The Race between Singularity and Nightfall

A Review of The Exponential Age by Azeem Azhar

“We have created a Star Wars civilization, with Stone Age emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology. We thrash about. We are terribly confused by the mere fact of our existence, and a danger to ourselves and to the rest of life,” EO Wilson.

Recently, I’ve been encountering discourse on cryptocurrency that I believe has now reached a ludicrous apex. Just like in 1929 and 2000, the chorus that we have reached “a new era” of investing where returns are measured in multiples rather than percentage terms is growing so loud that it threatens to drown out all reflective thought on what has happened in the past or indeed what it means to be human. On Twitter, the journalist, Malcom Harris, advised one of these faces in the crowd to read a fable from any era or culture to get their bearings underneath them for what could happen next.

Referring to these animal spirits, I remarked that fundamentals have a way of rearing their ugly head because, “We have created a Star Wars civilization with Stone Age emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.” The American naturalist, E.O. Wilson, is overstating his case here. Futurists demonstrate that our technology has not yet reached its “godlike” potential.1 Those who observe the course of human affairs with the long view, such as Steven Pinker, know that collective norms that govern behavior have shifted radically since the Stone Age. Norms also undergird institutions such that the ancient inspiration of various institutional forms does not mean their applications are themselves ancient.

These caveats notwithstanding, this remark is perhaps the most eloquent rendering of what the author, Azeem Azhar, calls the exponential gap. The key idea of his book, The Exponential Age, is not so much that realizing the potential of exponential growth to general purpose technologies (GPT’s), not only achieving breakthroughs in computing, but using that initial breakthrough for still more breakthroughs in energy, biology, and manufacturing will send us on an escape velocity path to nirvana. Rather, there are all these places that are likely to frustrate before we get off the ground unless we take on the urgent work of forging a new social contract. In this respect, I believe the critics of this book are in a sense correct. Accelerating technologies are oddly not at center of Azhar’s analysis, choosing instead to focus on the political and social efforts to close the exponential gap through a renewed social contract.

All other efforts on each side of this settlement will serve to only deepen a kind of “post-truth” society. The chasm between discourse and reality is noted most vividly in an essay written by David Graeber where the Utopian promise of technology is betrayed by superimposing those fundamentally creative visions on architectures of Taylorist surveillance. On one side, there is a new strain of neoliberalism promoted by the Silicon Valley enthusiasts to encase the accelerating technologies. On the other, there is a natural, but misguided, response to fully insulate citizens from the dislocating effects of those technologies.

The disruptive technologies are a Pandora’s Box; they cannot be put back in the box and return to a simpler age. And as that ancient Greek myth foretells, that would prove undesirable because the technologies impart on the world improved means to handle the disruptions, which through the four familiar horsemen of the apocalypse threaten collapse if their protean power is not unleashed. The message appears to be: we simply have no other choices but to fight the exponentiality of the coming chaos with the creative capacity for humans to bring order to that chaos. COVID-19 was representative if only a dress rehearsal, “As the virus spread, it was both driven and combatted by the innovations described in this book. It proclaimed more loudly than any previous event, we are in an Exponential Age,” Azhar interprets.

The first part of this “review” will consist of a running commentary on all the observations the author considers to be potential sites where networked, accelerating technologies will fracture the contemporary social contract around the world. The second part will take a step back to briefly reflect on how remarkable the changes Azhar believes are likely to occur from a broader macrohistorical perspective.

