The 12 Tweets of Christmas

My Twitter Year in Review

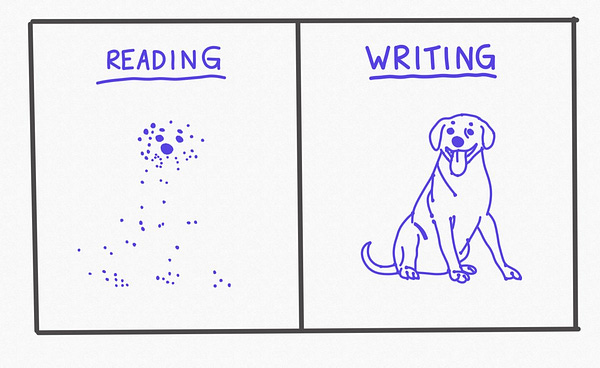

To get into the holiday spirit, I thought that I would create a 12 days of tweets post to review some of the things I have been thinking about this year. Yes, I know this is very lame way to “wrap” my activity on Twitter over the course of the last year, but I couldn’t resist. I wouldn’t blame you if you closed out of this tab or returned to your email. To the rest of you who I failed to scare away, here is my review commentary on the year. The topics range from climate to inequality to asset bubbles to the digital technologies depriving us from sustained attention required for deep work. They may seem quite disparate, but I believe there exists a throughline. After all, writing is fundamentally about connecting the dots to little bits of knowledge which appear to the untrained eye as isolated observations.

On the first Tweet of Christmas:

The thing that I find very interesting about David Wallace-Wells is that he spends an equal amount of time writing on the two great overlapping crises of the global risk society, climate and COVID-19. COVID-19 is arguably the dress rehearsal as suggested by Adam Tooze’s grim warning that “we ain’t nothing yet” and implied in this Economist cartoon:

But there is something even more natural about this pairing of expertise as implied in Holly Jean Buck’s article in a wonderful niche publication, Strelka magazine, on the pitfalls of governance by curve. Her warning, related but distinct from Tooze’s emphasis on the German sociologist Ulrich Beck, is that we should be wary of the temptation from governments around the world to remold unstructured problems into structured ones. In her own words:

“The curve” here encompasses the form, its genesis in narrow-focused knowledge production, and its communication. The curve looks like an advancement in science, in modeling capacity—but it actually results in a reduction in our capacity to fully grasp the situation.

The curve becomes a natural source of legitimacy for these narrow-minded elites. But legitimacy is also Janus-faced as they are terrified that the general population reacting to the exponential properties of the curve— such that in one moment things appear normal only to be rocked to the core in an instant— would engender a mass panic. Stability maintenance officials were certainly driven by this fear when they attempted to put a lid on the severity of the virus when it broke out in Wuhan in December 2019 (link to Nanfu Wang’s wonderful HBO documentary), and continued to misrepresent the statistics well into February 2020 when many in the West were busy “wasting time” under conditions of organized irresponsibility, Tooze writes in Shutdown.1 Perhaps the myth of panic was felt most acutely by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his BJP ministers, who subjected India to multiple total lockdowns—not merely shutdowns—such that it topped The Economist lockdown index for the most days of any other country in the world.

As The Economist noted in an article published last year, the pandemic was a crisis for countries with especially vulnerable health care systems, but also presented an opportunity for autocrats who understand the psychology of fear coupled with isolation. Still, the myth of panic is somehow more sinister as an act of omission. In the backsliding Free World, government officials and messengers at publications like the Financial Times lack an opposite maneuverability for good. On this point, I highly recommend this discussion thread started by Adam Tooze, which I suspect percolated from their comments at a FT Alphaville Q&A on political implications of the U.K. gas crisis.

Commenting on the same gas crisis but bringing his compulsive research of recently revived theorist Karl Polanyi to bear, my old LSE professor, David Woodruff, noted in a thread that the divide between the substantive and the formal economy will likely grow into a chasm in the coming years and decades. Once you account for philosopher Bruno Latour’s provocative but correct revision that the double movement is not merely the people displaced by this gap but also that the planet itself would resist, this Polanyian interpretation is the key to unpacking Tooze’s claim that we are only beginning to observe the epic collision of the Great Acceleration. In the meantime, a specter continues to haunt Europe—bogey figures summoned within inner-elite discourse to justify inaction.

