The Chinese Struggle between Land and Sea Power

An Interpretation of Dan Wang's 2021 Annual Letter

“Demography is destiny.”

“Power in repose is power in decline.”

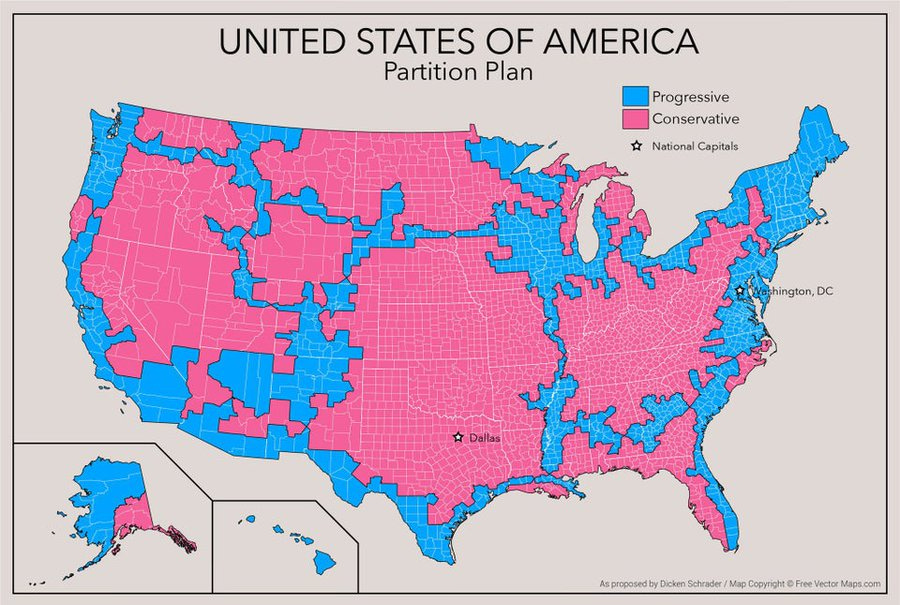

Recently, I encountered this chart partitioning the United States into progressive and conservative camps. It represents young Obama’s worst fear, a Red and Blue America.

This chart piqued my interest as I was doom-scrolling Twitter, because it aligns with my interpretation of the political struggle in the U.S. as a classical conflict between reactionary land power and liberal sea power. The journalist James Fallows pointed out that reactionary land power is even more secluded than this chart suggests. In the battle for public opinion, even Dallas is firmly on the side of the Progressives, favoring Democrats in all recent Presidential elections. Alternatively, Dallas could also be viewed as the natural choice if the principal cleavage in American society is not so much land versus sea power but competing factions for and against fossil capital, as Tooze wrote in Foreign Policy. If the American fossil fuel oligarchs had to select a single big city in America as an outpost, they would likely carve out an enclave within Dallas.

As I was reading through Dan Wang’s 2021 annual letter on the differences he observed in China’s three mega-regions centered around Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou/Shenzhen, I had a similar thought as it relates to the struggle between reactionary land power and liberal sea power. The political elites in Beijing have carved out an enclave for themselves in zhongnanhai in much the same way as Republican dark money oligarchs in Highland Park. Wang’s description of the quality of intellectual life as a redeeming quality for a brutalist city built for military parades resonated. When a boss returned from Beijing after Xi Jinping became President for life, I recall that he was struck by the criticism he encountered. Among the articles they discussed in private over dinner was a polemic written by a former Party School professor, Cai Xia, titled “his” madness. David Shambaugh’s recent book similarly writes of pervasive intellectual groveling as it relates to Xi’s concentration of power.

To be sure, this intellectual groveling is contained to ensure this outer-inner opinion does not extend to either edge of public opinion, inner opinion (as in the case of Cai Xia’s excommunication from the Party) or outer opinion. The loudest of these dissidents in Beijing are “vacationed”, one of the bizarre Kafkaesque displays of state power Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker on the bei luyou phenomenon. But perhaps, more revealingly, the urban geography of Beijing does a lot of the heavy lifting for the Party-state. The inner-wall neighborhoods in central Beijing are the playgrounds for the political elites, the Chaoyang area in eastern Beijing is the Central Business District where the business and diplomatic elites reside, and the Haidian area in northwestern Beijing are set aside for the tech and intellectual elites. Under the broadest strokes, the first group intends to pave a narrative of the future firmly grounded in the Party’s past, the second group is too busy with the present, while the last group crafts a different narrative that China’s future, or grand rejuvenation, rests on breaking with the past. This was Cai Xia’s ambition to articulate a vision of democracy as an escape from the inexorable devolution toward dictatorship.