A New Social Contract for the Future of Work

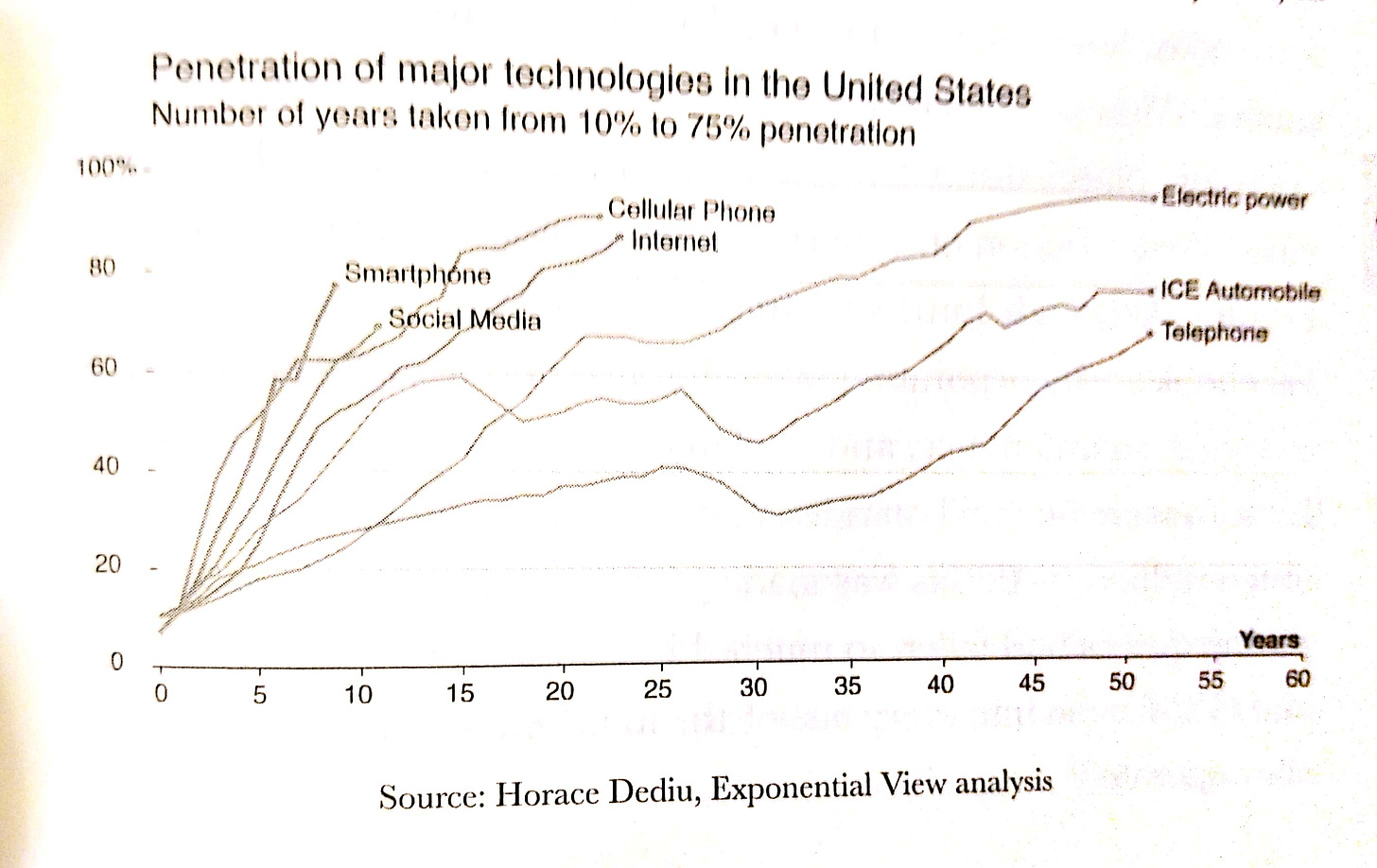

The most novel point about networked technologies relative to their industrial age counterparts is that they have the capacity to rapidly fracture the social contract seemingly everywhere at once, though not equally. Chris Hayes noted in a recent mailbag episode of WITHPod that American’s consumption of the Facebook newsfeed is actually the moderated version relative to places like Myanmar and Mexico where dead bodies are regularly shared and threats against individuals and groups frequently expressed. The reason is that the global market penetration of smartphones and companion networks offered by the social media sites is an order of magnitude greater than any previous technology. In fact, the global smartphone market is now so saturated that purchases of new devices are now declining from the market peak.

It is not the first time a technology rapidly spread throughout the economy without considering the consequences. The spread of the computer in offices across the country beginning in the 1980’s and how “it broke the human body”, a provocative claim in a recent Vice story on the historical context of zoom fatigue, should have been a harbinger for the smartphone era. But the key difference is the time intervals from adoption to saturation have collapsed.

The scale of the wealth produced in such a short time frame from this rapid spread of technology is difficult to overstate. Big data is the new big oil. Azhar writes that Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, and a few Chinese tech companies began to eclipse ExxonMobil, then the most valuable corporation in the world, in the 2010’s. This period was arguably a symbolic break from the old model of industrial Fordism wedded to fossil fuels.