On the second tweet of Christmas:

I did this because I figured that stories in my local newspaper, The Sacramento Bee, are not necessarily on Wallace-Well’s global radar but knew he pays special attention to extreme events and lists them off in his articles for New York Magazine. As it turns out, this story on the Dixie fire would be a warning from the future. The Caldor fire disrupted most of Northern California and knocked on the door of Lake Tahoe. The evacuation of all of Lake Tahoe’s residents to the point that the highways slowed to a crawl as they hurried to get out is another one of those surreal moments this year where the severity of what is currently staring us down really registered for many. I recall a climate action seminar at LSE, where the speaker emphasized that public opinion often does not fully click without an image. We often forget this primary school lesson, but it is difficult to forget when these are the types of images being published:

German speakers tell me these images signify the unheimlich—the uncanny. I think that is a good way to describe our current climate moment. I don’t know if other people have had this experience, but my climate news consumption—and the above tweet is one of many examples— has exposed me to these scientific terms which I had assumed only existed for theoretical value to a practicing community of specialists. In a twist even these specialists could not have predicted, all of the sudden a general audience also feels compelled to learn them to digest our new normality in media res. The climate activist, Bill McKibben, captured the feeling of facing outlier climatic events with increasing frequency from climate-creating fires to heatdomes in a 1989 book2 , The End of Nature:

Summer will come to mean something different—not the carefree season anymore, but a time to grit one’s teeth and survive.

On the third tweet of Christmas:

This observation, referring to Jake Sullivan’s August memo encouraging OPEC, a remarkable document, merits a dissertation, but my readers will have to settle for a couple of links. My first link is a very important joint blog post written by Policy Tensor and Albert Pinto on the gaping chasm between discourse and reality and the strategy needed to avert the hockey stick of doom, which will be all but assured if we double carbon emissions again since McKibben wrote The End of Nature. Similar to Tooze’s thoughts on trillion dollar relief packages to put the pandemic economy on life support, the impending doom of the climate emergency will provide cover for otherwise reluctant and even outright hostile political and financial elites. Their blog post characterizes the fast moving politics of this all quite well, as the left-driven Green New Deal moment is swiftly moving under our feet in favor of the financial stewardship of Mark Carney and Co. warning of stranded assets in a future that pierces 2 degrees. Pinto and Farooqui emphasize the conservatism of this project:

A delicious irony of the planetary impasse is that instead of gradualism, conservatism in the original sense of the term—the desire to preserve what we have achieved; the desire to preserve our cherished institutions—now requires Bolshevism derived from catastrophism….It is in our demonstrable interest to go cold turkey on our carbon addiction.

The intellectual historian, Nils Gilman, writes that when the official future closes off—when the distance between discourse and reality collapses under its own weight— it is the Leninists who win. Elites who have parroted narratives with little results to point to now face an ultimatum. Either they can become Leninists themselves and demand “leaps” or they will be made irrelevant by improvisational strategies to fend off collapse, much as the Russian army turned to wood when cut off from fossil fuels, Tooze writes in the LRB.

The tyranny of living in a dictatorship without alternatives, to borrow Brazilian philosopher Roberto Unger’s phrase, can be spun as grounds for optimism, Tooze argues. Cognitive dissonance is no monopoly of the so-called populists, Tooze noted elsewhere responding to Latour’s indictment of denialist escapism:

But does the preoccupation of climate campaigners with climate denial not reflect an unhealthy fixation?…it is when the doors to the exit are blocked because climate truth has been established that the seriousness of the problem actually becomes clear.

After all, it is Obama who celebrated American “energy independence” as if he were a spokesmen for an oil company, Albert Pinto emphasized in one of his epic threads. The truth of the matter is Obama, Biden, and Sullivan all stare at a version of this chart:

Keynes characterized what it means for genuine statesmen to lead public opinion against these forces:

It is the method of modern statesmen to talk as much folly as the public demand and to practice no more of it than is compatible with what they have said…and furnish an opportunity to slip back into wisdom—the Montessori system for the child, the public. He who contradicts this child will soon give place to other tutors. Praise, therefore, the beauty of the flames he wishes to touch… yet waiting with vigilant care, the wise and kindly savior of Society, for the right moment to snatch him back, just singed and now attentive.

Recall my old professor’s observation about the formal and substantive economy being driven apart? This concept is so intimately related to discourse/reality gap that subbing out the gold standard for planetary impasse works like a charm. Here is Keynes again:

The gold standard…with its general regardlessness of social detail, is an essential emblem and idol of those who sit in the top tier of the machine. I think they are immensely rash in their regardlessness, in their vague optimism and comfortable belief that nothing really serious ever happens. Nine times out of ten, nothing really serious does happen—merely a little distress to individuals or to groups. But we run a risk of the tenth time (and are stupid into the bargain) if we continue to apply the principles of an Economics which was worked out on the hypotheses of laissez-faire and free competition to a society which is rapidly abandoning these hypotheses.