These surprisingly cosmopolitan pockets of intellectual activity are the basis for why one of the most well-respected China scholars, Orville Schell, confidently asserts that China is “a once and future democracy.” The irony is that these pockets are most active squarely within the belly of the beast of reactionary land power. An educated but uninformed observer might expect for these pockets to find a better niche in Shanghai or Shenzhen. They might say that geographically, China has more in common with a country like the U.S., where the major population centers are along the coasts, with very folks on each continental power residing in the far West than it does with an archetypal despotism like Russia. And for this reason, with urbanization and modernization, you might expect the center of power to shift away from Beijing toward the big coastal cities. Self-obsolescing modernization is not so much observed in the income statistics as in bigger geographic shifts. For a while, this appeared to be the story that played out. Factional politics between the Chinese leaders were initially dominated by the Revolutionary Guard in Beijing, shifted to Jiang Zemin’s Shanghai faction during the second period of Reform, then a backlash came in the form Hu’s elevation of rural and Western concerns. President Xi, who unlike Hu did not rise up in the Party hierarchy through peripheral Western provinces, nonetheless reaches for Hu’s critique of unbalanced regional development in his own vision of common prosperity.

The reality is a bit more complicated because, save for what you might hear about northern stagnation relative to the dynamic capitalist South, urbanization has been remarkably uniform across all major Chinese cities. China watchers know the story of Shenzhen’s meteoric rise from fishing village to technology metropolis well. They might also know the demolition of Shanghai to the point that the urban landscape appears to temporary visitors as in a state of constant transformation, perpetually unfamiliar. What they likely don’t know is that the relatively stagnant cities like Beijing and Tianjin have also undergone unprecedented waves of urbanization. Compare the bicycle Beijing my grandparents visited in 1993 with the same city I visited 25 years later. My PKU urbanization professor took the entire class to a museum directly south of Tiananmen documenting this remarkable transformation of an ancient city of alleyways built for foreign steepe invaders. Sub out hutongs for shikumen and you will hear a very similar story if you visit the museum’s counterpart in Shanghai, on the north end of People’s Square.

However, these urbanization trends toward greater economic and social complexity do not hold for all of Greater China. Wang’s view of Hong Kong as the demise of a stagnating city-state that has lost its cherished independence, and more recently, on a path of absolute decline as it hemorrhages an exodus of talent are all correct. The situation in the Northeast and water scarce West is even more dire.

Taking Dan Wang’s regional division as a starting point, I intend to illustrate in this post that Shenzhen is perhaps an extreme example of a general phenomenon. I will look at six cities, two in the North, two in the center, and two in the south. Interestingly, the data buckets, retrieved from the European Commission’s Global Human Settlement Layer (GHS), for each of these regions are oriented in ways that suggest a simple division of land and sea power. Beijing is faced toward the northern bread basket, while both of the southern megaregions are oriented toward the sea. The two cities I selected in each region are Beijing and Tianjin, Shanghai and Hangzhou, and Guangzhou and Shenzhen.