In a pattern that pings back to other moments when novel technology was first introduced, the absence of fossil fuels as an input to its business model can create a vanguard for the new knowledge economy. The opportunities are vast, and should not be discounted. The old model of industrial capitalism continues to be nostalgically celebrated so often as to distort that the high security, high income jobs at the steel mill or the auto plant amounted to a Faustian bargain that sacrificed job satisfaction. As the heterodox economist and critic of post-war “Bastard Keynesianism”, Joan Robinson, once remarked, they reveled in the “privilege to be exploited”. The economic historian, Jonathan Levy, interpreting the sociological literature on 1980’s era mill closures in his book, Ages of American Capitalism, couldn’t help but note that workers often had more autonomy in the service jobs they found after the mills closed and were generally more satisfied. The challenge for the service sector dual economies that sprouted out of the Sunbelt cities like Houston, Levy implies, is to expand the critical sweet spot of autonomy and security so it is not merely the reserve of talented programmers.

The reality is often the opposite in the sectors of precarious employment, which have been the primary source of job growth since 2006. Azhar is not the only person who believes Foucault’s image of the panopticon resonates. Guy Standing, a British economist specializing in the growth of the “precariat”, the mass of low-wage workers forced to sell their labor and time in the “second enclosure”, notes that a judge quoted Foucault in a ruling against Uber, “a permanent state of visibility which assures the automatic functioning of power.” These rideshare and delivery drivers are also subject to a kind of arbitrary tyranny, where a single poor review for factors that are often beyond their control can cause the algorithm to deprioritize the user for task assignment. There is now a burgeoning genre of first hand accounts on how apps deprive many of their livelihoods that extends well beyond the author’s Deliveroo example. In other words, the Janus-faced nature of work in the two-tiered economy is on full display at these companies, with the mass of drivers afforded none of the perks of their corporate employees.

Perhaps this is only fair, detractors might argue. In capitalist economies, you are paid according to your ability to market your human capital in a way that differentiates it from the masses employed in the low-wage sector. Imitate us, and you too can enjoy these perks, so goes the usually left unstated meritocratic ideal tearing apart democracy. The fatal flaw in this logic, argues the Chicago-based labor activist and author of the book, The History of Democracy has Yet to be Written, Thomas Geoghegan, is that it becomes unworkable the minute a critical mass of workers take it seriously. Geoghegan spares no-one:

The whole postgraduate project—en masse college education defies logic or reason. The increase in the number of graduates that this program is likely to yield will be in business administration. And what do those extra college graduates with these business degrees do? They supervise the working class…It makes sense for the Knowledge Economy’s management caste to ensure that the workplace has even less agency for those whom the college graduates supervise.

The segmentation of the knowledge economy indicates a drift into the meritocracy trap. Workers who lack autonomy at work transmit restricted speech codes to their children who are taught that college is only way succeed in the modern economy. But unless they have the good fortune of having an exceptional mentor, their children likely lack the tools to succeed there because the economy is so afflicted with ratcheting managerialism.

He goes on to say that other countries like Denmark did not adopt this perverse credentialism and as a consequence their low-wage workers are paid more than double their American counterparts. Worker training such that it accounts for a substantial portion of GDP means that Scandinavian countries like Denmark have settled on a sweet spot of flexicurity conventionally thought to be impossible. According to that radically different version of the social contract suited for the exponential age, workers are provided with security so their families are not thrown into destitution in the event of employment loss such as the scores of folks who visited drive-in foodbanks during the pandemic. Critically, firms are also provided with flexibility when workforce development is an organized, well-funded process that reflects their actual needs.

Just as the social welfare state had to be shored up to catch-up with early 20th century GPT`s, flexicurity is the opportunity amidst a moment of social upheaval that could stave off the Great Resignation. Not coincidently, in places that have these arrangements in place, dramatic losses in middle-income employment have not translated into soul-altering rises in inequality of the kind seen in the liberal market economies of Anglo-America.

As the author underscores in the first section of the book, the coincident events of the Reagan-Thatcher revolutions were political choices that paved the way for the increasing market concentrations of the superstar tech firms that further eroded the earning capacity of ordinary workers. While Azhar emphasizes that the decline in labor’s hare of national income is more extreme than the rest of the OECD world, he actually understates the magnitude of the decline, one that occurred almost entirely in the 21st century, not further back as a result of Reagan-Thatcherite union bashing. The evidence the free market economist, Thomas Philippon, presents in his book, The Great Reversal, is abundantly clear—the decline in labor share of national income that significantly departs from the 2/3 ratio of ECON 101 textbooks has only been observed in the U.S. and mostly since 2000. This data casts doubt on the argument favored by Big Tech that capital has become more important in the production process as result of globalization and technological advance. Workers will simply have to make do with a “pause” in real earnings while all productivity gains accrue to capital owners. After all, the European economy, by no means a driver of recent creative destruction, also isn’t an isolated backwater. The EU has embraced a healthy dose of technology and globalization.