Keynes was an oracle, and remains understudied in undergraduate economics coursework. I am fortunate to have studied Keynes (and Polanyi/Kalecki) more carefully in graduate school.

On the fourth tweet of Christmas:

The reason why this reply resonated so deeply was many people feel they are being deprived of what the author of the linked article, Cal Newport, calls deep work sapping their creative potential. Left-leaning theorists, especially those who call themselves anarchists like the late David Graeber, argue that it is precisely the iron cage of modern corporate structure, condemned to tackling the email inbox and administrative tasks everyday, that prevents us from achieving anything meaningful.

Whenever I think about the question of whether the internet was a mistake, this is the number one thing I think about. It might be true that network connectivity has U-shaped properties on productivity. This would hold IFF moderate connectivity such as that which was observed during the period of the late 90’s and early aughts which Robert Gordon identifies as the Golden Age of an otherwise secular decline in productivity is good for growth and creativity but instant connectivity proved to be pernicious. As the FT columnist, Rana Foroohar, once remarked, while promoting her book Don’t be Evil, the challenges of the global risk society—from climate, to security risks, to inequality— will require our sustained attention. They will require deep work.

I am so wedded to the bit of ancient Greek wisdom that moderation is always best that I sometimes find it difficult to entertain the opposing side. I have had a couple of interactions with the chief American correspondent for the FT, Ed Luce, on the toxicity of Twitter, arguing that Twitter provides junk versions of what we think are genuine mind expansions. A couple months later, I told him that smartest (or perhaps strongest) people among us like Ta-Nehishi Coates stay off the platform entirely.

Obviously I don’t believe this as I wouldn’t be doing this exercise right now. Indeed, I hope to demonstrate in this post that you can extract value from the platform, if for no other reason than to reassure myself. Interestingly, Tooze told Tyler Cowen he at least partially attributes his astonishing range to his constant exposure to what smart people are thinking about on Twitter. Though, I wonder how he strikes this balance between probing for further research and actually getting work done. I suspect in the trilemma known to over-achieving students between quality of creative output, social life, and sleep, he axes sleep.

On the fifth tweet of Christmas:

This paper discussed by Milanovic is what got me started down the road on the macroeconomic implications of inequality, which invariably led me to Michael Pettis. I’ve always had an interest in this subject since I encountered an early version of this chart, shared by OddLots host, Tracy Alloway, in Stiglitz’s book during high school. The patterns are too stark to ignore.

The interesting thing about this quote from the left business observer, Doug Henwood, is not so much the idea, but the year, published even before the dotcom bust. Similarly, on the Chinese side of the ledger, the warnings about treading down this path were articulated incredibly sharply way back in 2005. I’m sure that future historians will examine these pieces of evidence, currently footnotes to the shock of 2008, and play the narrative game of pushing the trigger back in time. This is Marxist historian, Robert Brenner’s basic exercise in contending escalating plunder. I think something similar can be said for the post-modern dreamlike fantasies of the fintech/crypto space. What we currently regard as novel in the moment was pretty aptly characterized by Henwood’s book in 1998.3 Future historians will no doubt recognize these patterns.

As a parenthetical, I deeply enjoy bringing Doug Henwood into discussions online. He reveals fascinating anecdotes about people he met in person back in the day, like this one of Stanley Fischer. As I note in that thread, there are many projects to be done on Fischer and the MIT economists as a distinct school of neoliberalism. He also shared a fascinating anecdote of the slowness of an unnamed investment manager in the different era of the 1970’s when discussing Robin Wigglesworth’s book, Trillions: How a Band of Wall St. Renegades Invented the Index Fund and Changed Finance Forever, which he mysteriously deleted. Maybe someday I will make a podcast to extend out these stories. Until then, I will have to settle for his Behind the News podcast, like this episode with Max Krauhe, author of a remarkable article in the FT on the need for planning.

On the sixth tweet of Christmas:

Pettis has an engaged following for a reason. Readers might be interested in my Twitter thread shared by Pettis and his co-author, Matt Klein, on their book, Trade Wars are Class Wars. I also highly recommend Tooze’s interview discussing the book.

