The Moments where Decades Happen

An Annotated Reading Guide for Christopher Leonard's The Lords of Easy Money

“There are decades where nothing happens, and moments where decades happen,” Vladimir Lenin.

Last night, I finished reading Christopher Leonard’s fantastic accessible book, The Lords of Easy Money. Leonard came on my radar when I read his Politico profile of the book’s main subject, Thomas Hoenig. With the emphasis on Hoenig, now a fellow at the libertarian-leaning Mercatus Center, you might think this is a book that is only intended for the devout followers of Ron Paul, who have been obsessed with the rallying cry to end the Fed for years. I don’t doubt that these folks and the Bitcoin bros will find plenty of talking points to like in this book. But I would like to propose that Leonard attempted something more ambitious that a larger audience not necessarily interested in arcane details of how the financial system works would also benefit from.

While reading through the book, I recalled my first major research project during my Freshman year of high school assigned to me inspired by a particular reading of Henrik Ibsen’s play, Enemy of the People. The assignment was to pick any figure from history whose activism was summarily dismissed when he was alive, but whose insights and/or warnings later proved prophetic. The philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, summarizes this pattern well, by noting that any path to discovering truth almost invariably passes through three stages, “First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.” In standing up to the FOMC committee during that critical moment in 2010 (“respectfully, no”), Hoenig is arguably a textbook case of Enemy of the People concept, as his hesitation appeared to talking heads and editorial columnists as a sadistic attack against ordinary people still reeling from the bezzle of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. As Leonard notes at the end of the book, while Bernanke’s Courage to Act was celebrated with lucrative speaking events and an appointment at the prestigious Brooking Institute, the price to be paid for Hoenig’s dissent was that he would be excluded to the margins of the profession with the libertarian cranks at the Mercatus Center. If it were not for his book, very few people would even know who he is or what he did at that critical moment in 2010.

There is a deep point here that lone wolves are often the arbiters of enlightened wisdom. By definition, to be great you have to be willing to go out on a limb. For this reason, one of my all-time favorite memos from the legendary value investor, Howard Marks, was titled, “Dare to be Great”. The stoic philosopher, Marcus Aurelius, once emphasized the value of departing from the madness of crowds, “The object in life is… to escape finding oneself among the ranks of the insane.” The broader point is that we like to think of limits to cognitive rationality as contained solely to meme investors captured by GameStop mania, while attributing perfectly enlightened expertise to the folks who have a seat at the FOMC meetings. If Leonard’s interpretation of Hoenig’s philosophy toward bank and credit regulation can be summed up in a single sentence, it is that limits to cognitive rationality are in fact more universal than is implied by a simple division between an enlightened technocracy and the madness of crowds. For all the data we possess to follow the flood of reserves, central bank regulators like the woman at the New York Fed he mentions in the book, Lorie Logan, are still fundamentally operating in the dark. Their ad-hoc crisis management is a predicament familiar to the favored economist of every airport bookstore, Albert Hirschman, “They can’t know, but must try.”

