“The real trouble of this world of ours is not that it is an unreasonable world, nor even that it is a reasonable one. The commonest kind of trouble is that it is nearly reasonable, but not quite. Life is not an illogicality; yet it is a trap for logicians. It looks just a little more mathematical and regular than it is: its exactitude is obvious, but its inexactitude is hidden; its wildness lies in wait,” G.K. Chesterton.

The other day I had a good conversation with a friend, who was helping me get my badly injured ankle checked out by the doctor. In the the course of that conversation, he said something that piqued my interest about investing sage and Warren Buffet’s business partner, Charlie Munger. Everybody who has worked with Munger says they are not quite sure where his investing insights come from, he told me.

In a famous 1984 essay, Buffet characterizes men like Munger as possessing a talent that cannot be cultivated, noting “it is not a matter of IQ or academic training. It’s instant recognition, its nothing.” At annual investor gatherings, Munger emphasizes investing remains more art than science, no matter how many math PhD’s are hired to work for outfits like Renaissance that attempt to time the animal spirits as a study of complexity dynamics. These wickedly smart analysts understand that contrary to the efficient market hypothesis, it is blatantly obvious that, while there are long periods where the market may approximate fair value, there are equally long periods where price does not reflect value—in both directions. The trouble is that it is nearly reasonable, but not quite.

Some argue that the investing paradigm appears to have changed from the old school analysts like Munger who made a killing in the previous era. The argument goes that as the market becomes unreasonable for longer stretches—or even as leftist critics of central bank zombie capitalism charge post-truth—that value investing is a sure fire way to never make it. They imply that while it may not be wise, it is more lucrative to follow the latest investing fad until the moment there are no new players and the music stops, and that sophisticated formulas can determine the precise moment this occurs.

Bertrand Russell: The Financier?

To me, this appears to be a monumental exercise in hubris, but I will bracket it by noting that I am mostly, if not wholly, ignorant when I enter this space. Humility is not the same as saying nothing can known, but only that we shouldn’t be blind to the facts that are revealed to us. The confidence myopia that consistently interferes with the honest interpretation of the facts suggests that the problem is primarily philosophical, not statistical. Bertrand Russell would have been a superb financier in another life:

When you are studying any matter, or considering any philosophy, ask only what are the facts, and the truth the facts bear out, never let yourself be diverted by what you wish to believe or think beneficent social effects if it were believed. But look only and solely— what are the facts?

As has been so consistently observed throughout financial history, remarkable rises in equities have led many to proclaim a “new era” of investing. Their exuberance is not merely narrow self-interest of the kind Upton Sinclair so famously quipped. Rather, the history of rises like Tesla (cool graphic linked) suggest that crowds at times valorize the financial market’s noble mission to bring the limitless abundance of the future into the present. Today, these crowds are telling us they can anticipate the exponential growth allowed for by technology like AI to fundamentally transform the nature of assets in the present.

Russell is my authority of choice because this is a discussion about how we know what we know. I recall from my high school philosophy coursework that the bears like British financier, Jeremy Grantham, and John Hussman’s positions are in a really strange place in Russell’s Venn diagram1 of knowledge as consisting of true, justified, belief. Their beliefs are justified, but not yet true. If their analysis holds, it may be shown that the state of the market today is a kind of Gettier problem, the epistemological challenge to the classification of knowledge as true, justified, belief. That thought experiment famously proposed that a true belief can be inferred from a justified false belief due to epistemological luck. The classic image of a mirage in the desert is instructive for financial markets:

Imagine that we are seeking water on a hot day. We suddenly see water, or so we think. In fact, we are not seeing water but a mirage, but when we reach the spot, we are lucky and find water right there under a rock. Can we say that we had genuine knowledge of water? The answer seems to be negative, for we were just lucky.

Are we in a mirage? I will fall back on Munger’s worldly wisdom to say that we cannot know for certain. But I would like to spend the rest of this post to lay out the shadows I see, which may or may not be proven true at some point in the near future.

