2005: When Things Fell Apart?

Revisiting The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth by Ben Friedman

“In my opinion, the defining trait of a superpower is not its weapons systems, strength of its currency, or how widely its language is used, but if it promotes peace and human rights in the world,” Jimmy Carter.

I will confess that this post is a bit more harebrained than usual. But I have been noticing that my evidence gathering to periscope the rage percolating within American society is a bit like a mad detective posting newspaper clippings on a bulletin board. They all point to one year—2005. I do not know why this year recurs with such consistency, so I suppose it could be said the suspect is still at large. But the observation led me to a flawed but admirable book, The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth by Ben Friedman.

I am in broad agreement with Joseph Stiglitz’s critique of the book when it was released in 2005. The book’s flaws are mostly related to its age. The absurd deficit hawkishness of the book, lauding Clinton economic reforms as causal to uptick in productivity growth of mid 90’s, is particularly salient. Even as sections of the book read like a primary source document, there are others that are uncannily familiar. Take this excerpt on the passage of the 1993 budget package:

It was, and remains, the only piece of major legislation to be passed in recent memory without a single vote in favor from the opposition party in one or another house of Congress. All 41 Republican Senators were opposed.

In other words, the Clinton budget birthed the Party of No. Friedman accurately recognized the stakes of what was occurring, but goes further that the illiberal turn away from openness, toleration, mobility—democracy without democrats—was fundamentally a crisis of growth:

Even in America, I believe, the quality of our democracy—more fundamentally, the moral character of American society—is similarly at risk. The central economic question for the United States at the outset of the 21st century is whether the nation in the generation ahead will again achieve increasing prosperity, as the decades immediately following WWII, or lapse back into the stagnation of living standards for the majority of our citizens…merely being rich is no bar to a society’s retreat into rigidity and intolerance once enough of its citizens lose the sense that they are getting ahead.

He was proposing that a lot of the thinking from liberal lions of the Bush era on the moral erosion of the American fabric was in fact backwards. To be sure, from a pure political/rhetorical perspective, it makes perfect sense to take President Carter’s view in Our Endangered Values, written in the same year, that problems like economic inequality or political corruption can only be corrected by addressing the fundamental moral neglect. Carter and others hoped that they could forge a rallying cry that would inspire a sufficient groundswell of public action. In a sense, they succeeded. 2006 was a good year for Democrats.

Yet there is something perverse to merely evangelize against a backdrop of growing precarity and stagnation. The most remarkable thing about this book is that he did not yet have the evidence, but his predictions were ultimately borne out on both counts. There was a return, and in fact a further slide down, the stagnation that characterized the 1970’s such that the TFP growth of the booming 90’s proved only temporary. Neo-feudalism, along the lines long theorized by Robert Brenner, saw a resurgence. And there has been an equally stark decline in democratic indicators to the point that the U.S. starred in a global drama of democratic recession.

The first chart on productivity is from economist Robert Gordon’s necessary complement to this book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth. Note how sharp the decline was in labor productivity after 2004. Friedman was not alone in believing that the economy had already exhausted the low hanging fruit of the IT revolutions, and would be forced to shift to debt-fueled consumption of the housing bubble, but still exercised remarkable foresight.

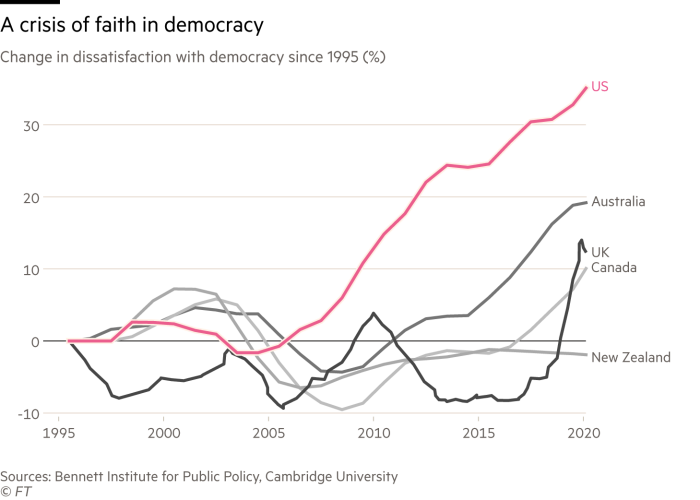

The second chart on politics can be found in a masterful column by Martin Wolf in the FT. In contrast with many other democracies in the Anglo-American world, democratic rupture in the U.S. has been long in the making, an insight also explored in Evan Osno’s recent book, Wildland. When did Americans begin to lose faith in democracy, according to surveys? Around 2005.