I discussed this podcast with another guest on OddLots, Travis Lundy. Lundy does an excellent job of summarizing and supporting Pettis’ main point that there are no good options regarding pricking China’s housing bubble, and that the Japanese saying therefore resonates, “it can’t be helped.” Unexpectedly, Lundy, who I know as a hard-headed analyst, revealed some fascinating sociological observations about the moral implications of bubblenomics from the time he spent in Japan in the late 80’s to early 90’s. He echoed the growing chorus that Japan performed quite admirably against demographic challenges.

On the seventh tweet of Christmas:

When I encountered Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff’s article on Peak China Housing, co-authored with a Tsinghua economist, Yuanchen Yang, early this year, I couldn’t quite describe what drew me to it other than I knew from personal experience in Beijing that real estate prices did not reflect actual value. To the uninitiated, it is difficult to describe what it is like to go apartment hunting in Beijing, where little rooms in ice box apartments go for multiples of rents in much nicer global cities. While lacking rigor, this intuition is a perfectly legitimate basis of knowledge that should not be dismissed. The British economist and former BOE central banker, David Blanchflower calls it the economics of walking about. As is often the case with these intuitions, empirical support usually follows. This is the Rogoff chart that set off alarm bells.

I had a head-start when China’s debt crisis began to snowball in August with the steady stream of Evergrande news, though not as much as Pettis who has been warning of the consequences of delay for years. The timing is interesting, coinciding with the summer blizzard of regulatory actions that revealed stubborn resolve/ willingness to stomach short-term pain from the top—offhandedly emphasized by Tooze in his chartbook, endorsing from Xi to Stalin claim. This political change, which Barry Naughton notes is an acceleration from an already quickened pace around the pivot of 2015, is largely explained by base effects, Lizzi Lee speculated in a SupChina discussion of the Red New Deal.

Yet a soft landing to the Evergrande crisis is not merely a matter of resolve as it involves rebalancing an economy that is not so dependent on property growth to sustain arbitrary, or “inflated”, growth targets by shifting income from local governments to households. It is primarily for this reason that economic regulators are not as sanguine as the political class within the country on the ease of transitioning away from unbalanced development and disorderly accumulation of capital. There is a very interesting divide between these economic and political analysts, or those who are familiar with the details of economic accounts and those who traffic in narratives. Reviewing the Rogoff statistics, Bloomberg’s Matthew Brooker similarly argued that it is not so easy to step off the property treadmill. When the mountains are high and the capital is far away, pulling the emergency brake on provincial elites who have come to rely on revenues from property sales may be more destabilizing than the alternative of allowing social dissatisfaction among ordinary urbanites to fester. As Pettis might say, there are no good options at this late stage.

I believe the HBR article, riffing off a seminal 1982 article on how power and purpose covary in international regimes, struck a chord with Pettis because he is so attuned to the narratives which invariably envelope pundits when bubbles reach the apex of their mania. The geopolitical implications are never quite as severe as they seem in the moment. He correctly fixated on how the geopolitical obsession with Japan of the late 80’s maps one-to-one to China’s project to steer human and physical capital to semiconductors, AI, and other industrial policies with increasing returns to scale in the attempt to streamline state capitalism in the service of national power. The interesting thing about China is save for its sheer size, how unexceptional it is from a historical view. Taggart Murphy’s banal punditry will no doubt sound familiar:

The vast majority of Japanese—most emphatically, the political and business elite—do not believe for a moment that the country’s way of doing things is applicable abroad. or that Japanese social arrangements in the business, financial, or cultural spheres are at all analogous to what takes place in other countries. The only real ideology Japan has is an overwhelming sense of its own uniqueness.

However, the author was not banal in every respect. You would be forgiven if you mistook this passage for Pettis:

Japan’ssurpluses tend to end up with financial institutions and corporate treasurers, which are hard-pressed to find investment opportunities. Ultimately, much of the wealth disappears into stock market and real estate “sinks”. This is precisely the situation Keynes diagnosed as the cause of prolonged depression: savings inadequately recycled as demand.

That malinvestment which appears to only prop up asset prices with little to offer in return would foreshadow the current run-up on all assets classes, which may very well end up as the one bubble to rule them all.

On the eighth tweet of Christmas:

I was responding to an article written in the FT by Gillian Tett on the Japanification of China. I know of Ann Pettifor’s tendency to lecture students on the etymology of credit because I had the luxury to attend a small seminar at LSE where she gave a guest lecture. She simplifies irreducibly complex financial systems to be able to identify the art of when these promises to pay surpass actual capacity to pay. When signals suggest this line is crossed, debtonation day is only a matter of time. Policy Tensor’s summary of the concept, a 2017 article on China’s growing debt distress, draws from Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis:

Credit booms have a clear mechanical path. An exogenous increase in the risk-bearing capacity of the financial sector drives a lending boom. Credit-to-GDP ratios rise. Debt service ratios follow. At some point, debt service becomes too onerous to sustain, the lending boom is arrested and a financial crisis breaks out.

