idea, Cedric Durand’s recent work is indicative, titled The End of Financial Hegemony?

On the third Tweet of Christmas:

Dorothy Thompson, of course, was commenting on living in the Age of Extremes brought on by the Polanyian implosion of the 20’s re-integration attempt, stretched between the odious horrors of communism and fascism. Make no mistake we are not at that moment. The commentariat, notably Rana Foroohar, insists that international cooperation can certainly steer clear of the 1930’s if participants commit to modifying the mission of global integration so as to withstand sustainability tests.

These obvious differences aside in an age where the dual threat of mass politics has been thoroughly neutered, I agree with Mona Ali and Pierre Charbonnier in the discussion above that I was moved by the greatest essayist of the 20th century.4 I think of Reinhold Niebuhr on how liberalism contrasts with the sublime madness of the soul: lacking "the spirit of enthusiasm, not to say fanaticism, which is so necessary to move the world out of its beaten tracks. It is too intellectual and too little emotional to be an efficient force in history.”

Whenever I hear erudite interpretations of fascism as a vision of politics as energy, of charisma, I'm intrigued for reasons which relate to technopopulism and cybernetics. The overwhelming tension I feel in the moment is that modern politics, hyperpolitics, is defined by misdirected energy. There is tremendous truth Venkatesh Rao tweeted glibly, that it seems to many of us that a near majority (42%) are generative and energized but in an insane alt-reality. The next two categories according to his arbitrary schema are different expressions of depressive realism, that the burden of interpreting the world as it actually is drains the will to act. The subtitle of Tolentino’s linked New Yorker review on the subject is “the abyss between what we think about and what we actually do.” Those categories are, in turn, some form of long-haul debilitating malaise (23%) and crippling-depressed reality grounded (15%). I think the arbitrary splits are broadly right, and the questions for politics lay in the first three categories. Psychotic murderers, his final slice, are only a vanishingly small percent, significant only insofar as they are sometimes the anointed leaders of the largest slice.

The serious point Rao’s extended commentary raises is it actually the case that the world is too complex to grasp, or are some of us choosing to live in a hyperconnected Einsteinian world that is distorting our thoughts, prohibiting exit from it? The year that he suggests a return to as a fix to this dilemma of attention is revealing—2006.

The self-criticism I have articulated this year is that perhaps my energies are being misdirected in spectacular ways when there are urgent challenges where my attention would be better spent. For instance, my hometown’s unsheltered homeless count is now over 11,000, up from approximately 3,000 pre-pandemic. Those grim statistics cannot be missed when you take a stroll or drive down the street. A record number died while sleeping rough in 2021, doubling from the year prior, and it is all a policy choice. I am forced to acknowledge that I am a political hobbyist. In the words of Congresswoman Perez, the new infusion of the Indivisible wave from the WA-3 race, to date the best thing about Trump, “you can read all the books you want, if you don't know what's happening in your community it's irrelevant."

Like a person I admire in my corner of FinTwit, I find myself asking what would have George Orwell done? I have another intellectual influence who is also a personal hero—Albert Hirschman. Alacevich’s biography (Twitter thread here) reveals that he was younger than I am now when he assisted Jewish refugees escaping Nazi territories. I think both cases—and surely, there are many others, they were called the Greatest Generation for a reason—reveal that Dorothy Thompson’s self-assessment of her own liberalism was misguided. The task before them—and us—is to prove that liberalism is emphatically an efficient force for history. As I argued in my February essay on the difficulty of maintaining the quality of attention when quantity alchemizes all, my feeling is that what is demanded of us is to recognize our own human limits. Perhaps it would clarify to depart from the dramatic setting of the rise of fascism and WWII to one that is more familiar to most of us. What would you do in the slower world of 2006? Do that, and don’t worry about FOMO.

On the fourth Tweet of Christmas:

Various people in my circle have accused Delong’s book as a midwit book of the Jordan Peterson mold. I don’t agree, even if I have not sat down to give it a re-read, thinking about it as coherent whole rather than a story in four parts, ending in 2010’s interregnum on a cliffhanger: (1) The Melding of the Research Lab, Industrial Corporation and Global Integration (2) The Deluge (3) Trente Glorieuses (4) The Neoliberal Turn. The key to imparting coherence into a response is to pick apart Delong’s puzzle—why did liberalism fail? Or more precisely, why did the embedded liberalism compromise of period (3) fail? Why was there a need for a neoliberal turn? There is a technical answer. PolicyTensor pointed me in the direction of two French scholars, Dumenil and Levy, who are well-positioned to provide that answer in Capital Resurgent: The Roots of the Neoliberal Revolution.

But that book remains in my library unread. I would like to speculate that subliminal decision to prioritize other reading is because I am more interested in the philosophical dimensions. I think this is the right intuition. Ben Friedman, perhaps self-promoting his 2005 book, The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth, claims that publishers do Delong a disservice by calling his book an economic history, and indeed, the structure of the analysis points to non-economic events. Friedman elsewhere recited his definition of “moral”, which he recognizes is loaded term that misinterprets his intent to simply call out the institutional trust that underpins market orders. An aim that has never been quite realized except shallowly in the narrow radius of the Copenhagen circle. What Thompson witnessed was the effloresce of a “moral” society in an outpost of that circle in Vienna.

Though, in a certain sense, to describe Vienna as an outpost is exactly backwards. The dramas which played out there drove subsequent history, as indicated by the structure of Delong’s Grand Narrative. In one corner, Polanyi. The market was made for man, not man made for the market. In the other corner, Hayek. The market giveth, the market taketh, blessed be the name of the market.

In the highbrow narratives, there are other lesser known figures who would go onto shape the outlines between the titanic struggles between liberalism and its opponents. They are adroitly covered in the Politics in a New Key: The Austrian Trio chapter of Schorske’s classic. If it can be said that most people form their political intuitions in the Harvard yard when they are ~25, Delong’s puzzlement relates to his strikingly similar position in America discourse as his befuddled Austrian predecessors. Liberals, when they exit their offices into the center of Red Vienna or down Telegraph Avenue, inevitably encounter Social Democrats who sometimes call themselves socialists, and vice versa. They operate according to the heuristic that any departure from “white bread” proposals is always good for working people. Against the relentless class war of Gilded Age political economy, those proposals are not irrational only unreasonable.

