The End of an Era?

A Reflection on USCNPM China Town Hall with Speaker Jordan Schneider

So I spent most of today researching for a post on the much headier question of whether the market cycle is past its euphoria phase, the limits of knowledge, and what are the qualities that make a good forecaster. I quickly realized I needed to step away from the details I was collecting to write that piece well. Fortunately, I had scheduled to attend Atlanta’s local chapter for the China Town Hall events scheduled around the country via Zoom.1 My prior boss at The Carter Center’s China Program, Yawei Liu, convinced an analyst for the Rhodium Group and prolific author of China-related content for his newsletter and podcast, ChinaTalk, to give some remarks. The following entry is not a summary of that event as I do not plan to cover everything discussed2, but only the points that I flagged as significant and/or interesting as I was listening.

The Threat to People-to-People Exchange in the COVID-19 Era

The first thing emphasized in the conversation was the massive age difference between the national speaker, Fareed Zakaria, the moderators, Yawei Liu and Georgia Tech professor Lu Hanchao, and Schneider. Schneider’s relative youth makes him part of a growing contingent of young china watchers (YCW) who came of age academically and professionally at the perfect time. Specifically, Schneider acknowledged his growth at the prestigious Yenching Academy located on Peking University’s campus in Beijing. While many of the older China hands we’ve grown to know and love, including Bill Bishop and Nicolas Kristof, took advantage of the opportunities that existed in the 80’s, they were still relatively limited relative to my generation (pre-Covid, that is).3 Conversely, in spite of the famous midnight phone call between Deng and President Carter which ultimately increased Deng’s request to send 5,000 Chinese students to the U.S. twenty-fold, the opportunities for talented Chinese of Yawei Liu’s generation (born in 1960) to seek employment or education in the U.S. were an order of magnitude lower than they are today.

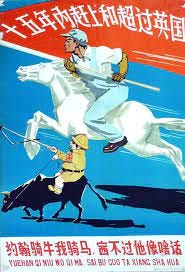

Increasingly, the fear is the momentous period of people-to-people relations on each side of the Pacific which shaped subsequent prosperity and mutual understanding may prove to be an aberration sandwiched between periods of isolation. In my darker moments, I wonder if an Economist article I read last year on the opportunity presented by COVID-19 to autocrats around the world is most presciently applied to China. I have little doubt that the future histories of this period interpreting the string of assertive actions from video game usage to the humbling of the consumer technology sector, wiping billions of market value, won’t fail to mention that Xi remained domiciled in the mainland throughout. A leader that had previously embraced foreign travel, Xi’s inward turn which played opportunistically into the threat of COVID-19 may mark the turning point of the Open-Up and Reform period that began in 1979.

In an equally prescient book, The End of an Era, the legal scholar, Carl Minzer, argues that the strain of self-reliant ethnonationalism has been surging in China since the late Hu era4 and later became articulated in the China Dream with the help of Xi’s lead intellectual advisor, Wang Huning. Until recently, however, these political narratives did not spread into broader cultural attitudes. That all appears to be changing, as the NYT journalist, Li Yuan, reported in her story on the increasing rejection of English as a Trojan Horse for decadent Western ideas. With the openness driving Deng’s decision to send those students to the U.S. now under question, she provides striking evidence for Minzer’s thesis that an authoritarian revival will spawn the counter-reform era.

In another eerie sign that Americans have detected the changing tide, many academic and language programs based on the mainland, including Harvard’s summer program, are relocating to Taiwan. In his remarks, Schneider emphasized that this should not be spun as an opportunity. We shouldn’t glorify the days of imposed exile of the 1960’s and 1970’s, when many eager Chinese language students desperately watched across the straight to catch any glimpse of the object of their mystical wonder. In a beautiful personal essay on what it was like to experience China from a distance, Orville Schell, director of the Asia Society, writes:

“We Americans, who felt so terminally shut out of this beckoning land, treated him as if he [Schell’s classmate who briefly visited Beijing in the 1960’s en route to Hong Kong] were a pilgrim who had kissed the sacred hem of the pontiff's robes in the Vatican. Because he had sojourned ― however briefly ― in this red celestial kingdom, we enthroned him as a minor god.”

Redistribution or AI Superpower? The Dilemma of China’s Governance

It is a tired phrase, but U.S.-China relations will be the most consequential bilateral relationship for the foreseeable future. To make the relationship work, it will not suffice to learn about China through the proxy of Taiwan, he emphasized.