The complication for investment practitioners is that the trigger is never purely mechanical, and complexity makes a mockery of central bank and regulatory attempts to engineer markets. For this reason, to begin Mad November, I wrote a bit on why philosophy is required to assess metaphysical notions of value. The overall message was to acknowledge that the old Keynesian adage that the market can remain crazy far longer than a value investor can stick to the courage of his convictions and remain employed has more than a grain of truth. But in the end, I am too influenced by my time at LSE, the institution that provided the same inspiration to a variety of thinkers ranging from Hirschman to Soros, to believe that financial markets can be engineered, no matter how much expertise Powell commands at the Fed.

My blog post was at least partially an ode to Jeremy Grantham, who delivered a brilliant polemic in August that the Fed does not actually have the power many attribute to it. Rather, it is in the belief in its power that gives it the appearance of having forever banished the problem of deflationary shocks to the ash bin of history. The logic seems foolproof except for one fatal blindspot, asset prices. Japan learned that crazy valuations do not go up forever; they eventually come down to the physical world of growth.

More concretely, Pettis noted that historically it is an aberration for wealth to GDP to exceed a multiple of four. While China’s deviation driven by a bloated real estate market and remarkably underdeveloped equity market is larger than the world at large, both are quite substantial with China surpassing ratio of 8 to 1 and the world 6 to 1. Now would be a good time to bring asset prices back in to Fed models. As the one-time bureaucrat at the New York Fed tasked with the collapsing hedge fund LTCM, Peter Fisher, reminded PBS viewers this year, the risk of one of the great financial calamities of all time is extraordinarily high—one in three? Higher?

On the ninth tweet of Christmas:

This idea germinated when I read Nils Gilman’s substack on post-neoliberalism. He joins a growing cast of intellectuals who mark 2021 as the end of the Friedmanite neoliberal consensus. Haunted by the wage-price spirals of the stagflationary 70’s, central bankers and financial elites settled around corporate profits and monetary stability as a bulwark against the power of organized labor. The chorus is reacting to headlines noting that inflation is the highest since 1982, and perhaps more significantly policymakers, chiefly Janet Yellen, are intentionally overshooting the U.S. economy. At the start of the pandemic, Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff did the rounds on the evening news programs, arguing the whole point of the belt tightening of monetarism was so that policymakers could run the economy hot without inducing the dreaded wage-price spirals in the event of novel economic shock like coronavirus. He implied that those who favored drive-in breadlines could not draw from serious economics. They would have to revive the 19th century zombie ideologies.

For all these reasons, Cederic Durand’s argument in The New Left Review that 2021 is the “1979 coup in reverse” resonated. Similarly, Dutch historian, Rutger Bregman highlighted the influence of statist French economists, Gabriel Zucman and Thomas Piketty, and a group of heterodox female economists who have fundamentally transformed the ideas that are lying around. As Steadman-Jones wrote in one of the authoritative histories on the conditions that brought about the neoliberal transformation of 1979, changing these ideas are a necessary but not a sufficient condition. Policy entrepreneurs also need a good crisis, and can’t let it go to waste. The transatlantic neoliberal movement did precisely that in packaging their ideas in Thatcher and Reagan.

Gilman offered a hopeful argument that Biden offers a similar vehicle for an opposing project. He pointed to a laundry list of signals, which together amount to a repudiation, not just of Friedman but of the bipartisan political applications:

Virtually every one of the shibboleths of neoliberalism listed above is in the process of being repudiated. Deficit spending is back with a vengeance; industrial policy again in vogue, not just with liberals, but also with conservatives; instead being considered a bogey, inflation is being treated as tolerable; unemployment related stimulus checks are going out to working people and families with minimal concern for reducing work incentives; government-funded public works projects are back, this time with an environmental twist; top marginal tax rates are set to rise, and a global corporate tax accord is in the works, backed by the IMF, the United Nations, and the U.S. Treasury itself.

I am more skeptical because this list may seem exhaustive, but it has one crucial omission emphasized by the authors of the Noema piece. Because the economy of the last 40 years has been defined by wage rigidity, asset inflation logics (i.e. compare the net worth chart above with this RAND corporation inequality study), a person’s life chances are increasingly unrelated to work but rather whether that person is in line to inherit an asset which will appreciate in value. Particularly for young people, it is perfectly rational to seek alternative means to advancement through the exuberant promise of crypto or rally around improvised labor strikes facilitated by social media. Call it The Great Escape. There is no alternative—to make work pay again.