The creatures that are less recognizable to Delong are those who were bred within elite institutions and even started off as political liberals, notably Viktor Orban, Ron Desantis, and Donald Trump. They were busy collecting the fragments left behind when narratives of progress— “forward” and “backward”—and hierarchy—”above” and “below”—no longer retain their authority. They were political entrepreneurs who could “grasp the socio-political reality” the liberals sense of boundaries could not imagine, Schorske writes.

No history of protest movements, Gal Beckerman recognized in his chapter on the Italian Futurists, is complete without these “primitive” characters. Primitive has a double meaning. They were the first, triggering an accumulation of mass politics. They were also intimately attuned to the preference for the primitive. Whether they are playing a Keynesian beauty contest vis-a-vis public opinion5, an entrepreneurial art which doubles as epic conmanship is up to interpretation. But a con performed with authenticity carries with it tension that highlights a comparative advantage relative to liberals. Forced into a salvage position as counter-elites, often within the deviant streams of globalization, cons are trained in the arts of noticing for the same reasons as Tsing’s mushroom pickers. Noticing is a matter of survival.

The Austrian trio gives rise to two opposing potential reactions, the artist’s dichotomy between Pablo Picasso and Paul Klee. The broad arc of artistic expression in the 20th century Gombrich describes so as to encompass both regression and refinement is of broader interest than to art historians for the same reasons the strategies promoted by Schorske’s trio of politics by other means, combining explosively with “the wider cultural revolution”. Expression to encompass both regression and refinement, you say? Does that not describe hyperpolitics in the social media age?

The dualism between these stylistic tendencies is not perfect but present. That would be broadly between a precociously divine inspiration uncovering a deeper reality that cannot be observed, only guided by professional discursive training, and simply noticing that which is there by synthesizing fragments. Picasso was ironically a permanent resident of Model Land, “I would like to know if anyone has ever seen a natural work of art. Nature and art, being two different things, cannot be the same thing. Through art we express our conception of what nature is not.” Paul Klee possessed the humility of knowing when to periodically make the escape, Gombrich writes, “the more gentle explorer…he indeed made good his intentions of learning from the art of children, without ever becoming childish. The more you prefer the primitive, the less you can become primitive.”

For those us who occasionally feel inclined to pick up a book with a foreign title, like Fin de Siecle Vienna, or read Noema articles on the philosophy of insects, there is a lesson here. The people have spoken and they like 6’ 8” big bois in the mold of John Fetterman. For similar reasons, “second-class intellects” like FDR and Joe Biden have a tendency to be historically transformative. Say what you want about Biden`s meme persona, but 2022 headlines that he “failed” have a Dewey beats Truman kind of feel to them. Notwithstanding my personal adoration for Jimmy Carter, give me each of those second-class intellects over Carter and Obama every day of the week. Politics is an exploration of noticing the opportunities which are there—Kleeism— not the genius of summoning those that do not exist—Picassoism.

On the fifth Tweet of Christmas:

“Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive,” Howard Thurman.

I think I may have had a singular experience reading Delong’s book with “Something in the Way” by Nirvana ringing in my ears after finishing The Batman. What is the something that is in the way? Economics, sure. Like the UCSD professor of social democracy who left a deep impression when I attended by recommending Ben Friedman’s first book, I am broadly in agreement that there are moral consequences to economic growth. And to give a spotlight to a recent discussion between two brilliant economic historians, Tim Barker and Yakov Feygin, the key subpoint about those moral consequences is they vary substantially in the event of protracted slowdown and actual stagnation. In an alternate reality where Obama did not screw up so royally (alternative reading: if Clinton saw the threat from right-neoliberals more clearly before Tea Party gained steam, emasculating fiscal policy and ensuring self-incurred immaturity), Feygin imagined they would both be suburban Republicans right now. We would be living the Dream, one that is embedded deeply in the Greek principle of Oikonomia, practically expressed in American history by limitless outward expansion, and still observed in housing regulation of cities like Houston. A prominent critical theorist once said that a person who wants something that is not offered by the world becomes a revolutionary to obtain it. Critically, what drives forward that revolutionary activity is an awareness that good thing existing initially in vanguard’s imagination will be made available to others who do not yet realize they also desire it. Barker and Feygin are the vanguard; I’m the laggard.

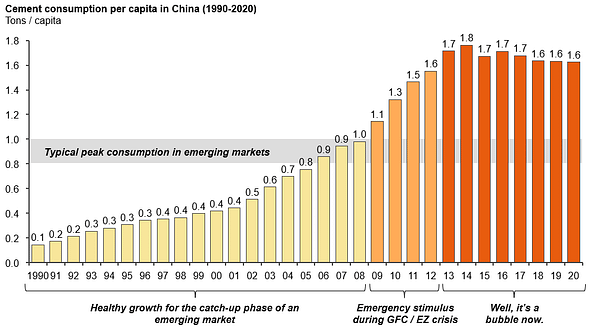

In the U.S., the hysteresis effects—Greek for “that which comes later”—of the GFC was protracted slowdown. In some parts of Europe, elites chose to inflict actual stagnation, destroying the life chances of millions of young people. In China, front and center of Friedman’s current reflections, the question of slowdown or stagnation. A related question, did China’s zero-COVID posture mean that it crossed the Hausmann barrier of negative growth often observed when a rapidly converging country settles on new growth path, is of world-historic significance. It’s an inexact science, relating primarily to the uncertainties of national accounts, but a country that navigates the transition smoothly makes a slowdown scenario more likely, while countries that alter growth paths traumatically are more likely to fall victim to the stagnation scenario. The difference is between Argentina and Poland. An Argentinian, Brazilian, or, as Rozelle warns Chinese education ministries, Mexican growth episode would trigger a reverse alchemy, where the reinforcing logic of integration generating social harmony, international openness, and mutual respect is turned against itself. Degrowth is idiocy for all except the disaster capitalists who profit as merchants of hate.