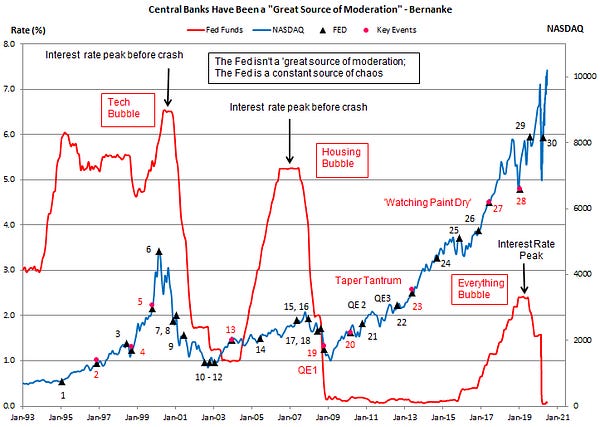

Look No Further than the Power of the Fed

The facts do not come from any special expertise, but just what I see as an everyday observer. There is a great PBS documentary that I highly recommend, titled, “The Power of the Fed”. In a critical sequence, Axios reporter, Dion Roubin lays out all the important details:

All these brokerage platforms saw the largest growth of new users they'd ever seen because people said, "Now is my opportunity. I'm going to invest my money in the stock market. I may not understand what the Fed's doing or how it works or what exactly is going on. but I understand the Fed takes action, stock prices go up, these people get rich." And it became a very clear mandate for people: "If I want to get in on this economic recovery we're having, I've got to buy stocks. [cuts to social media clip from a user flaunting cash from stimmy advising followers to put directly into stocks].

The author of the Felder Report, noted in a recent newsletter that app downloads for Robinhood declined sharply in the third quarter, and day traders are now increasingly likely to spend their time instead calling gambling hotlines. Moral hazard is to blame for these novice investors moving up the risk curve into equities and crypto, Roubin continues:

Jerome Powell has become a kind of cult figure, master of the money printer…It doesn’t really matter if something is a good buy or if it’s fundamentally sound. There's been so much money injected into the economy that people just need things to buy. [Interviewer: What you’re describing is mania.] Certainly we are in a mania because, again, the Fed has put a floor underneath asset prices. There's only one direction that things can go, and that's up. Otherwise, the Fed will step in and act. So if things can only go up, why wouldn't you just buy?

Precisely at the moment finance officially broke from the real economy in August 2020, I visited with an old high school friend, now a financial professional, over dinner one night. Referring to what I considered to be a decoupling, I asked him a very simple question, “Can asset prices ever go down?” His answer was revealing, though somewhat tongue-in-cheek, “No, General Powell would prevent that from happening.” Little did he know, General Powell would take the cue from his foot soldiers, likening his efforts to prop up the pandemic economy via wealth effects to storming the beaches of Normandy.

History tells us that war’s aftermath is always painful, and the pain is in proportion to the stubborn, unreasoning commitment without adjusting for changing circumstances on the ground. Peter R. Fisher, a former senior official at the New York Fed, first explains how inducing a 50% across-the-board bump indicates something has gone awry in market valuations. He then clarifies that this is no reason to celebrate because we ought to be thinking beyond the here and now:

The Fed, having pumped asset prices to historically high levels, doesn't make me feel comfortable. I'll be—I feel as anxious today as I've ever felt about the financial world because of my belief that the Fed has been pumping up asset prices in a way that is creating a bit of an illusion. I think the odds are now sort of one in three—very high—that we will look at this as an epic mistake and one of the great financial calamities of all time.

The bezzle has begun.

The Everything Bubble

They tapped Jeremy Grantham to give the kicker:

They have the housing market, the stock market and the bond market all overpriced at the same time, and they will not be able to prevent, sooner or later, the asset prices coming back down. So we are playing with fire because we have the three great asset classes moving into bubble territory simultaneously.

He made a similar point in an interview with The Financial Times, but with a few more details:

To use that as a yardstick and say ‘well, U.S. stocks aren’t any more overpriced than the most over-priced bond market by a lot is an odd way to determine value. Why not use bitcoin?…It is a ludicrous idea to use a highly overpriced asset bond market coinciding with extraordinarily priced stock market. That doesn’t make me feel better, that makes me feel worse. It means that a 60/40 portfolio is doomed to have a terrible 10-20 year return.

Both points of emphasis, the fallacy of bench-marking and the drag on long-term returns following the superbubble, are the focus of John Hussman’s excellent newsletter.

Enter the small, but vocal online community of Austrian paleo-cons, who have long been warning of an “everything bubble” of truly epic proportions. In a lesson the Chinese are currently learning, the longer action is delayed allowing the difference between actual and inflated wealth to build up, the more destabilizing the burst.

