A Tragedy for Those who Feel

A Personal Reflection on Johann Hari's Stolen Focus

“Impotence and distress of all men in the face of a social machine…a machine for manufacturing…above all, dizziness. The reason for this painful state of affairs is perfectly clear. We are living in a world in which nothing is made to man’s measure; there exists a monstrous discrepancy between man’s body, man’s mind, and the things which at present time constitute the elements of human existence; everything is in disequilibrium. This disequilibrium is essentially a matter of quantity. Quantity is changed into quality, as Hegel said, and in particular a mere difference in quantity is sufficient to change what is human to what is inhuman,” Simone Weil, Oppression and Liberty (1958).

The above excerpt is one of the many fantastic quotes I encountered in my studies over the last couple of days, ranging from the usefulness of history to the divergent French and British fiscal responses to the South Sea Bubble of 1720. This sense of disproportion is perhaps the reason why “this world is a comedy for those who think and a tragedy for those who feel.” I’m left thinking about these ideas from old dead philosophers after reading Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus, a wonderful book that spoke to my own personal journey over the last decade struggling to regain proportion.

In particular, the book connected powerfully to some of my earlier thoughts interpreting David Graeber, Douglas Rushkoff, and, most recently, Chuck Klosterman on why we feel so betrayed by technology. In Kim Stanley’s Robinson’s 2020 commentary on the epiphany that dawned on many that year, every epoch has a different “structure of feeling”, how they experience and interpret events as they unfold in real time. 2020 was one such moment when the structure of feeling gradually then suddenly changes under your feet; the last few days are another. A common point of emphasis from folks who remember the 1990’s is that it seemed like a time of boundless possibility. In that spirit, an entire book was written arguing that the year of my birth, 1995, which also saw the likes of Amazon and PayPal come into the world, was the year the future began. Obama’s favorite cultural historian, Louis Menand, ended his review of the book with a tantalizing cliffhanger—the future ended in 2004, when a few pimply headed Harvard students looking to play an online version of Hot or Not founded Thefacebook. The cultural archaeologists of the future looking to carbon date the slow cancellation of the future may uncover an unlikely site.

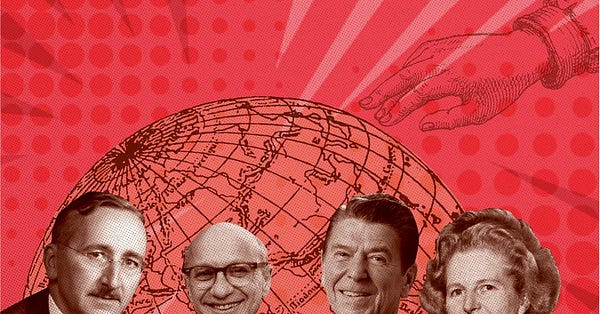

I noted in my 12 Tweets year-in-review post that cultural and economic history combine at these precise junctures. I wrote that connectivity likely has U-shaped properties on productivity. Moderate connectivity when the AOL era spread to every home and office in America was an unambiguous boon to productivity, but instant connectivity of the kind provided by social media would prove to be more pernicious. Though the I-phone is often interpreted as the shining symbol of capitalist ingenuity1, it is also the device that perfectly suited for the neoliberal era in that it ultimately ruins the consumer forces that ensure its capitalist reproduction. The tantalizing theory is that the sharp decline in productivity following the I-phone’s introduction coincided with a more thorough informatisation of the global economy. For reasons appreciated by Nobel economist Herbert Simon in a seminal 1971 paper and panel2 , that informatisation, if not the I-phone itself, directly hampered creative enterprise required for sustained productivity.

But here comes the catch from the standpoint of market analysis. In the long-run, and so far, market participants are still riding Keynes’ tempestuous seasons, Apple’s share price will come down to underlying productivity. After all, the wealth of any security, John Hussman reminds us, is in the denominator. In this respect, the attention economy has been a resounding political success, albeit a success layered over the prior neoliberal successes which have imbibed us collectively for passive acquiesce, but an equally abject economic failure.

