Development: A Journey for All

Revisiting My PKU Thesis, Responding to Dercon book & Tooze Review of Delong

“To live in peace is only one of the key human rights….The Universal Declaration promised to all people the economic, social, political , cultural, and civic rights that underpin a life free from discrimination, want, and fear. As with the United Nation’s promise of sustained peace, these promises of human rights have not been realized. It seems that there is a steady reduction in the number of things in which we can have faith…evolution is a global process…I believe it has been God’s plan to evolve human beings [from animalistic man who vies for resources to the ubermensch who bargains that only way to sustain resources amidst the fragility of complexity is to cooperate], and that after thousands of centuries we know find ourselves uniquely endowed…an inherited duty to contribute to moral and spiritual advancement…It is sobering to realize the average human intelligence has probably not changed appreciably during the last ten thousand years….[Rather] the process of learning has greatly accelerated during recent times with our improved ability to share information rapidly. For the first time, we have become aware that our own existence is threatened by things such as nuclear weapons and global warming. These recognized threats are, perhaps already an ongoing test of our human intelligence & our freedom…The human challenge now is to survive by having sustained faith in each other and in the highest common moral principles that we have spasmodically evolved,” Jimmy Carter in Faith: A Journey for All. My note was not written in the book, but paraphrasing something Carter said in a Q&A session I attended in February 2018 at The Carter Center.

“天地之间,其犹橐龠乎?虚而不屈,动而愈出。多言数穷,不如守中,”老子.

“The space between heaven and Earth is like a bellows.

The shape changes but not the form;

The more it moves, the more it yields.

More words count less.

Hold fast to the center…

The Tao begot one.

One begot two.

Two begot three.

And three begot the ten thousand things,” Ch.5 & 42 of a 1989 translation of Laozi’s Dao de Jing.

I wanted to give the spotlight to an excellent book, Gambling on Development, I read recently in advance of Stefan Dercon’s lecture at the LSE this week, the first of what appears to be a superb Fall program. On the off chance that this blog should reach Dercon’s desk, I apologize in advance as the points he makes in the book deserve fuller treatment. Instead, I intend to pull out just two observations from Dercon’s masterful yet lively account of everything about the good enough political economy needed to escape the straightjacket of governance traps.

They relate to the execution of the neoliberal turn in two countries, Bangladesh and Uganda, in pursuit of structural transformation. I will be crafting a nonsense narrative that draws from dates which are purely arbitrary. In the spirit of the Chartbook exercise and with a method adapted from my Peking University thesis, I hope to share a series of charts and tables which will point in a deeper direction. Is the narrative Brad Delong tells in Slouching Toward Utopia self-obsessed, failing to step outside the cave of American power and see the world as it actually is, as Tooze contends? That is an incredibly serious charge as it attacks Delong’s motivational drive—not an honest effort to understand gravity’s return, merely to lament and execrate as if defying gravity circa 2005 was sustainable. Delong dealt with it well.

I would like to interpret Tooze charitably. When examining the shuddering end of the long 20th century, the rhythms will look broadly similar regardless of where you look. In particular if you take the period of say, 1995-2005, there is a sense of disappointment following unbridled ambition. The future began in 1995 and ended in 2005. Critically, the disappointment did not reflect a starry-eyed optimism from tech enthusiasts without any actionable plan to execute. No, the aims were largely achieved as intended, but the transformations were not as deep as conceived, the big picture point of my review/reflection of Delong’s book.

And so goes America so goes the world. At precisely the moment America’s self-understanding of itself as risk agents inhabiting the Age of Disaster as the ball dropped at the new millennium, that collapse in optimism created an opening for The Age of the Strongman elsewhere, beginning with Rachman’s archetype, Vladimir Putin (1:39:30-).

That narrative is appealing but it overdetermines the relations between rhythms. It is a variant of the simplistic bedtime fiction Curtis criticizes of America as a force for good against a parade of villains. An axiom of the modern world is that under complexity, it is possible to draw a hidden unified order between any series of schema, but these representations are sensemaking endeavors. In the real world—a truth we can only grope, not grasp— events occur independently, simultaneously recombining divergent and convergent strands, a spasmodic evolution. The narrative arc of unbridled ambition giving way to disappointment as a convergent strand is easy enough to understand—the U.S. and Bangladesh stood at very different places in 1971.

