“When in danger, the sea-serpent divides itself in two./ One self it surrends for devouring by the world/ with the second, it makes good its escape…In the middle of its body there opens up a chasm/ with two shores that are immediately alien….To die as much as needed without going too far/ To grow back as much as needed from the remnants that survive…non omnis moriar…The chasm does not cut us in two.

The chasm surrounds us,” my butchered excerpt of Polish poet, Wislawa Szymborska’s poem, titled “Autotomy” (not, Autonomy!). For the full poem, this essay is a good interpretative post of my preferred translation (i.e. “chasm”, not “abyss”).1

“The strongest is never strong enough to be always the master, unless he transforms strength into right, and obedience into duty,” Jean Jacques Rousseau.

“There is an alternative line of assumption…[the historian] comes to his labours conscious of the fact that he is trying to understand the past for the sake of the past, and though it is true that he can never entirely abstract himself from his own age, it is nonetheless certain that this consciousness of his purpose is a very different one from that of the Whig historian, who tells himself that he is studying the past for the sake of the present. Real historical understanding is not achieved by subordinating the past to the present, but rather by making the past our present,” Herbert Butterfield.

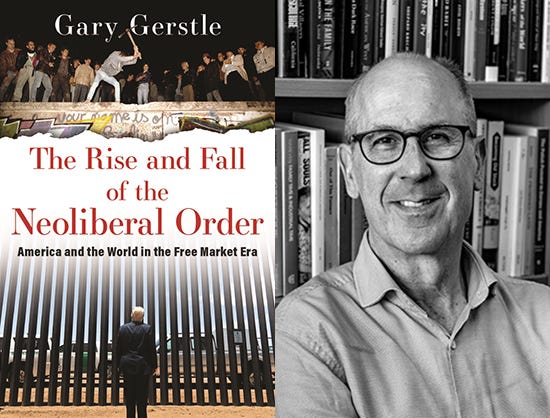

I had procrastined on typing up my thoughts on Fritz Bartel’s masterful epic, The Triumph of Broken Promises, on the shared ideological vision in East and West that emerged in the 1970’s to meet the governing challenge brought on by the first oil shock. Brad Delong’s post two days ago on a related book, Gary Gerstle’s The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order, made me realize that perhaps I shouldn’t have been so hesitant. Sometimes, we may find that bits of understanding can come from what you initially considered to be only a jumbled collection of notes, scribbles that “are not ready for primetime”. Albert Hirschman articulated it best in the Principle of the Hiding Hand, in that we consistently underestimate the creative resources between our ears until we trick our minds into overcoming the hurdle involved in deploying them.2 So this is my attempt to observe the Hiding Hand Principle. I have a feeling that, like Delong, I will sail past the desired word count. That is the side effect of having a hidden hand. Still, I will do my best to keep this post structured around the three quotes above, reviewing in turn, the relevance of the autotomy idea to global political economy, the failure of pluralizing magic transforming power in the Soviet Union, and, finally, a meditation on what Bartels intended by the final line, “It is the question that defines our time.” In what sense is the past our present?

Autotomy: Epic Confrontation Only Option when the Chasm Surrounds

The author of the most epic Slaughterhouse5-style Twitter threads, Tim Sahay, once asked THE question of history seminars have obsessed over for decades: did history end in 1989 or did it begin in 1979? Humans, being creatures that happen to have ten fingers, are more likely to spin narratives where the historical hinges are separated by precisely ten years. I am an offender, as I frequently draw emphasis to two years, 1995 and 2005.

Interestingly, both periods can be viewed oppositionally as moments of strategic opportunity, with the effort to channel the second oil shock and bust into squeezing the Soviet Union succeeding, and the ICT-led efforts to spur a revolution in general purpose technologies stalling. The latter failure can still be revived, as many recent books have noted, from The Great Rupture to The Exponential Age to a book that caught my eye while browsing, Sebastian Mallaby’s The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future. If there is a single lesson to be gleaned from big history, it is that it is littered with “successful failures”, those failures which nonetheless laid the foundation for future success.

Gary Gerstle, the diligent historian, places so much emphasis on this ten-year period, reviewing issues of Wired magazine in droves, because it was a moment of contingency. Many alternative futures were forged, and most perished as soon as they came out of the furnace. But the process suggests there is no rigid reflexivity of Berlin Wall crashing down, leading to hubristic belief that all barriers should be removed, incubating an absurdly theatrical nemesis of ethnonationalist walled politics with Trump as the vanguard.