Philippon’s argument that the politics of market concentration, where U.S. lobbying expenditures dwarf those of Europe on a scale of 50 to 1, is central and technology does not naturally tip the capital-labor distribution in favor of machine owners is perhaps more persuasive today. But they were also likely at play in the prior Gilded Age of industrial capitalism when there was a similar “Engel’s pause”. The superstar firms of the late 19th century were more than eager to hire well-connected political operatives to cement their market prerogatives in stone, as one journal article in the discipline demonstrates.

In face of these political obstacles from megafirms with unlimited resources, what the author calls “the unlimited corporation” in Ch. 4, the prospects of Scandinavian-style reform, to say nothing of the AI social contract, may seem rather dismal. Yet what is known about institutional change does suggest an opportunity. In contrast with the author’s characterization of change as linear, my understanding of the American political system is that it is governed by punctuated dynamics, albeit still more responsive than the notoriously rigid Catholic Church. Two political scientists, Baumgartner and Jones, borrow a pithy phrase that I find to be useful, suggesting that action from the American Congress occurs in discontinuous jumps at moments of social upheaval—nothing at all, then all at once. One of the reasons why the Overton window in Congress shifted so dramatically in 2020 with even many Republicans suddenly willing to stomach relief packages in the trillions reveals a fundamental point about exponentiality. It leaves no stone untouched.