As I noted in a post reviewing Michael Pettis’ book co-authored with Matt Klein, the bezzle first showed up in macroeconomic statistics after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, moving the U.S. and global economy to lower growth path than the pre-crisis trend. But as is so often the case with historical narratives, establishing the true starting point can be a tricky exercise.2 The arc of the bezzle almost certainly begins with LTCM, as Peter Schmitt implies above. The technology consultant and Berkeley polymath, Jaron Lanier, tells people of my generation why it is so necessary to learn what that was, “as we will be paying for it the rest of our lives.”

I will acknowledge that my sympathies are not with these Austrians. Nonetheless, I frequently think about the “92ers” explanation of the myopia of Ivy League economists, who in their mission creep of Fed mandates to include asset appreciation, have contributed to an escalating legitimation crisis in ways that suggest epic hubris. As one Greek parable on the ring given to King Gyges foretells, the desire to be made invisible and unaccountable is more trouble than its worth. That ring, like the extraordinary backstopping of financial markets through central bank interventions, is a freedom machine that is impossible to refuse. But its very invisibility, or in central bank parlance “independence”, ultimately enslave the appetites of the subject. Perhaps there is no alternative but to revive the Hubris Laws and ostracism, the project initiated by Solon of Ancient Athens to strengthen the hands of ordinary citizens against the elite’s arbitrary humiliation. The methods certainly changed (no complex financial instruments that bezzled in 6th century B.C.E.), but what we are now seeing could certainly be described on the same terms of humilation.

Not Wrong, But Early?

Short of Elizabeth Warren doing her best Solon impression, what is the practical investing advice to be gleaned from all this? On an episode of the Investor’s Podcast, the host, Trey Lockerbie, lauds Grantham’s track record at GMO, predicting the market tops of Japan in late 80’s, the tech bubble, and the precise bottom in 2009 when he wrote his favorite all-time letter, “Reinvesting when Terrified”.3 Grantham throws cold water on Lockerbie’s kind praise, admitting he was sometimes very early:

Let me say that we typically identify a bubble zone, often, it went on quite a lot longer. But it always fell below the point where we had suggested it was entering bubble territory. So, once it broke through the peak, the 1929 peak of 21 times earnings, we started to be bearish in 1997, but only a little bearish. And then, as the peaks rose and rose from 21 times to eventually 35, we became more and more bearish until we were screaming bearish and still the market went up for another year.

Drawing from the lessons of the Great Depression, Grantham goes on to say that their assessment of financial markets is often imprecise because the market is governed by complexity dynamics that render it unknowable. Better to be approximately right, than precisely wrong, he implies:

You can very seldom identify the pin that pops it…What was going on was an economy that had been unbelievably strong was turning down, but because of the lags in the data, the city slickers [of the Eastern seaboard] didn’t know it, but the guys out in Chicago who had businesses and farms knew things had turned down, so they decided siting around the club at lunch that they better take a few profits…what might rattle the cage [today]? [unexpected COVID trouble? inflationary expectations?] The biggest cage rattler of all is everything you haven’t thought about which could go wrong.

Like the Chicago country clubbers, we are forced to settle for warning signs. He gives two signs at each end of the cycle—risky stocks going up a lot more than blue chip stocks and confidence termites burrowing from ludicrous ventures without any business plans to the broader market. Supporting the first classic bubble sign, GMO recently released an investor note showing that percentage of Russell 3000 growth stocks with negative earnings peaked in 2000 and 2008. He argues that the SPAC phenomenon, like the Robinhood meme stonks, is only beginning the decline from their peak. The guide from October 21 years ago, when technology similarly unleashed rabid overconfidence, suggest they will decline by 90% or more in the coming months.

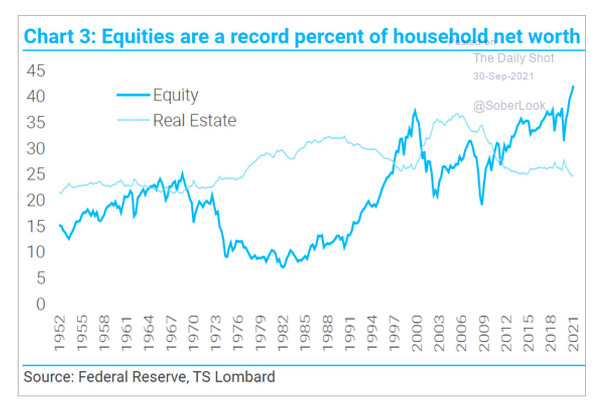

For both warning signs, we should return where I started—the result of Fed interventions pushing institutional and household investors alike in search of higher yields, leading to a generational clash between Grantham types and younger generation seduced by the prospect of finding the next GAFAM superstar firm. To be sure, this is a part of a longer trend interrupted by the housing boom, but the spike in equities as a share of household net worth after March 2020 is striking.