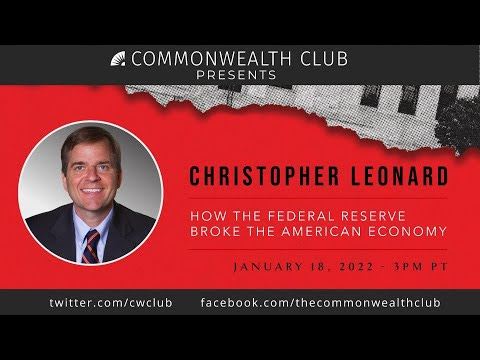

In a Commonwealth Club discussion with Lenny Mendonca, Leonard revealed that the alternative title he proposed to his publisher was The Long Crash. This aligns with Adam Tooze’s masterful accounts of the long decade of financial crisis in Crashed and Shutdown. In each narrative account, 2010 was a turning point1, that opened the door to perpetual crisis management to merely keep the economy humming along. To an outside observer, it may appear that the political scientists, Baumgartner and Jones, who studied the punctuated dynamics of congressional legislation applies in equal measure to financial panics, which as Tooze and Leonard both emphasize has now spread to the bread and butter of the global financial system, the treasury market. Those political scientists noted a Republican lobbyist’s quip that Congress only does two things well “nothing and overreacting”. For all the research capacity the Fed commands, they often fall victim to the same political dynamics because in the end they also lack the ability to synoptically process signal information. Those limits compel them to normalize deviance until pushed up against the precipice and they are compelled to overreact under the mantra of the “courage to act”. Leonard writes that the normalization of deviance occurred in September 2019, which later became more apparent as the economy came to a grinding halt in March 2020, written about in Tooze’s Shutdown. On his Chartbook, Tooze revisited the strange world bond traders encountered last fall, arguably an analogue normalization of deviance period. The ominous question is if the pattern will recur this year, and if so, what will be the trigger?

Now that I have these scattered thoughts out of the way, I thought I would share my notes on the book that can serve as a reading guide to my followers who are also interested in purchasing it. I completed a similar exercise for Paolo Gerbaudo’s The Great Recoil on possible futures of post-neoliberal capitalism. At some point, I will convert my notes for this book into a Twitter thread too.

Context of Fed decision in 2010 (pg. 13)—ominous headlines that the GOP, led by Tea Party insurgents, took the House. That would ensure the emasculation of fiscal policy and that the Fed would be the only game in town, as later argued by monetary policy hawk, Mohamed el Erian. Leonard sets the opening scene for the narrative arc of the rest of the book in the aforementioned conversation with Mendonca:

“Bernanke published papers on this [breaking the zero-lower bound] concept as far back as the early 2000’s” (pg. 23-24). When researching the aftermath of Japan’s everything bubble in the late 1980’s, I suspect that I encountered some of the same Bernanke papers, which are fascinating historical documents:

“Fundamental dysfunctions of the American economy” [e.g. expanding gains from education, investing in R&D noted in Hacker & Pierson’s book, American Amnesia] (pg. 28). This section reminded me of a refrain from an old professor at LSE, David Woodruff, that monetary policy is a blunt instrument. I have been meaning to revisit a law review article on the this theme, titled “The Role of a Central Bank in a Bubble Economy”, reviewing some of the risks that built-up in Japan during the craziest run on asset prices to this day. Miller wrote in the abstract, “Where a bubble becomes so large as to pose a threat the entire economic system, the central bank may appropriately decide to use monetary policy to counteract a bubble, notwithstanding the effects that monetary tightening might have elsewhere in the economy.” However, that is a measure of last resort as “tightening monetary policy was not finely crafted to deal with …the underlying problem (Miller 1075).”

“Permanent hole in the foundation of trust… in 1971” (pg. 41). Last August, I reviewed an important book by a MIT economist, Peter Temin, arguing the insights of the Lewis model are relevant to the U.S. if you rename the terms, low-wage and FTE sector. One interesting point in that book is that the Nixon shock and the Powell memo, remaking American political economy so affluence bred influence were “the coincident events” of 1971. After the fallout of Vietnam, you can add one more thing usually viewed as a more distant consequence of those decisions—the spectacular decline of trust in public institutions.

“Misunderstanding.. ‘cost push’ and ‘demand pull’ inflation” (pg. 61): To those who want a detailed account of both distinction, the trouble with the Philip’s curve proposing a neat tradeoff between inflation and unemployment, and the political economy of inflation, Scharpf’s explanation in 1987 remains an unrivaled resource.

“Monetary policy follows fiscal policy ….[followed by discussion of Roosevelt’s New Deal]” (pg. 78-79): Bernanke’s invocation of Rooseveltian resolve in the article linked above was actually more of a projection, a power he might have desired as Fed Chairman, but did not possess. As has been noted by some perceptive observers, the option of unconstrained monetary policy with constrained fiscal policy most of the world settled on following the Great Recession was a kind of straightjacket as central banks frequently lack the authority to perform the functions usually constituted to democratic governments. This was also Miller’s point on the BOJ, and comes out in the straightjacket Leonard describes following the collaboration between Mnuchin’s Treasury and Powell when they took the unprecedented step to directly purchase private debt. The administrative lines grow increasingly blurry.