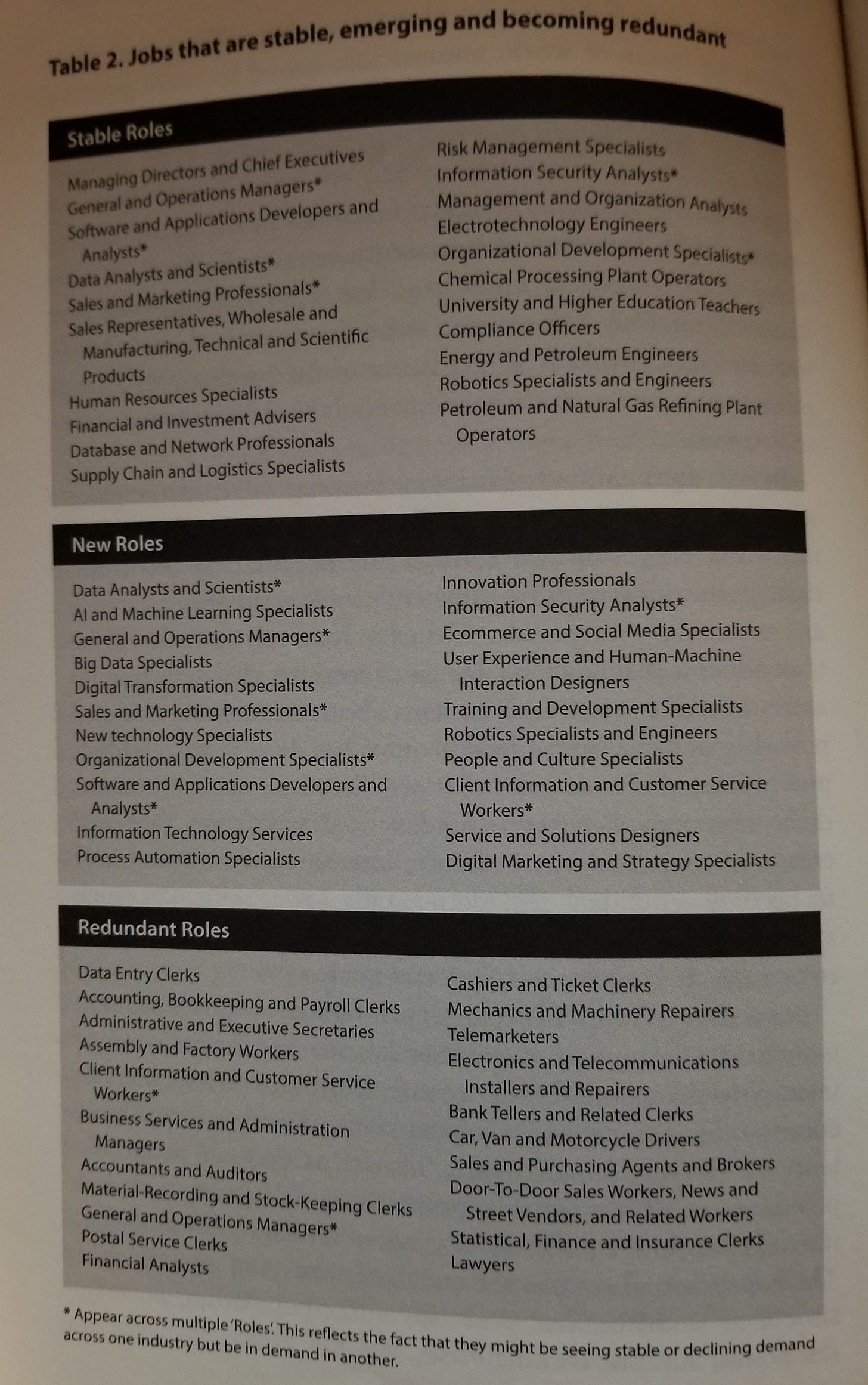

The author’s example of the Wall St. trader underscores what analyses of automation have known for a long time. There is an extraordinary mix of high and low-skilled jobs that are vulnerable to automation. If anything, many low-skilled “essential” jobs are more difficult to automate than jobs in “closet” fund management which nonetheless receive proper remuneration, exposing the myth of low-skilled employment. In an extraordinary example of Morachev’s paradox, a 2019 NYT expose on Amazon’s Staten Island facility revealed that the deadening labor related to the grasping of packages and affixing tape remain elusive to the brightest engineering minds at the company.

Lean into Energy Capture and Urbanization to Escape the Planetary Impasse

I remarked in the intro that COVID-19 was a dress rehearsal in that it is both driven and combatted by exponentiality. A dress rehearsal for what you might ask? IF history is even the slightest bit indicative, climate change. Climate change has an ominous presence in the collapse of every great civilization throughout history, writes the Stanford classicist and anthropologist, Ian Morris, in Why the West Rules (For Now):

Each collapse coincided with a period of climate change, which, I suggest, added a 5th horsemen of the apocolypse to the four man-made ones [of famine, state failure, migration, and disease]. Rising social development [his composite index for energy capture, urbanization, IT, and war-making capacity] produced worse disruptions and collapse but it also produced more resilience and greater powers for recovery.

Climate change is without a doubt the main event, and dovetailing with Azhar’s argument the climate emergency requires that we lean into the exponential growth of the 3 key indicators, energy capture, urbanization, and IT, to combat it. The fourth, war-making capacity has epoch defining implications for national security, state sovereignty and proliferation of non-state actors, Azhar writes in Ch. 7, the New World Disorder. It is a race between the exponential decay of natural capital and the exponential growth of productive and human capital. Whichever comes first will determine the outcome of the near future, condensing an energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables to at most 30 years.

We may not have a choice but to race, Ian Morris concludes:

The 21st century is going to be a race. In on lane is some sort of Singularity; in the other, Nightfall. One will win and one will lose. There will be no silver medal. Either we will soon (perhaps before 2050) begin a transformation even more profound than the industrial revolution, which may make most of our current problems irrelevant, or we will stagger into a collapse like no other. It is hard to see how any intermediate outcome… can work.”

The essence of that race is to build a stable planetary settlement to avert what the essayist Anusar Farooqui, known online as Policy Tensor, calls the hockey stick of doom.

Caption: Either Chart I happens by leaning into the capacity for energy capture, urbanization, and IT or human societies hit a “hard ceiling” of social development, arising from the exponential gap. That impasse would mean we will continue to tread along the curve in Chart II, Policy Tensor and Albert Pinto’s “hockey stick of doom”.

I have already written too much in this entry, so I will highlight just a few examples from Azhar’s book on what an exponential rise in social development might look like. Broadly, the possibilities for energy capture and “spiky” urbanization create new opportunities for re-localization, which the British economist, Ann Pettifor, inspired by an earlier essay by Keynes, titled National Self-Sufficiency, believes ought to be the foundation of the Green New Deal. Decentralized distributed energy systems can create slack for national utilities in so-called vehicle-to-grid systems, and may prove to eventually displace them entirely, Azhar writes. For the extra curious reader, I highly recommend the climate journalist, David Roberts’ three-part series of incredibly wonky explainer journalism on distributed energy.