The divergent strand is just as critical, as the “successful failure” aspect of most development projects around the world have a common legacy in the British empire. Dercon writes Bangladesh was “the country of laissez faire” and has an extended riff on how it pays for economic notables to have political connections to insulate emerging business models from risk, just as was true for its Gladstonian counterpart. Similarly, he notes that Uganda during its period of structural transformation and under the stewardship of technocratic leadership at its central bank was the last believer in the Washington Consensus.

Their neoliberal turns delivered results. An authoritative economic history of Bangladesh’s recent development history concludes, “Along with creating a successful growth story, Bangladesh has become a role model for other countries. It is widely considered as one of the rare examples of a poor country becoming a regional economic powerhouse within a few decades by following prudent economic policies.” I noted in my Peking University thesis of structural transformation patterns how, even in my total ignorance, Uganda’s statistical performance popped off the screen:

“Interestingly, the country with the lowest share of total revenue from extractive resources, Uganda, is also the best performer in the sample, sustaining upward trend toward greater complexity over the last three decades.”

Yet neither of these countries are exceptions to the rule, I would submit a general law—call it Khan’s law— that not a single development superstar achieved their place atop the global hierarchy by adopting Washington Consensus orthodoxy. Paraphrasing the great Cambridge economist, Joan Robinson, Dercon concludes that countries like Bangladesh and Uganda that are consciously self-aware of their own limits and the Quixotic task of “getting a better history” often can do little better than settle for the privilege to be exploited.

To understand where they fell short, one must understand what a prototype transformation looks like. To do that, I’ll be returning to the favored year of Toozian thought, 1989. Though, the story I choose to tell—again, nonsense— is less centered on Václav Havel, more on Laozi.

Taiwan: The Structural Transformation Prototype

“The real hinge of history is not 1870 when some kinds weird things begin happening in the North Atlantic backwater but the 1976 succession to power of Deng Xiaoping and 1986 succession to power of India and both China and India, and also Indonesia and also the rest of Southeast Asia begin to start making the neoliberal turn themselves. And that their version of the neoliberal turn and the growth we’ve seen since in Asia are the truly decisive things that have happened since 1980 and the only thing historians in 2100 will think worth focusing,” Brad Delong reflecting on his book on the Hexapodia podcast with Noah Smith (~54:00-55:00). This is what I was thinking about when I typed up the Laozi quote in the intro hook. The “one” is the UK, the “two” is the US. I think Slater and Wong in From Development to Democracy make a persuasive case the “three” is Japan. And the rest of this entry will be devoted to the ten thousand neoliberal turns.

Delong is broadly right. I recall reading in my MMW coursework (a history sequence at UCSD), and one book in particular, The Origins of the Modern World, that under the broad arc of history, the two overwhelming forces structuring the global economy were the two superstates in the East, China and India. Past is prologue:

But the dates are wrong, at least for India, as implied in the line of Noah Smith’s further questioning on South Asia and Africa, the two regions where the Bottom Billion are concentrated following the rise of East and Southeast Asia. If he were to insist on keeping 1986 for the neatness of the narrative, aligning with the ten digits on our hands, he would have to revise the country to Vietnam, standing in for Southeast Asia:

Vietnam began its economic reforms [not Reform and Open-up 改革开放 but Renovation] Đổi Mới to transform the centrally planned economy to a regulated market economy in 1986….Along with domestic reforms, extensive reforms were underway to open the economy in 1989. The impact of these reforms was dramatic…transforming what was then one of the world’s poorest nations to a lower-middle income country by 2010 (Mujeri and Mujeri 2020, p. 18).

1989 is the hinge in so many historical narratives, because this is the year when the Asia my grandparents visited, what they called “the Orient”, pictured below, forever vanished.

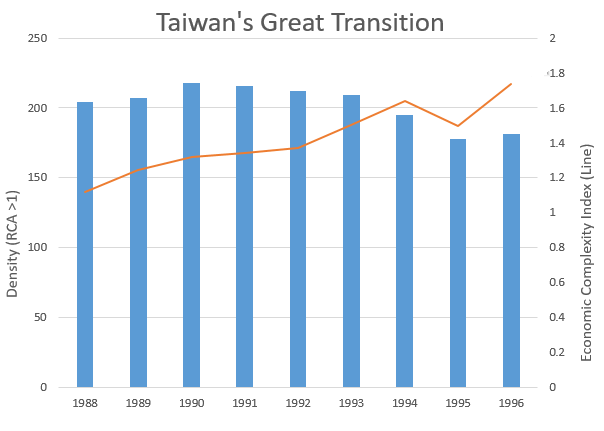

The Great Transition was underway, economically as well as politically. In fact, it can be said that the The Great Transition is still underway because the period from 1988-1995 in the Republic of China, represented about a doubling of per capita GDP from a base approximately equal to the People’s Republic of China today (the Bolivia part). By the rule of 72, that is approximately a 10 percent per annum growth rate. I side with the China bears, from Patrick Chovanec to Logan Wright, because I am skeptical China from 2021 can pull off a similar feat.