Contingency is one way to complicate that narrative. If Clinton had taken a firmer stand against right-neoliberalism in his second term and insisted on shoring up a version of the neoliberal order that exclusively favored its left adherents, today we’d be on firmer ground. Clinton played cozy and, imperceptibly at first but unmistakenably in retrospect, right-neoliberalism invaded the host. Left-neoliberals reckon with the damage, and must consider a range of operations, politically as well as economically.

All of the operations share one procedure in common: autotomy, to remove the debilitating part for devouring by the world while leaving the healthy part alone. Treating the political crisis, the procedure is experimental with no track record of success. It is the kind of procedure a patient gets backed into when the diagnosis is already terminal. Damon Linkler made a vital point last week on how lawyer brain can lead to magical thinking. Rule of law matters little when trust has unravelled to the point that one of two political parties will dedicate itself to sabatoging it. Others are more sanguine. After all, left-neoliberal expertise can take from their adversaries’ playbook and invade the new host in like fashion, reversing GOP hegemony.3 If they can stomach the ethnonationalist doofuses they would be forced to call colleagues, the upshot would be to avoid the risky procedure.

Economically, autotomy is in the spirit of my provocative claim, We are All Jeffersonians Now. I should clarify. There is nothing inherently satisfying about the idea of abandonment, of immoderate greatness, to the point that it would gain traction in such disparate corners of the political spectrum. In the age of climate breakdown, soon to merit capitalization, the Hamiltonian role of the financial system is more, not less vital. A brilliant group of green finance experts, headlined by the Gabor Girls and Kedward’s Keynesians, recently summarized the logic of a National Investment Authority (NIA) in that green innovation cannot be incubated in geographically fragmented and temporally ephermal agents who lack the cohesion of a Eurodollar type anchor. Hockett, in his latest, The Citizen Ledger, similarly flips the Jeffersonian/Hayekian sensibility on its head, “agents who act in the name of spatially and temporally extented commercial republics as wholes…not spationally fragmented and temporally ephermal private agents [opting to speculate in metamarkets].” Simply ending private credit generation for crypto boondoogles without public generation for the Green Industrial Complex would be profoundly deflationary. And with the expected political reprecussion of boot stamping to follow.

In other words, the proponents of narrow banking, most notably, Mervyn King in The End of Alchemy, follow other forms of establishment liberalism in that they are too timid. Robert Frost once quipped that the way to distinguish a good liberal is that he refuses to take his own side in a quarrel. Amidst a capital glut like the world has never seen, many folks who genuinely believe themselves to be reformers serve the ends of the cynics. No, answering the call to climate breakdown requires confronting only that which needs to be confronted and no more. Critically, it is not a Trojan Horse for those disaffected members of society, chiefly milennials, who have received so little benefit from a battered social contract they’d rather upend it.

The task is to specify in detail what investment is to be promoted and to begin penalizing those activities, both on the energy and capital markets side of the ledger, which outght to be penalized. The Gabor and Kedward brief outlines the logic of protracted confrontation with credit allocation policies meeting conditionality dovetailing with Hockett’s proposals for the NIA. In part, their policy brief is the PhD level version of the textbook insight that quantity regulation is more efficient than price regulation under very high uncertainty. But as I’m sure even the authors would acknowledge, the main part is political. There exists no other way to rein in the shadow banks and the “immoral capital” particularly prevalent in the U.S. The mission is to bring the (Green) State Back In.

What does an autotomic regulation of immoral fossil capital and its abettors have to do with the Twilight Struggle, the last gasp of ideologial competition between the U.S. and Soviet Union? It relates to the ten years of transformation, a history, the conventional story tells us, that began with Volcker shock, then ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall. The actual periodization is not quite as neat, but it begins with first oil shock and ends sometime before the Berlin Wall. One ending is when Gorbachev entered stage right in 1985 as energy export earnings declined significantly, and another was in 1987 with the resulting Soviet economic policies that crystalized the new order.

There is a joke that is applied in many contexts that the PhD and completely ignorant judgments often converge. So it is with slavery as the cause of the Civil War and so it is with oil as the hidden reactant behind every major world event. The ways the energy, finance, and economic discipline components and the geopolitical, economic, and democratic stories correspond in Bartels and Thompsons’ respective narratives is similarly too neat to be a coincidence. Bartels emphasizes changes in material environment and networks of global production, energy and capital markets, without downplaying the battle of ideas outside and inside the Iron Curtain (p. 17). The schema has a rabbit-duck illusion perplexity attached to it. Splitters see many crises, a polycrisis. Lumpers see one crisis, a polycrisis.