The fundamental question, in other words, is of ethics. I wrote that morally, the sophisticated networks of exchange are stuck in the Speedhamland system, perturbed by what the working class might do with leisure. They might decide they like the freedom leisure offers, and want more of it. Being an ostensibly free society, propaganda is devised to misdirect consumers into a cacophony of competing conceptions of freedom, except for the real thing. The opening lines of David Hume’s treatise on government are instructive, “Nothing appears more surprising to those who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye than the easiness…with which men resign their own sentiments and passions to those of their rulers.”

The Bloomsbury clique, represented in a pair of essays by John Maynard Keynes and Bertrand Russell, offered a way out from this descent which envelopes all, should technological progress deliver. Envelopes all is an important addition. As men resign their passions to more abstract conceptions of rule, principally modern accounting, but also Big Data automation and possibly AI, the implicit consent of the governed from the many to the actively governing few grow ever larger and smaller. Keynes and Russell, while no Marxists, wouldn’t have been out of step with the sentiment expressed by David Harvey to resist the economy as an abstraction.

Just as Hume was engaged in determining “the first principles of government”, Keynes and Russell were engaged in the first principles of human flourishing, primarily a willingness to engage in the difficult work of drilling down the sentiments and passions of the people. That work is impossible if it is conducted solely by a mandarin clique, trying to make society legible to their esoteria. The working class must be an active co-participant in bringing those passions into being.6 In this respect, democratizing the highest goods, like spending the afternoon in your best chair allowing your thoughts to wander, does not debase them, but enhances the possibility for human flourishing.

Technological progress delivered in precisely the way Keynes outlined and Russell hoped, and yet the transformations are not as deep as conceived. There exists some deep anthropological belief, predating even Speedhamland and suggested by Graeber, that doubts this fact. That is the something in the way. “The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently,” David Graeber.

Not coincidentally, the late David Graeber was, I’d argue, one of the world’s leading thinkers on bureaucracy. Walter Lippmann emphasizes the connection in a passage titled Routineer and Inventor from a treatise operating in the lineage of Hume, A Preface to Politics,

“Now there are days—I suspect the vast majority of them in most of our lives—when we grind out the thing that is stamped upon us…then because our days are so unutterably the same, we turn to the newspapers, we go to the magazines and read only the "stuff with punch," we seek out a "show" and drive serious playwrights into the poorhouse. ‘You can go through contemporary life,’ writes Wells, ‘fudging and evading, indulging and slacking, never really hungry nor frightened nor passionately stirred, your highest moment a mere sentimental orgasm, and your first real contact with primary and elementary necessities the sweat of your death-bed’…The world grinds on: we are a fly on the wheel. That sense of an impersonal machine going on with endless reiteration…most of us hide our cowardly submission to monotony under some word like duty, loyalty, conscience.”

The question that British filmmaker Adam Curtis explores in his films is it still possible to summon those passions which make us feel alive—not that which is disguised in the language of duty to feign belief in a system the world has long since abandoned. That is the million dollar question because there is no future unless we create it. Utopia is for walking. Delong knows this to be true through the operative metaphor of slouching to a singularity of his Star Trek sensibilities. So did Lippmann, anticipating Keynes’ jam tomorrow and jam yesterday, but never jam today?

"[Some] put Paradise before them rather than in front of them. They are going to be so rich, so great, and so happy some day...They didn't fall from Heaven..but they are going to Heaven with the radicals...whole fine dream is detached from the present," Lippmann in Drift and Mastery.

On the sixth Tweet of Christmas:

I noticed that I was reflecting on Delong’s book, I found myself thinking about two thinkers who visited Peking University in 2018 when I attended, Robert Putnam and Joel Migdal. Others have been thinking deeply about Putnam’s work as the post-industrial world faces the most severe loneliness epidemic in history. Even positive indicators like rapidly declining Gen-Z drug and alcohol consumption are not quite as they seem. Sociality, the German philosopher Harmut Rosa reminds us, costs money. What is money if nothing more than the promise that it can expand your life experiences, Rosa proposes?

In a similar vein, Dominik Leusder channeled Jager’s analysis by suggesting that the decreased propensity for heavy drinking is a nested function driven by permanently lower disposable incomes. Social activity costs real money, but the two forms of metaverses, online and getting high, require more modest sums. If the theory of the case is correct, reversing the second Gilded Age is a chicken in the egg problem. To counter ailing investment, policymakers need to engineer higher disposable incomes within non-elite segments of the public, but it is difficult to see how that can be done without drawing from remaining institutions in public life which provide sociality to those privileged enough to access them. Universities, one engine of upward mobility, are great but they do not operate at the scale required and are facing an affordability crisis. These puzzles are what I had in mind when I wrote in the context of Britain that determinants of restoring growth are irreducibly social.

Just as the 90’s promise of the internet to expand real social connections were tragically betrayed, the explosion of bits of information aggravate rather than alleviate attempts to congeal into a public narrative. We need rituals to co-create a common meaning, the most interesting philosopher I’ve never heard of argued in a Noema interview. I have a few criticisms that are surely related to my Truman Show experience on social media. To me, it would appear that the regularity in which everyone in my circle goes to the little blue bird app to get a stream of notifications from individuals proven to provide dopamine with their insight is a kind of ritual to create common understanding. An ersatz form, to be sure, but the fact that we have found each other at all across several times zones, disciplines, and social strata, and managed to hermetically seal ourselves from the nastiness outside, is worth preserving. Dominik Leusder articulated the best defense of that live mission, challenged by one wild oligarch’s vanity project. After we have already done the difficult work of finding the others, forging an incipient community, we would be foolish to turn our back on it.

On the other hand, I am forced to acknowledge that there is perhaps not a single topic in the modern world where Tsing does not resonate. The unravelling of the public has forced us into these novel media, enabled by digital technologies, which might even appeal as we navigate amidst ruins. But they don’t scale. Perhaps some of us are doing it, in the spirit of Tsing, as a deliberate decision to avoid scale as distorting clear thinking. Insight can often come from that kind of orientation away from mass culture.