On the urbanization front, Azhar notes experiments in urban farming carry similar potential for re-localization with the possible added benefit of breaking the political stranglehold of Big Ag. If this model pioneered out of necessity in crowded countries like the Netherlands is successful to the point that it can be scaled around the world, farming will likely be made less resource intensive, furthering even greater levels of urbanization in the future. That urbanization, in turn, is vital to realize the creative capacities for reasons well-understood to the agglomeration literature. The human capital economist, Enrico Moretti, notes in his book, The New Geography of Jobs, that scientists are found to be more productive as they gather in closer proximity, to the point that researchers can isolate an additional positive effect of sharing the same elevator. Creativity comes as a surprise to us, wrote the development economist Albert Hirschman, in a manner that benefits from these chance encounters in the elevator.

In terms of manufacturing, the spiky distribution of knowledge economy work from Silicon Valley to local schools improvising solutions to the shortfall of critical COVID supplies carries similarly transformative potential for onshoring. In the not-so-distant future, 3-D printers that execute plans for customized goods may leave us less reliant on the complex global supply chains developed during the 2nd period of globalization coinciding with China’s integration into the global economy. Though “dual circulation” of the kind that hearkens back to self-reliant blocs of the Cold War could constitute a threat, the more likely scenario, as Azhar’s example implies, is that distributed knowledge will complement distributed energy in our brave new world such that nodes in Shenzhen, or indeed the more peripheral Guiyang, will prove to be vital for knowledge production.

Geopolitics is just one place where the utopian promise of these visions can be betrayed in pattern familiar to the internet communities of the 1990’s centered around SF. They applied a counterculture flare to the internet’s potential to eliminate boundaries. The boundaries have a way of coming back, but in a new context mediated by the technologies, the early adopters soon discovered.

Decisions about how to police those boundaries will not disappear either for reasons outlined by the law professor, Lawrence Lessig, and summarized by the phrase, Program or be Programmed, “The only choice is whether we collectively will have a role in that choice….or whether collectively we will allow the coders to select our values for us.” If democratic publics do not instill transparency to algorithms imposed on us by the novel combination of the finance and tech sector, shrouded in opacity designed to preempt democratic action, the legal theorist, Frank Pasquale’s Black Box Society will have arrived. Even further along the road, but unmistakably a product of the Black Box’s profiteering is the Berkeley sociologist, Marion Fourcade’s dystopian formulation. Accelerating technologies plus Druckerian “what gets measured, gets improved” managerialism will produce the Ordinal Society.

This microeconomic neoliberalism will be the final death blow to the social bonds that formerly constituted the basis of American exceptionalism, represented well in the the mass membership organizations like the Rotary Club that flowered during the Progressive Era as improvised solutions to the Gilded Age morass. The ordinal society’s new divisions also expose the flaws of the old states & markets paradigm. To avert the reification of social boundaries in Fourcade’s warning, the solution is not to be found in state regulation which may prove to be a quixotic arms race against the sophistication of black box algorithms.

Rather, it is to take pointers out of the playbook of the Gilded Age social entrepreneurs who revived state-society relations. Following the shameless Gingrich-era assault on congressional state capacity, the current reality is quite the opposite, where economic, foreign, and social policy are completely outsourced from Congress to the Fed, the President, and the courts, respectively. The effect of unabated outsourcing will perhaps be to forever forestall a reversal of elite-mass disintermediation Policy Tensor believes is necessary to escape the planetary impasse.

Conclusion: Keynesian Optimistic Realism

I recognize that these are all dark visions and in the race between singularity and nightfall, our Stone Age emotions and medieval institutions might not be up for the task. Yet I share the assessment of Morris, Shafik, and Azhar that progress unleashes chaos in its wake, but also improved capacity to deal with that chaos. The question is therefore unsettled, and I choose to take the side of optimism, as Keynes so eloquently articulated, “For if we consistently act on the optimistic hypothesis, this hypothesis will tend to be realized, whilst by acting on the pessimistic hypothesis, we can keep ourselves forever in the pit of want.”

Michio Kuku writes in Physics of the Impossible, “Our own civilization qualifies a Type 0 civilization (I.e we use dead plants, oil and coal, to fuel our machines)…The most dangerous transition, for example, may be between a Type 0 and a Type 1 civilization. A Type 0 civilization is still wracked with the sectarianism, fundamentalism, and racism that typified its rise, and it is not clear whether or not these tribal and religious passions will overwhelm the transition.”