The poltical quandaries of hyperatrophy, aristocratic privilege, and nemesis are now all upon us. Nemesis visited the Soviet Union first with the agonzing choice of disciplining citizens to acclimate to changing structure of material power, aspiring for the First World prerogative granting room to move on policy, or to abandon it, retreating from empire. They chose to perform an autotomy on empire, but the infant was stillborn.

The Crisis of Actually Existing Socialism

In my LSE notebook, I left a section at the end for books that I read at my own leisure, which, I believe, supplemented an understanding of the actually, existing world than the theoretical readings assigned to me at university. The final entries, Greta Grippner’s Capitalizing on Crisis and Layna Mosley’s Room to Move, all have interesting connections to the transformation of global political economy Bartels describes. Like recent reflections on the U.S. dollar empire from Yakov Feygin and Dominik Leusder, Grippner plays the historiographical game of pushing back the origin of the financial crisis even further back than the first oil shock, in 1968, marking the modest beginnings of mortgage backed securities. The result, the financial build-up of the 1980’s, aligns with Bartels’ narrative, “No longer would the state face seemingly impossible tradeoffs between fiscal austerity and inflation. Instead, foreign capital inflows would allow state officials to avoid difficult decisions,” (Krippner, p.104).4

The financial build-up, The Global Minotaur, was an “irrestible temptation” that Yanis Varoufakis calls the Gyges ring, borrowing from the Greek myth warning of devices that offer untethered power which ultimately enslave the appetites of the subject. At the same moment the crisis of oil export earnings was hitting the Soviet Union in 1985, capital inflows were covering all government borrowing in the U.S., totaling $221 billion. As Bartels spells out, the financial market still operated in the Newtonian realm of equal and opposite forces, triumphally in geopolitics and tragically in the domestic economy. In the U.S. and Britain, the beating heart of transatlantic financial power, the price to be paid was the erosion of living standards for the working class.

The article, Room to Move, is more bullish on the embedded liberal compromise, suggesting that the influence of the financial market is in fact deep but widely dispersed. There is no Polanyian collision course between social interventionism and the global self-correcting market but rather a virtuous cycle because international openness encourages activist investments in key areas like human capital. Tax competition does not necessarily foster a race to the neoliberal bottom because governments that choose to provide important collective goods have a cheering section within the market system itself. Tremendous cross-national variation is observed in government spending, transfer payments, public employment, and tax receipts. Because of fundamental cognitive limits, the financial market evaluates government policy according to two narrow areas, inflation and government deficits.

The significant caveat is that policy autonomy is a privilege reserved for the First World; divergence for me, convergence for thee. Most informed not expert observers are familiar with the current applications for the Third World, as the IMF abandoned its responsibilty for dollar recycling. Bartels fills in what was previously a major gap because of the perception that the Soviet Union and its satellites were an autocarkic self-contained empire, it also applies to the second world.

Krippner emphasizes that what appears as a policy “choice” was not an active decision. Transgressing foreign/domestic policy paradox by getting others to pay for the cost of empire only came about through muddling. Bartels outlines the interregnum of the 1970’s, the road not taken to the the burgeoning Eurodollar market, a global financial architecture buttressed by the IMF to manage dollar recycling. A prominent Wall Street Journal article warned of the consequences of these metamarkets in the mid-1970’s. Efforts to control subsided and growth was explosive, a harbinger of what was to come in Volcker’s controlled disintegration of the world economy, a euphemism for decontrol Volcker himself would later come to recognize.

The policy paradox dominated elsewhere. US policymakers used that to their advantage, adding finance and energy to their competitive arsenal. With Soviet Union facing the squeeze itself and unable (or unwilling in boom phases) to provide in-kind aid in form of subsidized energy, they faced a stark choice, draconian austerity or Western aid, gladly filled by commercial banks flush with cash and eager for new frontiers to park it. The instincts on which side of the bargain to take would have implications in 1989 with only Romania, the country of draconian austerity, opting for “the Chinese solution” as Gerstle imagines in “alt-Gorbachev”. Without the economy, nothing can be done. Their reasoning—efficiency is morality —had much in common with the now sidelined 80s economists who remade modern China.