While the comfortable yet enlightened class who tend to get their way might prefer to run the economy hot on all fronts so wage and asset inflation coincide, I suspect only a thorough reversal will do. Admittedly, I have not yet engaged with the Berggruen Institute idea of the Mutualist economy, in spite of of Gilman pointing me in that direction after he saw one of my Twitter threads demonstrating my interest in the post-neoliberal future of capitalism. If by mutualism, they mean tackling regional inequality so the parts of this vast country do not devolve into balkanized interest groups and sow political discord as we head further into the Turbulent Twenties, themes explored in Alec MacGinnis’ Fulfilled and Ed Luce’s The Retreat of Western Liberalism, I’m onboard.

But in their New Deal for Wealth, I am hearing something different. People who have earned their comfortable position in society have an awesome deal. They can invest in any number of assets, chiefly in tech, which due to network effects and wide moats are all but guaranteed to deliver awesome returns. The question seems to be— given that we have this Midas touch how do we extend our reach to other groups who are not traditionally afforded with our opportunities? The point I wish to emphasize here is what appears like a deal that is too good to be true to those parking their savings into index funds buttressed by high performing GAFAM’s, that is because it is. There is an escalating plunder built into these assets as constructed, where a steadily shrinking class of owners benefit from asset inflation at the expense of non-owners.

French economist Thomas Philippon argues today’s big firms are historically unique in that they are fiefdoms disguised as corporations. They can extract huge rents without leaving much of a footprint. Amazon’s physical marketplace and warehouse infrastructure is the exception that proves the rule. In other words, these firms are perfectly situated for the wage rigidity, asset inflation conditions of the neoliberal settlement. They might enable small businesses to get discovered on their platforms, but they have no interest in engendering what Roberto Unger calls inclusive vanguardism, the key to unlocking the productivity limits identified by economist Robert Gordon’s research. Small business—what Unger calls the 19th century professions—will continue to be unjustifiably valorized, while the apex of the knowledge economy remains firmly under wraps in corporate parks in Menlo Park, Cupertino, and Palo Alto.

Betraying the Utopian promise of the internet when it first came to the fore in the early 90’s, knowledge production today is paradoxically restricted. Mutualism will ring as hallow as the Biden Administration’s well-meaning laundry list of reforms unless it is coupled with Unger’s vision. The fact that the philosopher with the most compelling vision for post-neoliberalism in the 21st century is Brazilian should be lost on no-one. According to the emerging logic of the American knowledge economy, Brazilization means that enclaves within the flat coasts will take the pecuniary value derived from the possession of knowledge assets, leaving virtually nothing for those who are shut out in the favelas.

On the tenth tweet of Christmas:

For many, the events of January 6 were the wake-up moment to the “newly overt Caesarism of the American far right, ‘a place broadly codeterminous with fascism’”. I reached a very similar conclusion in my bleary eyed blogging when I returned from the UCSD Price Theater watch party following Hillary Clinton’s 2016 election night loss. At the time, I was reading a book written by a wonderful old China hand, Theodore H. White, who has a fascinating story from humble beginnings in the Roxbury neighborhood of South Boston to Fairbank’s Harvard to meeting Edgar Snow in China to an esteemed presidential historian. Interpreting the immigration-tinged demagoguery of Caesar as triggering the downfall of the Roman republic, White wrote in 1978 that no such event seemed likely in the near future. The take-home point from my blog is that it had arrived.

I still stand by that claim, albeit in a first as tragedy, then as farce pattern. The critical component of the historical analogy, which of course is flawed4, is that Trump has merely retreated into exile at Mar-a-Lago following his 2020 election loss. Like Caesar, he remains and is likely to return at any moment. Legacy media outlets are strangely complacent to that reality, still hypnotized by Trump’s farcical theatrics.

Ezra Klein of course is an exception because he still remembers his Monkey Cage blogging days during the Bush presidency. While today might be different, he is an astute observer who understands, like Evan Osnos in a recent book, that the forces that are driving these ugly passions have been percolating for a long time. I am not as old as Ezra, but even I remember the way conservatives absurdly discussed martial law during the early Obama years, believing he was a socialist. We both know the paranoid fascistic tendency in American politics is nothing new. Yet it has no doubt become more available by the proliferation of right-wing media sites supercharged by social media.