“It raised them so slowly that they were still ‘accommodative’” (pg. 93): This was referring to the run-up of the prior housing bubble in 2004, but matches Joseph Wang’s points on terminal rates as the Fed faces its current quandary. He argued, “So far [the Fed’s orientation] hasn’t changed all that much. What we have been doing so far is pulling rate hikes forward. And that’s meaningful, but it is not as impactful as the terminal rate........I think at the minute we are a bit above 2%. That’s probably still too low. I expect the Fed to say things, eventually, so the market can handle it, that it goes to 3% or above. I think that’s when the real damage to risk assets happens.” Discussion below:

“Bernanke was an ‘inflation targeter’, meaning that he…would most likely focus on price inflation rather than asset bubbles” (pg. 93): I suspect that one of Leonard’s primary motivations for the book was to drill down the difference between price and asset inflation. The difference is not commonly appreciated in even business discourse or among Fed economists, and when it is acknowledged it is filtered through this misguided politically-driven notion of “retail inflation bad, [asset]/home price inflation good.” On this basis, Colin Hay argued in 2009 that the default preference for low rates in the UK and Ireland indicated “a covert repolititisation” and therefore perversion of official central bank mandates. I echoed the covert repolitization thesis when engaging with Stefan Eich’s work on the politics of money.

“Unelected Power…democratic institutions were increasingly shifting power to nondemocratic institutions, like the military, the courts, and central banks” (pg. 103): PolicyTensor noted a quote from Michael Lind on how encompassing unelected power has become, “Congress delegates foreign policy to the president, economic policy to the Fed, and social policy to the Court.” In the end, there is no substitute for eyes and ears on the ground, which is why he hits the nail on the head in arguing that the political purpose that ought to animate concerned citizens to is to revive elite-mass relations, reversing the secular trend toward outsourcing essential democratic functions to this nation’s capital under the guise of expertise. The tension is precisely as Beth Simone Noveck noted in her book Smarter Governance, Smarter Citizens, “[there exists] a delicate balance in decision making between democracy, which cannot dominate lest it destroy expertise, and expertise, which cannot dominate, lest it destroy democracy.”

“[Dallas Fed President Fischer’s report on CEO of Texas instruments dismissed as anecdotal by Bernanke] ‘I urge you not overweigh the macroeconomic opinions of the private-sector people who are not trained in economics’.” (pg. 131): I recently read Epstein’s Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World and I was struck by his fantastic review of the organizational theory literature. In particular, he weaved in Karl Weick’s idea on the usefulness of “dropping your tools”. If Bernanke had allowed Fisher to drop his tools of rigorous economics research, and open his eyes to what was plainly reported in these anecdotal interactions and headlines of the business pages, the Fed as an organization would not have lost its sensemaking capacity. The British central banker, David Blanchflower (another lone wolf btw who does not conform to central bank culture), has argued both in his book and recent academic research that this unique epistemological approach, relying on the insights those in the keyboard economy lack, is the “economics of walking about”.

“The rate of price inflation was basically external brake that could be applied to the ZIRP policies,” (pg. 138): My mind drifted here to the similarity with the Marxist critic Walter Benjamin’s comment on the experience of revolutions not as transformational events, but “an attempt by the passengers of the train to apply the emergency brake” on the locomotive of history. I also thought of Powell’s recent comments to lawmakers that, “If inflation does become too persistent, if these high levels of inflation become too entrenched in the economy or people’s thinking [read: expectations], that will lead to much tighter monetary policy from us.”

“The reasons for the Fed’s errors were systemic, and they illuminated how the Fed used its unrivaled research capacity.” (pg. 139): The brilliant value investor, Jeremy Grantham, made a similar point on the systemic nature of Fed errors related to their myopic view on asset prices in this year’s investor note, “The fact is they did not “get” asset bubbles, nor do they appear to today…And what of the Fed’s statisticians? Picked for either their thick academic blinders or intimidated by the usual career risk we all know and love so well – don’t deliver information your boss doesn’t want to hear – they were totally silent or ineffective…nd one of my favorite Teflon men, Larry Summers. What were they thinking with this reckless behavior? That bankers could regulate themselves? The episode was remarkable in many ways as was our willingness to forget it.” Somehow, all of these figures have been revived in spite of their fatal errors during the housing bubble.