As would recur in the 90s, first in Mexico then in post-collapse Russia, heuristics replace risk analysis, “countries don't go bankrupt,” the CEO of Citibank confidently asserted. In their defense, Eastern Bloc leaders played the game of assuaging rich world concerns well. Janos Fekete of the National Bank of Hungary (NBH) mimicked Deng on the uselessness of black and white cats, “[there are] no capitalist and socialist products…only good or bad machines, modern or obsolete.” They projected as much confidence as Reagan and not entirely without reason; Bartels writes with credit the good life had dawned on the Danube. The question was how long would international creditors let this vision of making promises circa 1985 last:

The answer is that, like all mirages guided by hazy heuristics, it would slip away almost as quickly as it emerged. The trigger? Again, you guessed it, oil! The other significant exporter of the bloc, the GDR, believed in its socialist exceptionalism to avoid default insolvency and, interestingly, outpace the astouding incompetence of Soviets given defense implications5 in paving a socialist Silicon Valley. They failed on both counts as collapse of oil market in 1985 turned its prized surplus into deficit territory by 1987.

This was the context to Fekete`s speech to the assembled financial elites at an IMF convening in 1986, articulating the long tragedy of global finance that persists to this day. Global capital flows are being misdirected away from urgent development tasks, locking countries in debt dependency. In a pattern now familiar to the Global South and Jubilee advocates like Ann Pettifor, debt burdens almost doubled across the Bloc in the 1980s with no capital to show for it. The problem of living on credit, many Eastern bloc leaders discovered, is you'd eventually die by it, gradually at first then suddenly.

Hemingway's insight would hit the gravitational core and periphery simultaneously. Export earnings declined just as sharply between 1985-87 in the Soviet Union as the GDR. In a moment of furious activity to compensate for delayed action, there was an effort to gain legitimacy for discipline. Peristroika and glasnost were conceived not as separate programs of economics and politics, of efficiency and stability, but a single strategy to address the now unavoidable governability crisis.

Instead, all aspects of the Hirschmanian triad, futility, perversity, and jeopardy, were summoned at once as Soviet apparchniks grappled with interest group demands without the supporting epistemological infrastructure in the resurgent Anglosphere. The Enterprise reforms of 1987 sought to impose discipline but actually flooded liquity which removed it. A soft budget constraint became no budget constraint when illiquid funds were converted in one fell swoop into cash, exacerbating runaway inflationary pressure.

Sound familiar? Whether Ophuls` insight in Immoderate Greatness: Why Civilizations Fail applies to the American case is clearly an active matter in the 'declinist' debate, but the logic of leaders turning to inflation in a nation that has exhausted other options is ironclad for the Soviet case:

Faced with deteriorating ecological, physical, social, economic, and political conditions and with declining returns on civilization's investment in complexity, even capable and honest leaders don't have a path forward...[but] something must be done, and since expediency no longer suffices, they resort to stupidity—doing what has never worked in the past, which cannot succeed in the present, and what will destroy the future...Inflation is not, the most monumental stupidity of which human beings are capable...but it best illustrates what happens when a civilization reaches an impasse.”

Combine that with the Brooks and Wohlforth paper on the material basis for the end of the Cold War emphasizing the momentous decision to liberalize FDI and 1987, neither 1989 nor the final nail in the coffin in 1991, was the year the New World Order was forged.

The Crisis Migrates to Actually Existing Capitalism

I couldn't quite decide how to answer Bartel`s final question. His mention to environmental breakdown in the final paragraph prompted me to think of the greening of the financial system. Indeed, my gut instinct is that unmitigated climate change, like uncorrected Second World largesse, will entail disciplinary costs of approximately 25-30 percent. Unprepared to accept the costs of deteriorating conditions brought on by unravelling complexity, only gradations of idiocy would be on the table. Thankfully, the American political system, its gerontocracy aside, is still more effective than the Soviet Union was on its last legs. Pure idiocy has been avoided with the passage of IRA, though with the bitter irony that it could be inflationary in the short-term as transition costs, such as minerals, will be paid up front.

More generally, I think the connection lies in the nature of Thatcher's policy advisor, James Hoskyns, the book`s central character`s stabilization program. Like all conservatives, he had a fundamental skepticism about the capacity and desire for ordinary people to act for the future. The Irish proverb, “why should I act for posterity what has it done for me,” was their motto, he believed.

Something as important as future growth prospects cannot be trusted on unruly mobs. It can only be entrusted in the high-minded stewardship of the Thatcherite clique. Reviving future growth prospects through present sacrifice was formalized in the J-curve, steering the ship of the British economy with only a little turbulence at the kink. For a while, Hoskyns was vindicated with Blair playing an analogous role to Clinton in the British political order. But the long-run capacity for action, defined according to sagacious capitalists’ confidence in investment, was severely diminished.