The international dimension is the most neglected in the book, but again, it points to 2005. The preeminent authority on the Chinese economy, Barry Naughton, points to 2005 as the turning point of China’s imbalanced investment-led growth. In the same year, then provincial Governor of Zhejiang Xi Jinping delivered a speech (link in Chinese) warning of the dangers of relying on that model. Since that style of Gerschenkronian development has always been followed by substantial industrial emissions, it should come as no surprise that China surpassed the U.S. in 2005.

The precise year of these policy choices is surely a coincidence. However, economic theory would predict that if productivity gains have been proven to be exhausted domestically and there is a very large scarce capital, abundant labor country (remember Heckscher–Ohlin?) that recently entered the WTO and eager to attract FDI, that the chosen strategy of most players would be to integrate that economy to their global value chains.

The integration proved to be a boon to the economy as an abstraction, but often disruptive to how people experience the economy, as even the neoliberal cheerleaders like Krugman later admitted. In this environment, there is a political double movement where the embedded public resists the idea of the economy as an abstraction. This resistance is populated by a spectrum from Marxist historians like David Harvey to reform-minded technocrats like Stiglitz, channeling RFK’s famous line, that growth ought to measure what actually matters in people’s lives.

For the most part, I disagree with the prescriptions offered, but that is not to discount the predictive insight of his thesis. It can be summarized by the simple formulation: growth is moral, so to be degrowth or agrowth is to be immoral and amoral. Reflecting the different era of the early aughts, Friedman was addressing the anti-globalization movement, but it could be read as a powerful antidote to the degrowth movement sparked by groups like Extinction Rebellion:

Further, even when people plainly acknowledge that more is more, less is less, and more is better, economic growth rarely means simply more. The dynamic process that allows living standards to rise brings other changes as well. More is more, but more is also different. The qualitative changes that accompany economic growth.

Even as the economics profession is increasing forced to concede the condition of monotonicity, in a world where emissions stubbornly rise with growth (though not per unit of output, as Friedman writes), the degrowthers charge that this qualitative revision represents wishful thinking. Stiglitz and other reformists are more receptive, arguing that the project to reassess growth in the Exponential Age is one that accounts for qualitative changes. Both critics—what Keynes would have called the outside opinion and inner outside opinion—of orthodox economics emphasize the accumulation of risks. Just as no self-respecting investment analyst can reliably forecast without the balance sheet, no self-respecting macroeconomist can assess risk without referencing the analogue “balance sheet” of both social and natural capital.

The critical choice is not between degrowth and unabated emissions. Radical degrowth of the kind that no climatic regime could possibly administer would only slow the course to catastrophe. And, in the meantime, the social settlement would prove untenable, especially globally as Branko Milanovic has emphasized. Neither racing over the abyss of fossil capitalism nor returning to the romanticism of some Enlightenment philosophers strikes me as rational. Both are equally disengaged with reality.

The choice is just as Friedman perceptively argued in 2005. Will Americans spur a global investment drive to ignite the next wave of GPT’s? We are out to prove Robert Gordon’s contention that the economic revolution associated with electricity and the internal combustion engine between 1870-1970 was unique and unrepeatable. That would mean leaning into the potential of a whole new wave of GPT’s from biology to manufacturing that can not only allow Americans escape the malaise of 70’s style stagnation but also the planetary impasse. Both the social and economic goals and the planetary aims can be achieved if that investment is made to be an integral rather than transitory part of Keynes` Agenda.1

In regards to GPT`s, the only rational course was set forth by Bertrand Russell. How do we adopt the scientific method, while also refraining from perverting it so as to adopt a mechanistic outlook on the world, pursuing false idols? This is a delicate but necessary balance. Russell's wisdom will likely be as neglected in 2021 as it was when he first articulated that balance a century prior.

Keynes wrote in The End of Laissez Faire (1926), “We cannot, therefore, settle on abstract grounds, but must handle on its merits in detail, what Burke termed ‘one of the finest problems in legislation, namely, to determine what the State ought to take upon itself to direct by the public wisdom, and what it ought to leave, with as little interference as possible, to individual exertion’…Perhaps the chief task of Economists at this hour is to distinguish afresh the Agenda of Government from the Non-Agenda; and the companion task of Politics is to devise forms of Government within a Democracy which shall be capable of accomplishing the Agenda.”