Analysis

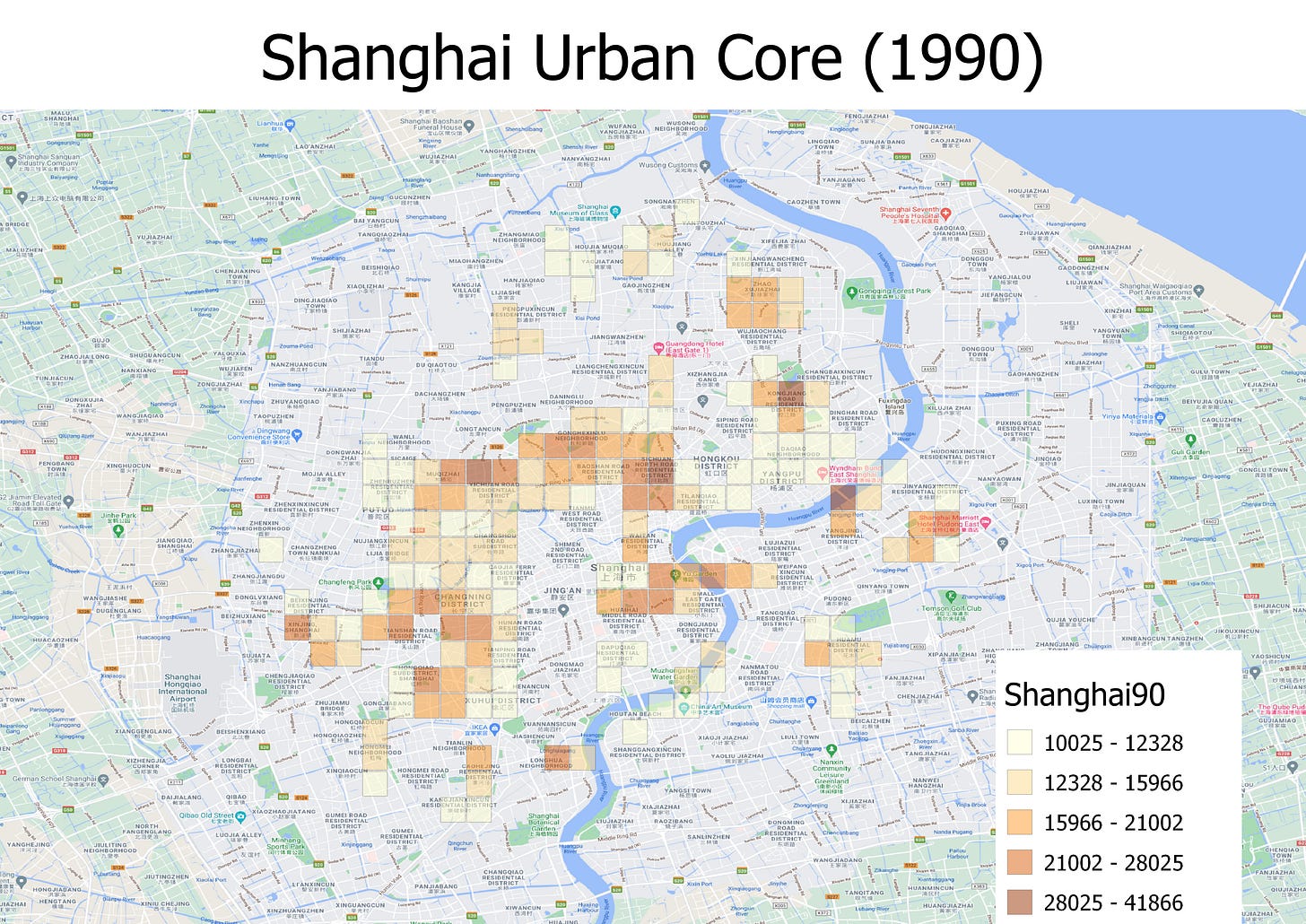

From the European Commission website, I isolated the cells, approximately one square kilometer each, that contain at least 10,000 people for both 1990 and 2015, and demonstrated the differences through the built-up growth of high density areas. The legend colors indicate the range for the number of people in that cell. Beijing was obviously already an established city in 1990, as even my grandparents were blown away by the hordes of bicycles they observed. But the city “only” had approximately seven million residents, and followed an exponential growth path to 2010, slowed a bit after that hitting a population of 18.4 million in 2015. It is hard to emphasize how spectacular that growth is, but comparing the maps side by side gives the reader a sense of the scale of the project.

As we will see with the other maps, Beijing urban planners have not completely shed its rapidly disappearing hutong heritage as the city is still significantly less dense than many other Chinese cities (Note the upper limit). In 1990, there were really only a few pockets of dense areas in Haidian near the elite university cluster and in the Fengtai suburban district in working class Beijing. The central business district located in the east sprouted out of nowhere, and entire areas in Xicheng directly west of Tiananmen and Shangdi outside the fifth ring road were completely filled in. At around the same time these regions were developed, building a fortune for real estate tycoons involved in demolishing the old city, the Western consumer economy started to appear. As Shambaugh recalls in his book, a large crowd gathered at one of the first department stores over the sight of a washing machine!

A similar story played out in Tianjin. The city is often paired with Beijing, as the Communist heritage is also present in the city’s architecture. Tianjin might not be used as often for military parades, but with all its large central squares and boulevards, you would be forgiven if you thought you were in Moscow. The city tripled its population in 15 years to just over 12 million people.

Unlike Beijing, the city simply absorbed more people in the areas that were already dense, rather than transformed into something wholly unfamiliar. Still, the urban core roughly doubled in size expanding to the northeast corner.