The direction of the investment trend in Britain is particularly disturbing, inspiring real reflection, if in some respects disappointing, from elite commentators like Martin Sandbu. Brexit has, of course, made this trend worse.

Dominik Leudsner was only half joking when he said the straight line projection of another decade of entertaining Tories’ detached fantasies that pass for leadership would be to set the scene for Gilman’s favorite movie, Children of Men.

Bartels concludes with the conception of the West, an oasis, perhaps a mirage, representing an eternal wellspring of growth. Dynamism is not automatic and never assured, my grandfather reminded me:

In advocating for a sociological grounding to restore growth, Hoskyns and other neoliberal entrepreneurs were astute. Emulating without replicating those tactics, the emerging Mutualist Order ought to focus on the Edisonian commitment to regularized trial and error investment. And greatly reduce the reliance on fickle disruptive “innovation” favored by Tesla, currently reified in the high modernist moment. Failing that, citizens of the First World, too, will join in on nemesis.

By prefer, I mean that I prefer the image of lateral division rather than fixate on the depth below, as I obviously have no authority to select which translation more accurately conveys her intent. Readers who subscribed last December may remember that I used the word “chasm” to describe the planetary impasse in my 12 tweets essay. Another time I invoked the image was in a summary essay, reflecting on my visit with President Carter on US-Sino relations, “Man is rope stretched between animal and Superman, a rope over the abyss.” The implication of autotomy is leaders of both nations must look in front of them, and cooperate on issues of in the surrounding chasm of strategic priorities, and, in so doing, will have shed those animalistic instincts.

My mother tells me of her Uncle Jarley, who once upon a time used to walk tightropes attached to the Empire State Building. He intuitively knew that it never behooves you to look down on the abyss that hangs below. Better to keep your attention focused on two outstretched points, and, in fact, can only be bridged with your sustained focus. A similarly impressive daredevil who perhaps offers an even better metaphor attended my high school, the freesolist, Alex Honnold. A classmate asked the inevitable question, which he answered patiently: Do you ever think about falling? And a follow-up: What kind of tick do you possess that prevents you from thinking of falling? He told the audience he spends so much time thinking of every nook and crevice on the rock in his trial runs, that the main event is largely executed subconsciously—he treats the permutations of potential climbs on El Capitan largely as a chess grandmaster approaches his board. Still, I’m wondering what exactly is the climatic equivalent of the “leap”, solving the seemingly unbridgable climbing problems of El Cap he performs in his documentary, Free Solo. Perhaps, it is this, from the Chapter titled, Focus, in Gal Beckerman’s wonderful history of intellectual and activist protest movements, “the abscense of embellishment feels [as if] is a creative act—sharpened the focus.”

The link to the essay on Hirschman was written by Malcolm Gladwell. He has been getting dunked on recently after a glib comment on WFH reported in The New York Post, “what have your lives been reduced to.” I should perhaps know when to exercise restraint to not pile on in a Twitter mob, but couldn’t help myself, coincidentally responding to something Delong had written at his old blog on Enron criticizing Gladwell’s trademarked “contrarian” style so adored by the liberal establishment.

Some readers might ask, what GOP hegemony? They are already backing themselves into a corner with extreme positions and candidates that don’t even speak to the appeal of the GOP base. Nate Silver’s recent polling suggests issues like abortion have moved the needle. I saw a viral Tweet that disappeared into Twitterverse, hoping for this to be true, but don’t know how to evaluate against more likely prospect that there is a polling crisis in the U.S.

And her conclusion aligns with Hockett on the artificial scarcity that quiet revolution would perpetuate, recycling Daniel Bell on the infrastructural power of finance, “Novel forms of organizing the economy would pose new forms of scarcity.” Enter the primary character of Makers and Takers, Jack Welch, the paragon of American business in the age of deconrol, eschewing engineering expertise for clever financial engineering.

Power, Globalization, and the End of the Cold War reads as an incredibly loud echo to strategic competition with China, especially the diverging estimates between Soviet bulls, highlighting rapid catch-up growth, and bears, emphasizing transition barriers. The difference was of slope. Bears had even higher rates of growth during extensive phase than bulls, but claimed the bulls underestimate how quickly extensive opportunities will be exhausted, producing much lower growth estimates in the “Twilight” period.

Another loud echo~ Don't lag in microelectronics as that shortfall could spell doom for military balance.