The main idea of my thesis, reviewing the Hausmann Atlas of Economic Complexity dataset and recycling early 2000’s growth reports, is of a statistical recurrence of three stages of development as well as two transitions between those stages. At first, there is a factor economy with association as its method, through intervention can transition to a scale economy, and finally, through means that are more mysterious but relate to fostering communities of engineering practice, can incubate the knowledge economy with counterfactual imagining as its method.

Making the final ascent up the ladder rarely occurs and never spontaneously, but when it does it is clearly visible. To increase economic complexity in initial stages, essentially the only thing that matters is expanding the scale of the product space. I wrote that the aim of the first transition is simply to increase the density within the product space with little regard for the position. The density is represented by all those products in the 4 digit SITC classification system with a revealed comparative advantage greater than 1 (see Hausmann methodology). Hausmann’s dataset marks Taiwan’s transition around 1990 when the density of the product space peaked, but even as the scale economy started to recede thereafter, economic complexity continued to ascend because the country deftly navigated a favorable product space to climb up value chains.

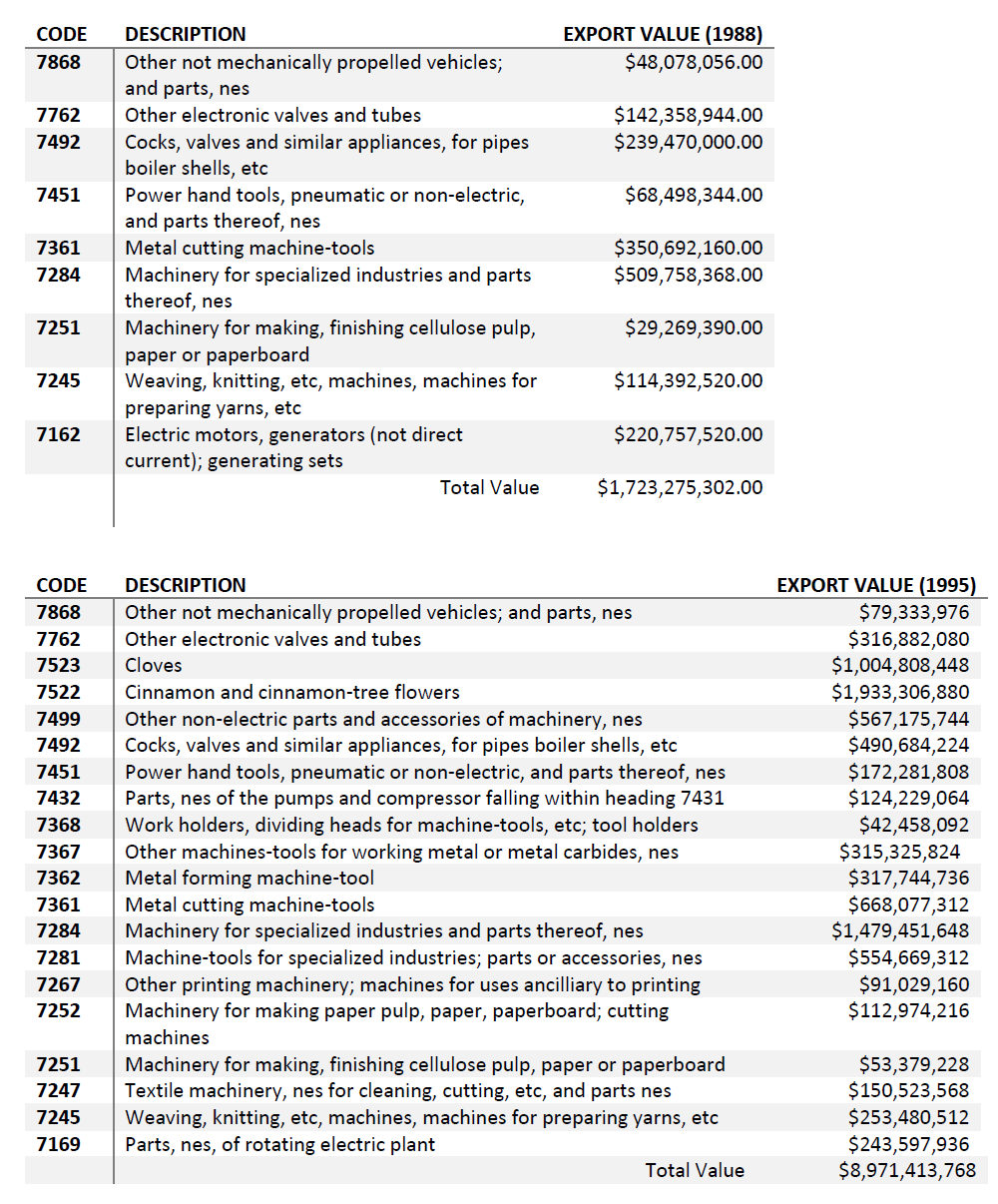

To illustrate, below are two tables of all the products in the “7” category of the single digit classification, machinery and transport, with a product complexity above the Taiwan’s ECI in 1988, and the associated export values. The capabilities existed in 1988, implying high complexity opportunity gain, but were greatly expanded seven years later, reflecting a dynamic evolution of its comparative advantage.

Put in a pin in both of these figures as they are very different for those with a product space evolution demonstrating static comparative advantage, even for those cases that have moderate success in experimental development of certain core industries outside manufacturing without special Kaldorian properties. Those properties pertain to the larger growth process and are as follows: (1) strong casual relation between manufacturing and economic growth (2) strong casual relation between the growth of manufacturing and the productivity of manufacturing and (3) expansion of manufacturing facilitates productivity growth outside manufacturing. Inventing invention. On that note, we return to the two cases of emphasis extracted from Dercon’s narrative, Bangladesh and Uganda.

Developmental Bargains Begin as Quiet Revolutions (1988-1994)

I think there is a classic fallacy in development economics that, once the process of transformation is set in motion, the execution is largely linear and uniform. The misconception is related to the peculiarity of the East Asian transformations. In the aforementioned history of Bangladesh, they have a section titled the “Uniqueness of Structural Transformation”, referring to patterns of premature deindustrialization in Bangladesh. The formulation is backwards; the handful of Taiwanese-like transformations that transgress those patterns are unique.