The dominance of the attention economy, exposing one advocate’s high-minded appeals to a Stoic mindset as cruel for all but the already privileged, can breed despair, Hari writes. In a world where the choice architecture is designed to engender quantity, how to engineer Hegel’s reverse alchemy to quality, reclaiming the small pleasures that make us human? I do small rebellions like the activity I am doing now as I write in this journal, slowing the pace of my thoughts to the tactile movement of my pen. Bertrand Russell once defended these rebellions in a 1932 Harper’s article, “In Praise of Idleness,” arguing like his Bloomsbury contemporary John Maynard Keynes that these privileges traditionally afforded to the few should be expanded to the many.

David Harvey would probably find these small rebellions as insufficient to stave off the capitalist accumulation driving the Great Acceleration, which has now been turned inwards, but it is all I feel I can muster at the moment.

I recall the imprecise sense that things were accelerating around me in January and February 2020 once drove me to furiously comb through the stacks at LSE in search of an explanation. I was hoping to turn that exploration into a novel project for my behavioral public policy course. I failed in that effort, receiving possibly the worst mark in all my years at university. However, I don’t regret writing the essay as I maintain my doubts that any “nudge” that meets the strict requirements of libertarian paternalism will be effective against the tech bros trained in the insights of persuasive technology to invade our attention with all the wisdom of Sun Tzu. As Sun Tzu might advise, it is more essential to first understand yourself and fellow countrymen.

I can’t speak for others— perhaps my analog experience extending well into the 2010’s through my Senior year in high school is unique. But I am hyper-conscious of the locomotive of anxiety that was introduced in my college years like a parasite that is periodically isolated and contained, but never exterminated. Like Hari, I remember the days when I would pick up Francis Fukuyama’s meticulous political history without a care in world what was happening online or the phantom buzz I imagine in my pocket. I have an intense nostalgia for those days, as many of the problems Hari recounts in the first half of the book detailing his digital detox in Provincetown felt as if I were visited by a familiar ghost. For instance, I don’t believe it is a coincidence that I never experienced insomnia until I became accustomed to staring at my mobile for hours Sophomore year in college.

Then again, the wonderful Substack philosopher, LM Sacasas, suggests hat the endless desire for digital distractions are symptomatic of a chronic loneliness. I have often daydreamed about some kind of campaign to educate citizens on the perils of letting our attention—our ability to attend to something so as to engender personal growth, commons fellowship, or awesome connections with the natural world—fall into disrepair. As Tristan Harris of the Center of Humane Technology emphasizes in the book, it it is difficult to imagine coming to any kind of solution, or even provisional stopgap, to the crises of our time without it. Natural small-D democrats will find themselves stuck in the Kafkaesque conundrum of Adam McKay’s Don’t Look Up, wondering if we should even bother to wake the sound sleepers oblivious to the asteroid hurling down.

Don’t let anyone tell you there is no alternative. We can always take the wise advice Douglas Rushkoff once got at Berkeley, “Find the others.” I find solace in the fact that when people are explicitly presented with Meta’s TINA in their Super Bowl ad, they begin to leave in droves finding the real physical people their platforms refuse to locate. Perhaps the future is not cancelled after all.

And not coincidentally, the device my Chinese professors referred to most often when discussing their desire for domestic brands to climb up value chains.

I included the whole chapter because it is worth reviewing the argument in its entirety, but here is the most frequently cited prophecy of the emerging knowledge and attention economies he foresaw, “in an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.” The larger point can almost be reduced to crude Marxism. There exists a principal contradiction between the Knowledge and Attention Economy, which can only be sustained if a new social caste system emerges alongside it where the executives of the Knowledge Economy do not consume the product they distribute to people’s fingertips, instead opting for meditation retreats around the world.