At some point, however, shouldn’t we acknowledge the ruins that surround us? Wouldn’t most people prefer more structured forms of ordering the information environment #supportlocaljournalism, in which they are simply stuck in a classic prisoner’s dilemma? I remember standing up during a Joel Migdal lecture in March 2019 on his book project, Who then will speak for the common good?, contextualizing Barbara Jordan’s bicentennial prophecy. Isn’t it strange that you appear to be expressing a nostalgia for the absurdly high barriers Gilded Age WASP’s placed on entry to generate order through boundaries of exception, when you yourself acknowledged that you are a beneficiary of the first wave to diversify the academy away from this insularity, incorporating Jewish-American voices into the national story?

Summarizing my recollection of his response, which to be clear is different from his actual response, he told me there has to be a way to split the difference, in the language of Charles Maier, to reform stability without revering it. In other words, he was contemporaneously engaged in similar work as the historian, Jill Lepore, toward a New Americanism. That call to action to revitalize the American public is worthy of attention, if, here too, I’m skeptical it will scale. There is a more fundamental barrier to be resolved, the subject of my next tweet.

On the seventh Tweet of Christmas:

(Note: Above tweet reacting to Nikhil Pal Singh— “the truth laid bare— to control worker time”)

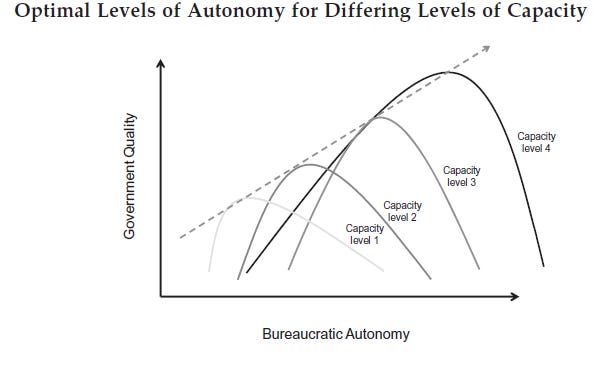

At various points in the commentary I have noted that discipline is Janus-faced. On the one hand, it certainly drives forward the process of modernization for the 10,000 neoliberal orders seeking to climb the ladder of causality from the moderately prosperous xiaokang society of association to the highest imaginative stage. On the other hand, the rules required to make the ascent have a restraining effect once attained. Fukuyama calls it vetocracy. In the chapters reviewing the literature on organizational capacity, Fukuyama’s second volume writes that managing a McDonalds differs fundamentally from managing Google.

Tyler Cowen makes a similar point in his book, Talent, by citing Wittgenstein, development is to know when to kick away the ladder of rules. Organizations observe a similar pattern of reflexivity, where the rules which enabled their rise also give way to sclerosis, profiled in Chris Miller’s historical overview of the semiconductor industry, Chip War. A quote from the IBM President and namesake for world’s most famous supercomputer, Thomas Watson, is worth remembering for believers in the overshoot, to run labor markets intentionally tight to upskill the economy. “If you want to increase your success rate, double your failure rate”:

I confess that I have never thought of the connection between Rostowian maturity as an exercise in time discipline before. But a Yale historian, Vanessa Ogle, has in The Global Transformation of Time 1870-1950. The overlap with Delong’s long 20th century is intriguing. If Ogle’s narrative is to be believed, the locus of the 1870 transformation is not regularizing the process of investment—allowing the Routineers to be routineers and the Inventors inventors, but the attractive power of brutal time discipline for Third World modernizing elites:

Time or the absence thereof, thus became a measure for comparing different levels of evolution, historical development, and positionality on a global scale. In the second half of the nineteenth century, workers, and employers alike struggled over the meaning and division of social time, of wok time and leisure, and the appropriate proportion between them…Foucault’s ‘complete’ institutions…[globality] of 19th century globalization was classifications among individuals, collectives, and their functionally differentiated times…non-Westerners were collectively indicated as work-shy and incapable of proper time management. In a world of imperial competition, were internalized by reformers…who stood at risk of succumbing to Western superiority…[catch-up] reflected a 19th century preoccupation with progress and modernity which was built on similar notions of linear historical and naturalized evolutionary time…The aspiration to be modern so captivating to scores and intellectuals and reformers beyond Europe and North America became another tool for global positioning.”

The takeoff can be said to have occurred when collectives make the transition away from spending every waking second searching for a buck in urban informal sector or tilling fields which can be turned into bucks to a society that is made pliant to sunrise-sunset rhythms of the factory floor. The bargain is Pareto efficient. Modernizing elites find the formula attractive for the transformational effect, and their subjects are made no less worse off because they are willing to accept the second kind of time as a lesser tyranny. But that does not guaranteed that all societies are willing to enter the bargain. The strength of the preference is fundamentally different on each side of the elite subject-peasant object relation. Notably, Reform era Chinese elites, speaking the language of pareto efficiency, were the group entrusted with imposing time discipline over the counterfactual coalition of large population candidates, including India, Indonesia, Brazil, and Mexico.

Time discipline is a story that can be said to occur in pareto-maximizing curves. Imagine a society where endowment of time discipline is initially lacking—South Korea in 1960, then imposed so shifts within the curve to the efficient allocation. Realizing manufacturing capabilities with newly pliant peasantry moves the curve outward, which alters the tradeoff between time discipline and creativity. The balance is initially only upset marginally, requiring a few more engineering advanced degrees who are largely contained in pockets which are strategically nurtured. Which is why we should not overstate the depth of the transformation during the Quiet Revolution phase. Governance is still very much operating in the tradition of Mencius, “without rules, nothing can be done.”

At approximately this stage, South Korea led the most successful education campaign in history, birthing a form of modernity that is sui generis to the point that it disorients the Londoner, Perry Anderson reflected after his visit in 1996. He continues, the retrospective success of developmental philosophy revealed “full of potential energies waiting to be released.” The question is how to release those potential energies when the balance is upset more decisively. The nature of the curves that I imagine deep in Model Land is the misalignment of discipline/creativity exacerbated by—and unnoticed as a result of— violent shifts in the curve. The country fortunate enough to have the vanguard of production simply dismisses any Great Rebalancing as unnecessary. They still out-produce their peer nations, to say nothing of the Third World, though not as much as they would under the optimal endowment if willing to exit self-incurred immaturity.