The reason is rather obvious as only mainland China ties its legitimacy to the legacy of the Cold War and the mythology inherited from the Communist Party canon. The historian, Adam Tooze, made this point—so obvious, it is hardly ever explicitly stated— on The Realignment Podcast:

“As a historian of the left, [I reject] the centrist-liberal framing that starts from the totalitarianism theory under which it makes sense to as it were align Nazism and fascism with what you might call the National Socialist project of Xi Jinping’s China…But I think that is a profoundly misguided analysis….I don’t think the Cold War ever ended, the mistake was simply that we imagined that because we won the war in Europe, we had won the whole thing. We had never won the war in Asia…in any of the arenas in which we fought it… All that is happening is that we are waking up to the fact that we never had. And so this is not a regime, that is just an authoritarianism that is like a fascism, it’s a bonafide communist regime, warts and all, that’s what its heritage is.”

Unlike Taiwan prior to its democratic transition in the 1980’s, China emphatically does not have an “an authoritarianism that is like a fascism”, no matter how often liberal non-experts like Robert Kuttner5 confuse that history. The history is significant, Tooze argues, as it shapes how the Party chooses to deal with tech elites with independent spheres of authority. Channeling the political scientist Francis Fukuyama’s macrohistorical perspective, there is a distinction to be drawn between countries that have legacies of political development where elites have independent authority and are periodically disciplined by the state and more absolutist states like imperial China where elites were conscripted into state service. Conscription is a good perspective of how to interpret both the so-called tertiary distribution compelling voluntary donations and the project to forge AI superpower.

In some respects, where the Party leadership chooses to spend precious political capital conscripting elites in pursuit of these two aims is the dilemma of China’s governance, Schneider infers from President Xi’s recent essay in the cadre publication, Qiushi. In one door, China can choose the path advocated by the Stanford Professor Scott Rozelle, in his tireless (pre-COVID) campaign to convince stakeholders at provincial Education Ministries that his research reveals an “invisible crisis” of rural education and to invest in the left-behind youth, a casualty of China’s unprecedented urbanization. In a lecture I attended at Peking University in Fall 2018, Rozelle recounted the essence of his pitch. These “insurance” investments are never appealing, as it may be the case that these young people will never become the PhD’s their mothers dream of6, but the modest improvements in their basic skills and self-esteem will more than make up the difference in the returns to social stability. If he senses that he is losing the official’s attention, he reminds them they don’t want to go the way of Mexico.

In the other door, there contains the more appealing investments which will build the streamlined state capitalism of Xi’s dreams. According to Jude Blanchette on a recent Sinica podcast, titled the Red New Deal, Xi’s view is simply that consumer tech is decadent and entrepreneurship should be reoriented to harder technology sectors, such as AI and biotech. Dan Wang, the Gavekal Dragonomics consultant, is very to the point in last year’s annual letter doing the difficult work of digesting leadership’s thinking:

Xi declared this year that while digitization is important, “we must recognize the fundamental importance of the real economy… and never deindustrialize.” This expression preceded the passage of securities and antitrust regulations, thus also pummeling finance, which along with tech make up the most glamorous sectors today. The optimistic scenario is that these actions compress the wage and status premia of the internet and finance sectors, such that we’ll see fewer CVs that read: “BS Microelectronics, Peking; software engineer, Airbnb” or “PhD Applied Mathematics, Princeton; VP, Citibank.”

Wang’s point on finance is worthy of special emphasis. In between Biden National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan’s middle class foreign policy and newfound willingness of Chinese regulators to stand up to private equity, making Wall Street question its China gamble, there are few who are willing to fight for the interests of Goldman Sachs, Schneider repeated.

As Sullivan’s advocacy in Washington underscores, the dilemma of which policies most effectively sustain wealth and power is refracted in the policy discourse on the other side of the Pacific. Is it correcting the chronic neglect of ordinary people who will be made happy and content or investing in elite scientists and programmers who will accomplish great things? Listening to the libertarian economist Tyler Cowen on a podcast, I couldn’t help but see the Chinese obsession with wealth and power. He told the journalist Ezra Klein that while he is open to the possibility that pre-K spending gives substantial boosts to the innovations needed in the 21st century, he hasn’t found any robust econometric evidence. Demonstrating willingness to part with libertarian principles, Cowen argued that government should instead focus its efforts on less blunt policy levers to advance the primary aim of innovation. If you have even moderate democratic leanings, this argument lands incredibly strangely. Isn’t it an unambiguously good thing to reduce childhood poverty even if those children aren’t statistically likely to become brilliant inventors? Doesn’t equality of opportunity do more do advance the American idea than breathlessly listing off American collective and individual achievements?

Making Common Prosperity Work?

However, there is one crucial difference between the Chinese and American tentative moves toward middle class politics, which I tried to emphasize by asking a question at the event. In describing Xi’s efforts to revive egalitarianism which had badly drifted to labor suppression as his student Marxist critics contend, Schneider speculated President Xi might nonetheless lack “the political juice” to pull off Bernie Sanders-style redistribution. After all, Xi is not an omnipotent actor, a fact today’s reporting on the failing effort to expand experimental property taxes nationwide and contain the run-up on property prices reveals. There are all kinds of principle-agent problems that bedevil governance where the mountains are high and the capital is far away, as the Chinese proverb goes. But the most relevant for the ongoing Evergrande drama is that local governments in most cities almost exclusively rely on revenue from property sales, with only a few exceptions on the coast where the diversified high-tech service economy is located. Provincial elites will resist any measure from the center that has the potential to dampen property sales, and indeed the early returns on China’s experimental taxes indicate precisely that, and will result in the precious loss of revenue.