“They developed a nickname for it: ‘the everything bubble’…broad-based search for yield,” (pg. 212): The next few subsections of the book are a valuable resource to those trying to gauge the practical consequences of Fed policies, much as Fisher attempted before being dismissed by Bernanke. Hussman also writes persuasively on the chase for yield, “Quantitative easing ‘works’ by replacing interest-bearing Treasury securities with zero interest base money (bank reserves and currency) which someone in the economy must hold as zero interest base money until it is retired….his zero-interest base money encourages yield-starved investors to chase riskier securities…So zero-interest base money acts as a hot-potato that amplifies yield-seeking behavior.”

“‘An entire economic system. Around a zero rate…Do you think it’s costless? Do you think that no one will suffer?” (pg. 219): I find it interesting that people can often internalize Hoenig’s concern when it applies to other people far away like the Chinese, but not when it hits closer to home. Michael Pettis’ (borrowing from John Kenneth Galbraith) description of the bezzle captures what Hoenig intended here. There are a couple principles related to the discrepancy between inflated and real wealth from that article that can be directly applied to the U.S. financial system with repercussions that are truly global, “(1) Notice that the cost of amortizing the bezzle is proportionate to the degree of psychic wealth the bezzle had previously created…(2) It is mainly ordinary households who pay for the reversal of the bezzle, either directly through taxes or indirectly through….unemployment.” Principle 2 is the reason why I am not as certain as many others online that Hoenig’s position is purely faux populism, part of a long tradition of feigning concern for the little guy while embracing the principles of Mellonism that leave them permanently embattled. While I recognize that it is difficult to be in two different places at once, but I don’t think it is necessary to be at the center of right-wing FinTwit to have concerns about the ZIRP regime, a case exhaustively laid out by Leonard in the book. As much as we would like to imagine a world to the contrary, the bezzle has an expiration date.

“‘And believe me we’re in a bubble right now,’ Trump said [at 2016 presidential debate]. ‘…The Fed is doing political things by keeping interest rates at this level. When they raise rates —you are going to see some very bad things happen,’” (pg.228): Trump remains the gravest threat to American democracy, a genie that is not easily put back in the bottle. But he often has insights that have a savant like quality to them. He translated Hay’s covert repolitization thesis as “doing political things” peppering the debate response with trademarked phrases like “believe me”, but I think this is the correct position, at least until proven otherwise.

“They illuminated which parts of that system worked quite well, and which did not,” (pg. 285): Matthew Stoller has written on this disconnect between the system used to deliver money to the primary dealers and the leaky network provided by overwhelmed bureaucracies like the SBA. The point of emphasis is that in each instance the ease of access to new credit creation is not “natural” but a political choice. Adam Tooze highlighted the relevant quote on his Twitter, noting the alternate reality that once prevailed throughout the regional banking system during The Great Compression, following Roosevelt’s shunning of finance at Bretton Woods (1945-1979). Though they have a reputation for promoting austerity, one successfully and the other unsuccessfully, Volcker and Hoenig are perhaps more accurately characterized as children of the New Deal. With the concentration of the big banks, Hoenig now plays in a desolate wilderness.

“A new and troubling term into corporate America’s lexicon, something called ‘a zombie company’….about 20 percent,” (pg. 298). The zombie firm is the naturally pairing of Yanis Varoufakis’ zombie capitalism, a vampire creature that feeds off the blood of debt. These creatures were considered novelties prior to the ZIRP regime, when the proportion of firms that showed these characteristics began to explode.

“‘Everyone had a short-term need that makes the the long term impossible to look to,’ Hoenig said,” (pg. 303). This is what Trump meant when he said that the Fed was doing political things. If you were to ask the authority who appointed Volcker, President Carter, political can be simply read as short-term, while the economic is the domain populated with stately concerns to preserve wealth and power—Sub specie aeternitatis. On these terms, I think Fed policy is just one aspect of a broader neoliberal settlement. As Robert Kuttner once noted, that settlement perversely loses its capacity to reproduce itself economically even as it racks up political victories.

Though for different reasons. Leonard does not expound on the geopolitical dimensions of the crisis, and gives no mention of the Eurozone crisis, as he decided to keep his research focus restricted. Tooze attempts a grand narrative to explain the current moment, Leonard is telling a story.