The essence of the overshoot remains to close the above gap. There are two further things to note about the interpretation of the schematic chart. First, the chart implies reaching the optimal endowment technological progress allows will require more time discipline but of a different kind. I propose the extraordinary commitment is like the subsistence farmer, spending every waking second to survive, except the efforts of this manic state are directed to upper rungs of Maslow’s hierarchy. Second, the movements of the curve clarify what it is meant by Tsing, “The problem is progress stopped making sense. More and more of us looked one day and realized that the emperor had no clothes. It is in this dilemma that new tools for noticing seem so important.” During the first phase of modernity, the social determinants of capacity moved in lockstep with exogenous technological shocks, together constituting “progress”. In the decadent phase, technological advance is still with us. We would be hermits not to spot the signs. Still, the deeper noticing is all the elements for that technological advance to be subjectively felt are lacking. Insular vanguardism is the condition that afflicts advanced societies that can grow the pie, but cannot taste it because too much time from too many workers is spent as routineers when I believe their capacities for invention are waiting to be released.

On the eighth Tweet of Christmas:

Note my Twitter feed requires a fact checker. I misremembered the source of the above quote, which is actually Robert Frost. I already referenced this idea in my first commentary in relation to macroprudential regulation, so allow me to entertain the political dimensions.

This podcast was my favorite interview of the year because it features my blast from the past, the podcaster I obsessively listened to during my undergrad days, and my current fling, the one and only Adam Tooze. I was so moved by the discussion because I think it underscores my own intellectual development. A student of polarization and the bonfire of narratives, Klein entertains the skepticism that the march up the escalator depicted by the double arrow in the previous chart, with requisite escalation of the demands of attention to grapple with complexity, is unsustainable. Let's explore the exit offered by immoderate greatness. In this respect, his intuition is connected both to the evolution of American liberalism under Biden, discussed in Tweet #4, and Rao’s suggestion that we ought to reclaim our attention by slowing down our thoughts by returning to the world of 05-06. Ezra frequently reflects on the podcast what would be doing when he started off as a Politics correspondent in 2005, arriving in Washington to build the Paradise Lost of the now defunct blogosphere.

Perhaps inspired by Hirschman’s famous triad, Tooze instructed Klein that he is in fact entertaining a fantasy. The intent of my claim We are all Jeffersonians Now is to signal a budding trend that, as complexity intensifies in the coming years, significant chunks of the left will join the right’s fantasies for exit and rediscover the Small is Beautiful abandonment conclusion of management theorist, Charles Perrow. To quote from the most historically significant 3-page memo since Paulson’s related memo to Congress in 2008 as the appointed director of the committee to save the world:

Post-accident remedies for “human error” are usually predicated on obstructing activities that can “cause” accidents. These end-of-the-chain measures do little…likelihood of an identical accident is already extraordinarily low because the pattern of latent failures changes constantly. Instead of increasing safety, post-accident remedies usually increase the coupling and complexity of the system. This increases the potential number of latent failures and also makes the detection… more difficult. (emphasis mine)

The left must know when it should take its own side, refusing to march with the right down its exit from reality. In terms of signal-response, they are not wholly irrational to behave like a rat overwhelmed by the maze. But, in the uniquely human deliberative sense, sub specie aeternitatis, they fail to understand that their refusal to live by their liberal faith of voice cedes ground to the right. To be sure, the competition is unfair because the right has entropy and other forces of decay on its side. I have already taken the liberty to revise my favorite Batman lines in this post, so here is one more via John Stuart Mill, “Bad men need nothing more to compass their ends than that good men should look on and do nothing.”

Another management theorist, Karl Weick, is more on point, dissecting Tooze’s point of precarious wager. The situation is surely precarious, but it is precisely that precarity which demands a wager, writing in The Impermanent Organization:

Atlan’s poetic depiction is not that far removed from more recent poetic descriptions that summarize complexity theory. Christopher Langton, in the discussing ‘the edge of chaos’ remarks that: ‘right in between the two extremes of (order and chaos) at a kind of abstract phase transition called ‘the edge of chaos,’ you find complexity, a class of behaviors in which the components of the system never quite lock into place yet never quite dissolve into turbulence either.’ Organizing carves out transient order in the space between smoke and crystal. Or stated more compactly, permanence is fabricated. It is fabricated out of streaming experience.”

All that is solid melts into the air, but, as Marx foreshadowed, not by the classic phase transition metaphor familiar to everyday experience, but the unfamiliar quantum realm where both order and chaos exist simultaneously. Get used to the edge of chaos motifs in future installments of the polycrisis series.

On the ninth Tweet of Christmas:

I remarked a few days ago that I often write poor imitations of the essays I would like to read in order to nudge the authorities who are better positioned to write the essay. I know I periodically command the attention of some in the polycrisis space who started in physics, and would like to reiterate that my wanderings on this blog are always an open invitation to share more refined thoughts.

Just as Keynes was the prophet of my 2021 essay, Deleuze is my authority for choice for 2022. To demonstrate, I will simply repeat verbatim an idea that echoes the foregoing commentary, “It is not the slumber of reason that engenders monsters, but vigilant and insomniac rationality.”

And one more to put on deck the ideas that will structure the remaining commentary on the future of Chimerica:

The flow of capital produces an immense channel, a quantification of power with immediate "quanta," where each person profits from the passage of the money flow in his or her own way… There is no universal capitalism, there is no capitalism in itself; capitalism is at the crossroads of all kinds of formations, it is neocapitalism by nature. It invents its eastern face and western face, and reshapes them both—all for the worst…The important point is that the root-tree [of the West] and canal-rhizome [of the East] are not two opposed models: the first operates as a transcendent model and tracing, even if it engenders its own escapes; the second operates as an immanent process that overturns the model and outlines a map… It is a question of a model that is perpetually in construction or collapsing, and of a process that is perpetually prolonging itself, breaking off and starting up again.