Now onto central China:

I included Hangzhou as the city to pair with Shanghai over many worthy candidates in the extremely wealthy provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangsu because of how captivated I was by the wealth flowing through the city during my brief daytrip in 2015. The e-commerce giant, Alibaba, is located there. When I was stuck in traffic with our cab driver (who we had difficulty negotiating a rate), I remember staring at the Ferrari and Lamborghini dealerships that lined West Lake. There was a kind of Gatsbyesque beauty in staring out across the lake in the hazy fog. But the message was clear and no doubt internalized by the city’s technology industry working tirelessly to get to global parity. To get rich is glorious.

Hangzhou’s growth followed a similar patter as Tianjin, absorbing even more people in the already built-up regions, while expanding out into the northeastern edges of the city. Growth in other directions was limited by the natural barrier of West Lake.

The growth of Shanghai is more similar to Beijing as its lack of density in certain areas is also related to foreign interlocuters, though they did not come from the steppe. The empty spot in the first map south of the Jingan Temple in the heart of Puxi? That aligns with the residential areas of the former French concession. Northern Shanghai near Fudan University, where I attended in 2015, wasn’t really developed yet, except for Wujiaochang, the isolated block of six cells in the northwest corner, which changed to the darkest shade in the 2015 map.

The Shanghai equivalent of the central business district is the famed Pudong skyline. A visual might add to the above maps. Again, like the CBD, it sprouted out of the ground, followed by the development of the consumer economy. When I visited Pudong in 2019, I made a point of trying Chinese Taco Bell, which has been revamped since the previous time it was introduced to the Chinese market and is now quite popular amidst a brutal Shanghai restaurant scene.

Now time to settle the eternal friendly dispute. 北方还是南方好?

Shenzhen does indeed top all Chinese cities in terms of population growth, as this helpful little list by The Guardian found. The interesting thing about its exponential growth is that in the period from 1980-90 rising out of obscurity, the seeds of its future growth were already laid. There were already noticeable clusters in the city center and at three distinct edges. Their project was simply a matter of connecting and filling them out.

However, this map actually understates just how miraculous the growth of this region has been over the period observed here. Of the top ten cities highlighted by The Guardian, neighboring Dongguan is number two and nearby Huizhou is number seven. In that entire metro area, less than a million people resided in 1990, now more than 20 million call one of these three places home.

With the outlines of the urban core established in 1990, I had assumed that population growth in Guangzhou would be the most modest relative to other cities I observed. I would be wrong. The population exploded to 8 million in 2000, then slowed to 12 million by 2015. Growth of the built-up area certainly played a role, as Guangzhou followed a twin-cities pattern of urban expansion with neighboring Foshan to its southwest. But the density was arguably more decisive, as the dark brown part of the map is among the most dense organized human settlements on earth.

I would like another chance to visit southern China, as I almost neglected it entirely. As an American accustomed to suburbia, there is a lot to learn from the other ways of living density allows. And it doesn’t imply Soviet apartment blocks or unorganized slums the single-housing family lobby in the U.S. often invoke as scare tactics. After all, Paris is a perfectly nice place to live. In a reversal of history, I think Americans have a lot to learn from the strategy of enhancing productivity through urbanization from the Chinese. With our higher base of human capital, I think even more could be gained from the chance encounters that make density so desirable. Density of course does not guarantee interaction. that is why the model is Paris not Moscow. But they are more likely to occur in the liveliness —I believe the Chinese call it renao— of public spaces. The first priority is tackling the housing crisis, so the marginal person who wishes to live in a city does not feel compelled to live in a suburb (or even worse, stuck in their parent’s suburban home) simply because the cost is too great of a barrier.

At least as far as population is concerned, the conclusion from this analysis is that the northern stagnant/ southern dynamic with Greater Shanghai paving its own independent course somewhere in between is a caricature. Urban growth has been substantial almost everywhere, with few exceptions, and we can therefore expect the modernization process to be observed more uniformly. This includes intellectual groveling in Beijing about Xi Jinping’s imperial presidency. Nonetheless, the story of China’s governance is not of stagnant decline as Beijingers twiddle their thumbs as real power shifts elsewhere. Demography is destiny, but it is not the kind of dramatic destiny implied by a tectonic shift. In keeping with China’s imperial mythology, absent an earthquake we have no reason to expect, there will be no dynastic change of the guard. Instead, the very real challenges of China’s demography relate to how policymakers can sustain growth when it has already exhausted the gains to be had from urbanization, and the demographic dividend has evaporated. On both counts, China is past a crossroads, and at a stage where improvisational crisis management is the only recourse. China, like America, will remain a people of paradox, split between the conflicting mandate of managing a sea and land power, an impossible task we are both condemned to perform.