Recalling the point about decoupling, this run-up on equity prices is occurring at the moment some very sophisticated observers are detecting discernible declines in consumer confidence to the point that they are making the bold call of recession by the end of the year.

Speaking of flashbacks, remember the financial plumbing problems that were the subject of Crashed? They might return with a vengeance. John Dizard reveals an important little detail in the first link. Autumn is traditionally the season of financial panics.

Both COVID-19 and the GFC of 2008 were grey rhinos; we saw and heard them coming from a mile away as they were simply too big. Arguably, the most prescient analysis was Robert Brenner’s piece, articulated in the LRB as early as 2003. In 2005, the Economist also wrote a very good explainer on what could happen if subprime went bust. In a problem that is familiar to Grantham, the problem for Cassandras the world over was to gauge the precise timing of the financial crisis that they knew was approaching. When will debtonation day come? Smart money suggests can only defy the laws of macrofinancial gravity for at most 4 years, the observed time it takes for reality to come home to roost.

Source: John P. Hussman, Wealth is in the Denominator, October 2021

https://www.hussmanfunds.com/comment/mc211015/

It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future

Before leaving Beijing in June 2019, I remember talking about an article, titled “Why it’s so Hard to Predict the Future”,4 with a good friend and colleague from my Carter Center days at our local watering hole, the craft brew pub just outside the south gate of Peking University’s campus. I had not encountered Isaiah Berlin’s distinction between foxes and hedgehogs, but I remember being captivated by it. Foxes are generalists and hedgehogs are specialists. Rhetorically, the former constructs arguments with words like “however” and the latter with “moreover”. As C.P. Snow once remarked in the context of elite British university life, they constitute two distinct cultures that require each other’s insights for “society to think with wisdom”. I structured this post as a philosophical exploration because I remain influenced by this view of forecasting that I believe is more amenable to flexible revisions to account for the wildness that lies in the wait.

Some might argue that the inflexible hedgehogs in this post are not the Renaissance math whizzes or the Exponential Age investors, but those who share Grantham’s assessment. After all, when you make authoritative predictions that are wrong as GMO has done in successive forecasts, shouldn’t you adjust? Shouldn’t the investors cited here adjust for the new terrain of monetary fueled bailout capitalism?

What is currently unfolding in the Chinese property market, a sector many policymakers once believed could be similarly engineered, implies something rather different. Indeed, just three years ago, those who took the short sell position were roundly ridiculed. One investment strategist, Patrick Chovanec, offers a clarifying analogy to those who lack patience and are too eager to adjust away from what fundamentals suggest, “If you have cancer and the doctor gives you three months to live, and you live much longer than that, you still have cancer. You wouldn’t stop by your doctor and laugh at how wrong he was.” Value is metaphysical and Gettier problems take time to reveal themselves. From time to time, crowds fool themselves into thinking they possess forbidden knowledge that proved to be luck.

The 21st century philosophers like Russell may have been the first to articulate JTB conditions formally, but the idea is of course part of an older philosophical tradition dating back to the Socratic dialogues. Socrates articulates that “true opinion” is a necessary but not sufficient condition for knowledge in Plato’s Theaetetus.

On the point of Chinese imbalances, I got immediate push-back on Twitter that the fissure was even further back, around 2005. I knew this, as Pettis makes this point frequently. I responded with a political example on the other side of the Pacific. Interestingly, the overreach unraveling norm-based governance on each side of the Pacific, commonly attributed to the personalities of Xi and Trump, can probably be dated to well before either smelled power, around 2008, and the spark has little to do with the prior leadership. I will leave it to the political scientists to sort out.

At almost exactly the same moment, I advised my dad to purchase Ford at $1.55 per share. If he took the advice of his 13 year old son, he would have multiplied the value of his investment by a factor of 10.

The meat of that review article, the Simon-Ehrlich wager, connects powerfully to an annual letter Grantham wrote on paradigm shift of rising commodity prices. Though incredibly topical, I will save further elaboration of that letter for another post after I finish reading Range.