An intriguing intellectual pattern is that prophets frequently recur as foils, oppositional forces that thematically meet, whether Tooze or Noah Smith or Pythagoras or Heraclitus. I would like to propose that in this idea of perpetually breaking up, Deleuze is channeling the premise of an asymetrically composed theorist, somebody who is often accused of conflating linearity of logic for thinking, Walt Rostow. He articulated in his opus, a non-Marxian philosophy produced in the passion of the Cold War, “The path to maturity had within it not the seeds of its undoing— for this analysis is neither Marxist nor Hegelian—but the seeds of its own modification…maturity is a dangerous time as well as one that offers new, promising choices.” I am perhaps missing the nuance, but I hear the same idea of quantum indeterminacy stated differently, an interpretation that is surely lost in translation across the Anglophone/Francophone intellectual divide.

On the tenth Tweet of Christmas:

I am losing steam, and responding properly to a series of excellent essays pushing back on deglobalization narratives cautioning with data requires a standalone essay. Nonetheless, I want to jot down a few preliminary thoughts and data points in preparation for two books, which I am really looking forward to in 2023, the Age of Interconnection (1945- 01) and Superstates: Empires in the 21st Century. I will assign some priority to get through my Christmas stack and backlog before their publication dates because I am so enthusiastic about each of those reads. I am curious about Roberts’ to fill in the cosmology side of the physics metaphors for the rebirth of civilizational states in the modern world. And Sperber’s book piqued my interest because of his choice to end narrative with the conjunctural accident of 2001. This point is also emphasized in Rana Foroohar’s Homecoming with the prominent references to Barry Lynn’s 2002 Harper’s article, Unmade. This year’s Noema article similarly notes that right from the start following China’s ascension to the WTO something was rotten in the state of Chimerica. Other more critical voices push back even harder, including Foroohar, revolve their narratives around the very beginning, the arch. That postwar historiography over the neoliberal revolution is increasingly accepted by very careful professionals like Jonathan Levy.

My toe dip into the heart of the trading system, riffing off Russell Napier’s essential account, points in the direction of the late 90’s and early aughts. But who am I to tell those who have undertaken the effort required to descend into the Grothendieckian madness of the heart of the heart that returning to the original mission, Bretton Woods 1.0, is wrong? I will be paying close attention to see if Sperber simply recites the tragic view, dominated by Pettis and echoed by Napier, in excruciating detail or does he use the 800 pages allowed to him to hint at these nuances of the comedic view? I favor the laughing philosophers over the weeping ones, who interpret history through a traumatic lens, for reasons implied by Napier’s epigraph of the Aeneid. The standard tragic view might be grounded in living memory and therefore more elegant and useful to practitioners, but only philosophies that enable the student to look at the same object and see understanding rather than trauma engender learning.

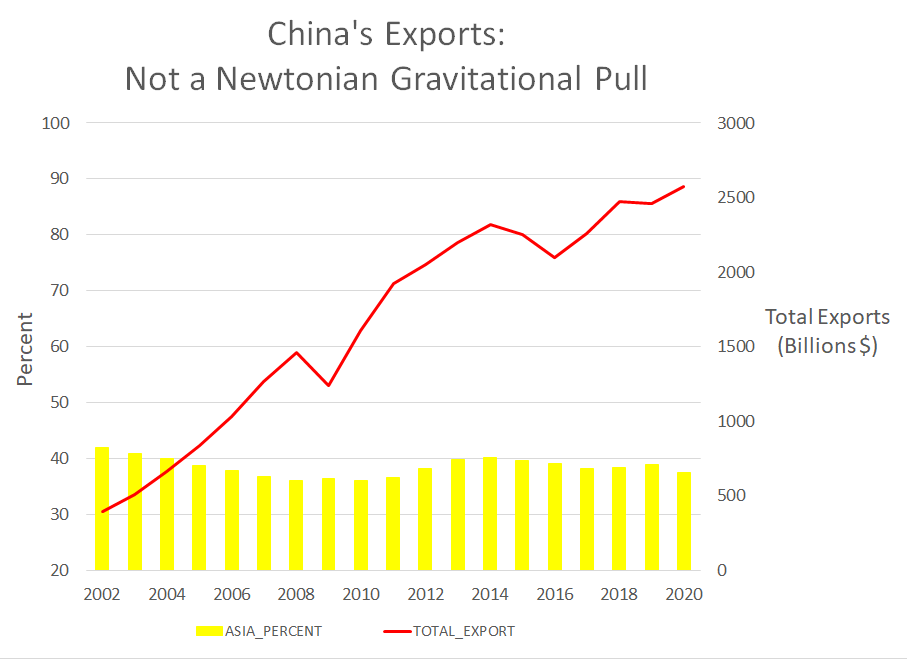

Adding to this chorus, synchronously shouting what deglobalization?, I’d like to commence with another chartbook exercise, analyzing China’s gravity in Asia. For the narrative reasons listed above, 2002 seems to be a perfect year to start the exercise. And I think the exercise, like my previous efforts to examine the expansion of product spaces in Uganda and Bangladesh lends itself to splitting it up into two distinct phases, Defying Gravity (2002-13) and the Return of Gravity (2014-2020). The logic of those markers is to avoid bringing shocks into the analysis, principally the Great Financial Crisis and the stock market crash of 15-16. Richard Baldwin’s period breaks of the global G7/I6 transformations are in a similar spirit, with the return of frictions smack in the middle of the significant shocks cited in popular discourse, the GFC of 2008 and the Trump administration’s trade war in 2018. My periodization exercise will provide additional observations supporting 2013 as a hinge with respect to largest country of the I6, China.