The relentless guarding of turf where government investment is still significantly elevated relative to the developed world may suggest there is something wrong about the Bernie Sanders analogy. Curiously, Schneider is likely not wrong that the central government reaches for this rhetoric when their efforts to rein in provincial elites fail. But they do so opportunistically, recognizing it is inappropriate for the Chinese economy, the macrofinance expert Michael Pettis argues in a recent essay and on a Bloomberg OddLots podcast. The challenge is not to fix the problem of poor aggregate demand in a consumer economy marred by household inequality but how to redistribute from local governments to households in an investment-oriented economy. With that background out of the way, my question posed to Schneider was simply this: “Is there a perennial political logic to economic reform in China?”

Pettis answers this question in the affirmative, “Local elites who benefit from the power and largesse of local governments are likely to strongly resist steps that would result in them having such a diminished role.” Schneider’s argument was in some respects more interesting as he shared an article written by his boss at Rhodium, Daniel H. Rosen, Xi: Failed Reformer? that I also cited in a recent thread reviewing Klein and Pettis’ book. The article is a wonderful piece of revisionism in that there is a growing body of evidence, both from coverage in the financial press and a wonderful book, The State Strikes Back, that Xi has been tightening his grip on the economy since 2015. Looking at the end result misses the broader picture, Rosen implies. Since Xi assumed office in 2012, he has proposed liberalizing reforms at multiple key junctures, but always in a one step forward, two steps backward pattern, Schneider summarized. Every time the Party dipped its toe in the waters of reform, they immediately saw all the downside from a party unity and short-term growth perspective and quickly retreated to the presumed safety of the status quo path.

These actions suggest that contrary to the lazy armchair theorists who bemoan that China has a 100 year plan, while Americans can’t even plan for their most immediate policy priorities against partisan gridlock, that the myopia may actually be worse on the Chinese side of the ledger.7 They have muddled their way into driving up a property bubble of truly epic proportions, if Pettis’ analysis on the difference between inflated and genuine values as representing a “bezzle” is to be believed. The hangover from that bezzle is at the very least, early 90’s Japanification, but without the advantages of having attained an already high standard of living. The tail risk is significantly worse, because it has been delayed for so long.

An Explicit Appeal for Strategic Competition

Hearkening back without returning to the Mao era of rugged self-reliance, the ghost town Schell once saw when he arrived at Peking Capital International Airport in 1975, China’s preoccupation with internal concerns will likely mean fewer opportunities for genuine bilateral cooperation. Paradoxically, the Mao-era benchmarking with other countries will become more common not less with the U.S. merely being the final frontier, Schneider speculated. Playing the optimistic contrarian, one potential upshot of this souring of relations between the U.S. and China is they might more directly confront the key global challenges of the 21st century through embracing this spirit of strategic competition, Schneider concluded.

When I was deciding which event to tune into, I was split between two of my prior affiliations, my alma mater, UCSD, and The Carter Center in Atlanta. I chose to listen to Jordan Schneider, mainly because I enjoyed reading a recent post, probing his Rhodium colleagues’ views on Evergrande. But I did not make the decision easily, as I am still very interested in what Prof. Michael Davidson said on how U.S.-China relations will make or break the current impasse with respect to stabilizing the climate system. Davidson also recently sat down with Kaiser Kuo, host of the Sinica podcast.

Especially the details of the Huawei/ZTE drama, which I confess I have never learned.

Including a few notable government officials and political figures who chose to take a different path. I vividly recall standing in a Peking University library staring at an old picture of the international students from the 1980’s. In that picture, I spotted a young Timothy Geithner.

Almost certainly related to the Great Financial Crisis of the 2008, as governance of the gargantuan American economy previous admired by Chinese liberals had been badly exposed.

Kuttner wrote in Can Democracy Survive Global Capitalism? (2018) , “China today represents a hybrid form of capitalism and communism that promotes Chinese nationalism, rewards billionaires, and suppresses wages, workers rights, and dissent. There is an old-fashioned word for that sort of regime: “fascism”.”

The statistics Rozelle provides on the percentages of mothers and grandmothers who imagine their underprivileged sons and daughters attaining the impossibly distant goal of a PhD in a similarly distant provincial capital— or even the most prestigious universities located in Beijing—are truly striking.

My only reason to hesitate (i.e. “may”) is there is plenty of myopia to go around, as I will write in my next post on U.S. financial markets.

I'm very very flattered you took the time to write this!