Though, I now realize that data analysis is protean. It depends on the story the researcher performing the analysis seeks to tell as well as arbitrary method choices. I also propagated that narrative by reproducing the following graph of Uganda (below). To be sure, retrospectively, the chart documents the cumulative progress of one of the stars of emerging Africa well. Dercon is glowing of the small and medium enterprises he visited and particularly their dispersion throughout the country, the linchpin of the Ugandan growth model. I once attended a LSE-in-Beijing lecture of a London business school professor who conducted an expensive research program in Uganda assigning many of these SME business owners with developed world + China (the Spain part) mentors instructed to provide firms with knowledge of best practices.

The retrospective documentation neglects the subjective experience of how development is experienced by individual elites, particularly those elites who must hand power to finance ministers to achieve it. In individual years, the developmental bargain may even appear totally jeopardized. Especially those countries starting from a very low bar—in 1986, Uganda was among the least complex countries in Hausmann’s dataset—the sense that development is a gamble is often heightened, no matter how much technocratic expertise might insist on a recipe.1 Here is another version of the same chart. The trend is clear, but remember practitioners do not have foreknowledge of the trend, and in fact lack information of even incoming data. Policy is conducted in the dark.

In the previous chart, note the very strong relation between expanding the quantity of products where Uganda is an effective exporter and the economic complexity index. There is one notable exception, which is the explosion of products from 1993-1994. It is helpful to zoom in on those years as it represents a common kind of exuberant expansion. The expansion is primarily into products that are less complex, and cannot be sustained, leading to a hangover-like complexity stagnation, the long-run determinant of growth. Uganda wouldn’t reliably cross the 1993 ECI level for another decade.

Of the 30 products that entered the product space in 1994, they were almost exclusively in primary products with only a handful in the upper half of the SITC classification, offering the best opportunities for upgrading. Notably, in spite of the big push expansion, the median product complexity declined. The modest totals in basic machinery and agricultural chemicals categories are still significant to note as it left traces for future development. Hirschman would call it possibilism. The Chinese poet, Lu Xun, has a famous poem articulating the same message.