Given my interest in the 10,000 neoliberal orders, the pluralizing gravitational forces in Asia, let’s start with a simple observation from an old book recommended to me by PolicyTensor, Eclipse: Living in the Shadow of China’s Economic Dominance. The book falls into the category of Friedman’s book mentioned earlier, advancing an influential core thesis, which has sections that are very dated.7 For my purposes, the thesis is this:

One of the implications of the gravity model is that trade between two dynamic countries will grow exponentially faster than trade between two less dynamic ones because trade benefits from the gravity exerted by the income of both countries. This is reflected …in the share of intra-Asian trade…not only will the world’s economic center of gravity shift to Asia, so too will the center of trade, with China as the focal point…With China…projected to become the overwhelming largest trader by a factor of 3 over its nearest competitor by 2030. (emphasis mine)

I think of Azheem Azhar on the opposing dangers of forecasting for exponentiality. On the one hand, the naïve person reliably underestimates the power of exponentiality because mathematics is not innate. They have never entered Model Land, nor do they have any desire to visit. On the other hand, certain wired professionals, like Kurzweil or Subramanian, just as predictably overestimate the potential of exponentiality because they live in Model Land. A caveat is that Subramanian ran his provocative forecast over two decades from 2010. It’s obviously entirely consistent for phenomena with exponential properties to appear wildly off at midpoints and to rapidly converge with expectation as it approaches the endpoint.8 However, given that Subramanian has conceded that the assumptions of Chinese dynamism have not held since 2020, unexpected outcome convergence appears unlikely. The unintentional connation of “eclipse”, Yasheng Huang recalled to me was his assessment of the book even prior to Xi, is more on the horizon. You really have to squint to detect any kind of gravitational bloc with China as a hub over the period of analysis:

In fact, during the defying gravity period from 2002-13 of miraculous growth in volumes, the Asia export share was declining absolutely. The volumes were obviously transformational, only upset minorly by the blip of the GFC, to rapidly rebound. More significantly for China’s ascent, the structure of production shifted decisively to top industrial classification codes. Subramanian’s gamble was that IP in moderation works and that it would not jeopardized by the other factors he acknowledged but underweighted in his 2011 book, politics, prices, and people:

The defy gravity period signaled a herculean achievement. A proportional donut chart that was invisible in 2002 all of sudden appeared on the map, and tragically in the Age of the Antropocene, in a span of just a few years. The volumes were dramatic, but the shifts were roughly constant.

And yet, the careful observer could spot harbingers for gravity’s return. China’s exports to Taiwan in 2013 stood at a paltry 5 percent which was almost perfectly matched by China’s already insatiable demand for integrated circuits:

Gravity can be said to have decisively returned in 2013-14 for a number of reasons, chiefly domestic. One of the sharpest management consultants on FinTwit, who appears to pour energies significantly into China’s real estate sector, Joe l'Arsouille has a great thread with a chart detecting when Spanish-level overcapacity became something else entirely.

Another Hong Kong-based financial forecaster, who demonstrated in an interview with Jeremy Goldkorn a trademarked knack for simplicity, highlighted 2014 for similar reasons relating to the property market. While on track during Hu’s second term, those nascent transformations should not be sold as the main event along the broad trajectory of China’s embrace of state capitalism. The authority on the subject, PIE’s Nicolas Lardy, writes in The State Strikes Back that statistics representing a turn toward the state were nothing short of “astounding”:

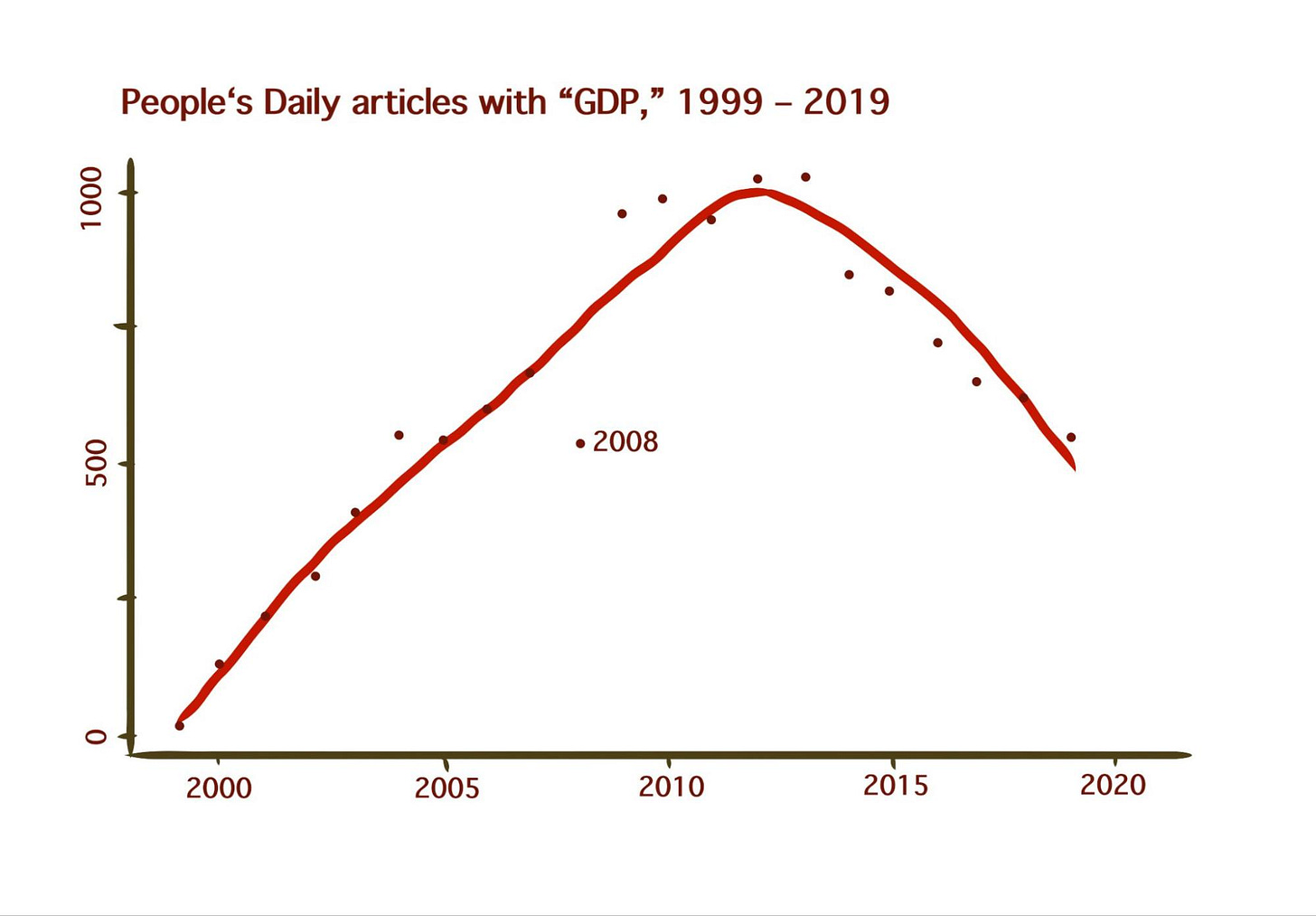

The global reverberations of those Party-state transformations, coupled with the gravity-defying growth in the Chinese economy, left a deep enough imprint that China’s credit impulse had significant effects in recurring waves on global economic activity beginning in 2014. The clever identification strategy employed by that paper to correct the implausibly smooth data, underreporting the 15-16 financial crisis and not registering the 2018 manufacturing slump at all, highlights another issue that is the subject of Jeremy Wallace’s book, Seeking Truth, Hiding Facts. The limited, quantified vision peaked in 2014 when leadership doubled down on New Developmentalism, which began under Hu (recall Tan on 2005), asserting China had grown its way out of the unique transformational epoch, the Rostowian takeoff. All of the sudden, leadership required a theory of public value to mediate disputes. Wallace suggests that the Xi Jinping theory of public value rests not on criticizing the quantified part as crude reductions of complexity, but on the limited part, and that collective mind of digital tech can automate adjudication. The forward to Thousand Plateaus may be indicative of the ambitions for what Foroohar calls the Big State, quoting Wilhelm von Humboldt:

‘spiritual and moral training of the nation derives everything from an original principle (truth) relates everything to an ideal (justice), and unifies this principle and this ideal in a single Idea" (the State)., a fully legitimated subject of knowledge and society’—each mind an analogously organized mini-State morally unified in the supermind of the State. Prussian mind-meld.” (italics mine)

So the causes of the gravity's return, which foreshadowed the reduced growth path, are largely domestic in nature, and relate to monumental error in the politics side of the balance sheet tabulated by Subramanian, and to a lesser extent on the prices side. In this respect, Foroohar’s inclusion of China in a review of broken BRICS, a trend that seemed absurd when emerging markets surpassed their developed peers in 2006, was plausible for her final TIME column in 2014. Though, the call was proven correct due to factors MorganStanley chief economist Sharma outlined.

Read that Foroohar column. As an aside, my favorite “predictions” are simply stating that which has already happened but which is not treated as attentionally significant to all except particular epistemic communities. China’s turn to the state when official announcements proclaimed deepening of the market is one case. International political economist Benjamin Cohen provides another, noting the British school’s predictions were really more indictments of their American counterparts, who suffered from a grave case of myopia. Few would doubt that myopia holds just as well with respect to Ukraine from 2014-2022, which is why Mearsheimer had a moment this year. Sharma has been similarly vindicated, taking a victory lap in the FT for that view articulated nearly a decade ago, insisting eclipse will not come on anywhere close to Subramanian’s timeline, and may never.

Predictions of emerging stars are a tricky business. It is almost as if the selection of particular star causes them to falter. Yet the emerging story is still far from over. As Martin Wolf argued and Dominik Leusder stated plainly on the Eurotrash podcast, “it is not about deglobalization, its about reshifting, and which EM’s stand to benefit from reshifting.” In contrast with the defying gravity phase, the reshifting has been dramatic to the point that “the rest” is, for the first time in the history of China’s rise and modern history of the global trading nonsystem, a sizeable contingent (1/3). They exert their own gravity.

The Vietnam slice, in particular, seems to me to be a particularly dramatic transformation. Something I implied by attaching a street scene from my grandparent’s trip to Taiwan is that an observer on the ground can ascertain the degree of modernity simply by being dropped in at eye level. One of the things the YouTube algorithm knows about me is I like observing street scenes through time for this reason. By that standard, Vietnam is long past the takeoff phase, and at decision phase similar to China when I first arrived in Shanghai in 2015.

If I had to answer the Fallows question, where is the future being forged, I would select Vietnam. But Taiwan, according to Noah Smith already a “unique civilization” the mainland can only parrot in their propaganda, is a fine answer too. The paradox of neoliberal globalization as efficiency to an absurd degree, if it is ever resolved, will be resolved there.

Recall the thought about Jeffersonism, if it is implemented faithfully, it proceeds according to a logic which undermines its operating principle of stabilizing barriers to credit growth across time and space. The logic is true in reverse for globalization as a mechanism that enhances economic security through open access to the world’s markets. The Econ 101 example is how trade allows small countries to weather localized droughts, leading to sharp drop in food production, compensated for by international trade, which balances out temporally in Model Land. Chris Miller’s money line is that globalization perversely produced Taiwanization. I recall macro analyst Lyn Alden writing on Twitter, the only country that is self-sufficient in semiconductors is Taiwan, and Taiwan is not self-sufficient in energy, so Q.E.D no country is self-sufficient. Charts like these, escalating concentration in one core strategic industry, would not be so concerning if the trust that underpinned open access orders was still present. Absent that, many of us are increasingly wondering if the globalization dream deferred, as much as the dream still persists for flying geese laggards like Vietnam, will merely fester, stink, and sag like a heavy load or will it explode?

On the eleventh Tweet of Christmas:

“When considering any philosophy, ask only what are the facts, and the truth the facts bear out, never let yourself be diverted by what you wish to believe or think beneficent social effects if it were believed. But look only and solely— what are the facts?” Bertrand Russell.

A significant difference between this year’s edition of 12 tweets with last year’s is that climate breakdown is only tacked on, not the overwhelming force driving the narrative forward. I mentioned that my aim of this exercise for the coming years is to get a sense of how my internal sense of history was experienced in the moment. This necessarily differs from other’s. Citing Latour on “bias” and “interest”, Tooze told Noah Smith that conceptions of polycrisis are irreducibly perspectival. I confess that I have penchant for catastrophism in analysis, but this essay does not take on that tone for the simple reason that when I turned on the TV in the evenings, it was not to anxiously check if Lake Tahoe burned down by the Caldor Fire. Attention is a strange thing, I remarked in July just as Europe and central China were being rocked to the core by record heatwaves, disrupting electricity loads, economic activity, and even the London Tube, prompted me to record a voiceover of that essay.