The fertile space of the sprouting conservative media ecosystem belies the concentration at the root, which centers around one key figure who passed away this year from cancer, Rush Limbaugh. More precisely, it originates in the Big Lie he peddled on the four corners of deceit in academia, science, media, and government. Damon Linkler characterizes that belief as a stones throw away from outright fascism as we soon discovered on January 6:

That the current American "regime" is most accurately described as a "theocratic oligarchy" in which an elite class of progressive "priests" ensconced in the bureaucracies of the administrative state, and at Harvard, The New York Times, and other leading institutions of civil society, promulgate and enforce their own version of "reality."

There is perhaps no better representation of the authoritarian mind than Rush Limbaugh. He used his dying moments to favorably compare the capitol rioters to the American revolutionaries and stoke fears that minorities are in the driver seat of the Democratic Party, referring to Kamala Harris’ swearing in at inauguration. Though he hoped to couch these rants with plausible deniability as a mere provocateur, I believe that the historical record will nonetheless properly reflect that his “entertaining” was inimical to a functional democracy. A chapter in a book on Rush’s assault on reason and reality, a glorified Alex Jones, leaves little room for doubt, gleefully watching American democracy and the planet burn. In short, the evolution of the conservative media ecosystem following purity spirals from Rush and Bill O’ Reilly to Alex Jones and Nicholas Fuentes, the radicalized college student profiled in The New Yorker’s extraordinary first draft of the capitol riots, is first as tragedy then as farce in miniature.

On the eleventh tweet of Christmas:

I noted in the previous tweet commentary that there is a short little book, with a title that poses a provocative question, Are We Rome? Unfortunately, I do not know enough about classics to pretend to answer. From my glance at this history, I have reached the conclusion that the parts of an empire governed by reactionary land power have a tendency to subsume the parts that are governed by liberal sea power. In the ensuing struggle, the reactionary power’s sine qua non is to never cede even a single inch. Think Sparta during the Battle of Thermopylae but for D.C. statehood.

The traditional explanation of China-U.S. is that of the Thucydides Trap, or a rising power colliding with an established power. There is not a single China scholar I’ve ever interacted with who gives much weight to Destined for War as an idea to be taken at face value. They are far more likely to highlight the cleavages within their respective societies. For China, the dilemma is whether to lean into its urban AI superpower or to make what Stanford Professor Scott Rozelle calls insurance investments in rural areas.

President Xi’s leanings on this question are an open secret. The most persuasive argument against Xi as a return to Mao is that rural peasants are not his constituency and rural concerns are largely an afterthought in his Qiushi essays and speeches, mentioned but not prominently. According to David Shambaugh’s personality archetypes of Chinese leaders, Mao was a populist tyrant, a contradictory pairing made possible by his rock solid support among the rural peasantry.5 By contrast, Xi is a modern emperor, somebody who, like Jiang Zemin before him, has to play to a more diverse set of constituencies through the drama of the imperial court at zhongnanhai.

More broadly, however, the return of ideology under Xi6 represents a resurgence of the geopolitical, if not domestic, dimensions of reactionary power. One element of the classic fang/shou dynastic cycle that appeared to go dormant over the last 40 years coinciding with open-up is between closed, ethnocentrism and open, cosmopolitanism, symbolized by conservative Ming emperors and the perennially distrusted merchant explorers. The Chinese legal scholar, Carl Minzer, places China’s recent inward turn in that historical context by invoking the distinction.

The political psychology of the coastal/interior divide may be universal, but those divides are interpreted differently. In the West, the fear in academic, media, and political circles is that reactionary power will subsume the aspects of the system that yield dynamism, sparking a gradual decline that ends in spectacular society-wide collapse. In triumphalist new China, anxieties are more limited to the intellectual and activist class. They contend the centralization of power makes it less likely that rural-based elites, the gentry, will completely dismantle the state in this way. Instead, cycles alternate between open and closed periods for centuries until systemic weakness of society compels imperial action for common prosperity. The fixation is not on collapse but foreign intrusion. A question analogous to Cullen Murphy’s emerges: Is China Ming?