Bangladesh is even more difficult to make the Quiet Revolution case for, because for the entire period from 1988-1994, it was moving sideways (see figure below). On closer inspection, as Mujeri and Mujeri argue in their book, even in the 1980’s when it had not yet shed its “basket case” reputation, they were making quiet micro-macro alignment steps that would foreshadow future development. Unfortunately, that future development would have limited returns. Even in spite of its growth performance, today, Bangladesh’s complexity, the structure of its production, is below that of Uganda. Tragically, Tooze wrote in a recent Chartbook, the South Asian polycrisis edition, in the shadow of coming climate catastrophe, the story of Bangladesh’s future development isn’t so much the possibilism of prior development trajectories, but the catastrophism of navigating life amidst capitalist ruins.

Structural Transformation is Graded on a Curve—Like a Bellows (1995-2005)

In Bangladesh, the future began in 1995. In that year, the country supplemented many of the core competencies in the garment industry, including baskets, shoes, bicycles, and lighting fixtures (see figure). But similar to the efflorescence of Uganda in 1994, this exuberant diversification was not to last, returning back down to those core competencies such that 8 years later the product space was, if anything, more concentrated in the bread and butter of the textile industry. As was also true in Uganda, the country broke through the product ceiling toward the end of the period, albeit with a lower resulting complexity gain relative to expected gain at the beginning of the period with a similarly constructed product space.

Bangladesh is particularly striking because in spite of the distribution of production statistics being broadly similar for 1988 and 2003, economic complexity was much lower in 2003 because of the ubiquity of the products under its sphere of competence. Development and export promotion strategies are perhaps one of the most fertile sources of lesson drawing and copycat nations lagging behind seeking to develop the same competencies invariably follow. I quoted one of my grandfather’s favorite lines in a recent post on falling investment rates in the developed core. It seems just as appropriate to repeat for nurturing emerging industries in the developing world, “Always remember you are either moving forward or backward. In this world we live in, staying in place isn’t an option. This is as true for individuals as nations.”

Starting from a lower base, a country that did significantly better in the Red Queen race was Uganda. Recall the few lines of products I emphasized from their 1994 expansion? It turned into this by 2005, a favorable structure of production for a scale economy foundation. However, the volumes were lacking to be a significant driver of growth in 2005.

2005-06 is End of the Long 20th Century

I have a few different answers for why I believe 2005/06 to be the end of the Long 20th Century. Tooze would say that it is approximately the moment when American power ceased to defy gravity. I think more persuasive still is that the productivity surge beginning in 1995 proved to be temporary running into bottlenecks. The efflorescences of the developing world were thematically similar in that both were crises of success, but the timing of both is surely a coincidence.

On the other hand, Stephen Roach, then an investment head at MorganStanley, but is still around and has an important book out this fall, offers an interesting perspective in a 2006 special issue of The Economist on emerging markets. Their weaknesses had fundamentally changed from the dramatic set of the Asian Financial Crisis emanating not from external financing but external demand. In another piece, the economics editor, Pam Woodall, emphasized another milestone that on PPP terms the amalgam of “emerging markets”, which Dercon emphasizes share nothing in common encompassing growing, stagnating, and purely dysfunctional basket cases like the DRC, had surpassed their rich world neighbors in the Global North that year. I hope that I did justice to that amorphous indeterminacy here, as I am certain about nearly nothing when I transiently reflect on these nations, dropping in as a passerby. Still, I have enough certainty to make a pledge: if I ever take Delong up on his invitation to write the history I’d like to read, it will be embarrassingly derivative of Gerstle, The Ten Thousand Neoliberal Orders: A History of the (Very?) Short 21st Century (2006-). The one-word chapter titles will also be derivative of Gerstle, concluding with Harmony 和谐.

If any of you think this is nonsense, I listed off reams of industrial classification product codes to demonstrate that there is no scarcity of data, only attention of folks committed enough to critically analyze it. My Twitter profile was modified recently for a reason: that since one person alone is never sufficient, it is necessary to adopt the observations of others to clarify that which fits better.

It seems that one person has accepted Delong’s invitation, and is already engaged in spinning a narrative, adopting those observations as viewed from the ground rather than by spreadsheet…..

For very poor countries, there is a recipe that is harder than it sounds. Stop doing bad things, start doing good things. After moments of upheaval, vicious cycles notwithstanding, sometimes people tire of doing bad things. Dercon writes in a very important passage on pg. 63, reviewing the literature on systemic vulnerability, “[the developmental bargain] is also consistent with emerging research that shows that conflict may encourage cooperative behavior at various levels of society and so the emergence of new forms of cooperation between the elite may well be possible.”