On the twelfth tweet of Christmas:

I’m not sure how much I want to elaborate on this point raised by the oil man quoted in Paul Mason’s BBC piece, written in 2011 and nailing Palinism as the future of the GOP. That oil man told Mason that no matter how many simulations he ran, there are none that avoid civil war between the reactionary land power faction dogmatically in support of fossil capital and the liberal sea power faction that favors phasing it out entirely. Peter Turchin’s cliodynamics offers a similar theory of the case, though it rests on an ecologically-inspired view of inter-elite competition devolving into political violence. When violence of the kind we saw on Jan. 6 is accepted as legitimate recourse—merely politics conducted by other means—political stress turns exponential. We are on track for the future Turchin and Goldstone predicted, The Turbulent Twenties:

I am more than a little skeptical of the above chart. I share Ezra Klein’s view that it sanitizes the tumult of the 1960’s. Though I will caveat my skepticism by noting that I am not a good forecaster of exponential growth. If the dynamics Turchin models coupled with climate hell come to pass, I cannot be sure how those accustomed to the niceties of middle class life will respond. The shocking thing about the grid failures in Texas, as Ezra pointed out in his column in February, is how all these taken-for-granted assumptions of modern life were very nearly wiped away by an event that was in a statistical sense, pretty tame. What happens if things really fall apart as exponential decay of unraveling complexity suggests? Are the systems that are currently in place anti-fragile and resilient?

Adam Tooze told Ezra that initiative would entail wrestling the supply-side away from conservatives, much in the same way another climate commentator, Holly Jean Buck, argues that we, as progressives, ought to reclaim the rhetoric of freedom. Freedom is fundamentally about the recognition of natural necessity, a fact we should have learned after multiple waves of avoidable shutdowns. Empowering the future is not about quarrelling over what we can afford, but what we can actually do.

Against the locked-in forces already on the horizon, that capacity building project for substantive freedom may seem destined to frustrate. I remarked in a conversation with Holly Jean Buck that, if 2008 and 2020 tell us anything, most are extraordinarily ill-equipped to assess counterfactual crisis scenarios. The *well, actually many more would have experienced financial hardship in 2008 and got infected and/or died in 2020* always and everywhere strikes people as disingenuous as it cannot be independently confirmed, even when it is emphatically true. Tooze’s books, Crashed and Shutdown, acknowledge this critical difficulty, but focus on the details of the improvised strategies required of living in global risk societies where normal accidents recur. Abandonment may have been an available option to Charles Perrow concerned by the risks posed by nuclear technology as tightly coupled systems of interactive complexity, but not when it is the energy and financial system writ large. As anybody who has sat down with modern derivatives markets can attest, under complexity it is difficult to merely characterize present relationships, to say nothing of what could have been. Albert Hirschman had a motto suited for overshooting complexity, a precautionary principle for an age of crisis, “we don’t know, but we must try.” A corollary is that given the severity of the crisis that currently confronts us, I don’t believe it is possible to overshoot, but policymakers ought to be bold enough to try.

I hope that Tooze’s recent thoughts on the promise of climate finance are laying the foundation for that policy-making—as Peter Drucker once remarked what gets measured, gets improved. But currently reactionary land power, in the form of Joe Manchin, is revealing its true color, not ceding an inch in his legislative wrangling with Democrats. That intransigence does not bode well for Tooze’s creative range as it all but guarantees that he will have to make Crashed into a trilogy, covering the third node of the overlapping crisis, the beast that lurks just outside the ring in The Economist cartoon.

No easy way to make the transition from that dark thought, but I do mean this sincerely:

Merry Xmas! I hope everyone enjoys their time unwrapping presents and spending time with family.

Nanfu Wang wondered why it was so easy to go through customs in New York in February even though she had contact with Wuhan and she suspected her young daughter may have had COVID-19. Tooze similarly notes on a podcast with Nathan Tankus, Notes on the Crisis, that it was bizarre to keep airports open thinking the virus would remain contained in Wuhan as if it belonged to some oriental fantasy or Maoist backwater and not a key hub of the global economy.

Readers who are older than me will not fail to recognize the significance of this year. With the triumphalism of the End of History also ushered in the End of Nature. I hope to find a more extended look at this juxtaposition in Tooze’s next book on the great acceleration, assuming of course that future events do not compel him again to rehash the extraordinary crisis responses to backstop the global financial system. The long decade of financial crisis may very well turn into our own “interwar” crisis 110 years later, which if that does in fact come to pass makes Tooze the ideal candidate to write these instant histories.

And perhaps another, Frederick Jameson’s Postmodernism.

The author of a book on the connection once listed off the ways Americans and Ancient Romans inhabit different universes.

Populist tyrants in democratic and authoritarian settings often follow this pattern. They only have one constituency, but there would have to be an event akin to religious conversion to lose that constituency. This mass of devout followers make it all the more tempting for the cult leader to declare them “to storm the barricades” when their power seems threatened. Herein lies the connection between 1966 in China and 2021 in the U.S.

As Soros’ essay in the WSJ indicated, an old reality but increasingly recognized by financial elites who up until now have been largely blinded by the GDP fallacy.