A Political Week, Heading into a Political Year

Reflection of the NEXTChina Conference Panels on COVID-19 Era and Revisiting the Red New Deal

Yesterday, SupChina organized the NEXTChina conference with two fantastic online panels on the COVID-19 era and the Red New Deal that I attended virtually. Both panels were engaging as they were connected with each other, and to two earlier Sinica podcasts. Both were all star panels. Here were the speakers for the first panel on China in the post-pandemic order:

And here were the speakers for the second panel on the Red New Deal, noting how like COVID-19 the pace of change in the “summer blizzard” of 2021 appears to be accelerating:

I will do my best to keep this commentary concise. But so much of what they said connected so vividly to what I’ve been seeing on Twitter the last few days I couldn’t resist but share the supporting evidence to their insights and explanations. As China watchers, we are all in the same boat, trying to digest in media res the dizzying flow of events coming out of the country.

Is this what it looks like when the gears shift?

This conference was incredibly timely because as the moderator for the first panel, Evan Feigenbaum, noted, “we are in a political week, headed into a political year.” That phrase of course refers to the fact that 6th plenum, a secretive gathering of around 400 men (yes, mostly men), have now concluded their meeting in Beijing this Thursday, and it is onto the 20th Party Congress next year. The Resolution on Historical Problems, the Party’s official articulation of its future, was passed on the final day, but the full text has not been released. For now, we will have to make do with the text analysis of the 6th plenum communique.

Why is this such a big deal? For starters, the Party does not do it often; only twice before for Mao in 1945 and Deng in 1981. In a concise explainer interview for NPR, one of the panelists, CSIS’s Jude Blanchette, does a great job of summing up, “Chapter 1 was Mao, Chapter 2 was Deng, and now it's on to the third chapter.” The topic of a recent paper by a wonderful professor at a university I attended, Noam Yuchtman and coauthors, further elaborates on the evolutionary form the Leninist muscle memory might take, coinciding with the classic three faces of power. Autocracy 1.0 is a regime that ensures compliance out of fear, Autocracy 2.0 manipulates information to induce compliance by persuasion, and finally Autocracy 3.0 where the state and its AI monitor and predict behavior to reduce the frictions of attempting compliance. In classic Foucauldian fashion, power has transformed, possibly even “progressed”, but it is no less pernicious.

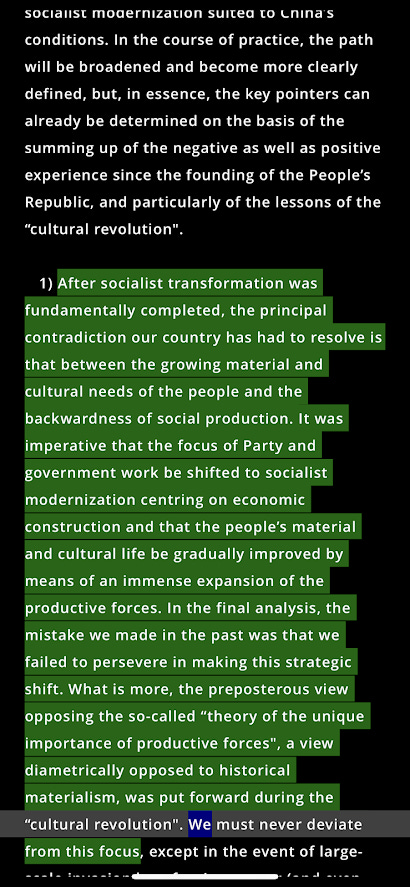

For those who need a refresher on Autocracy 2.0 to see where things might be headed in our AI future, ChinaTalk podcast host and Rhodium analyst, Jordan Schneider released an excellent (and entertaining) thread breaking it down. I bookmarked the principle contradiction tweet, what I regard as the key take-home point from that 1981 resolution:

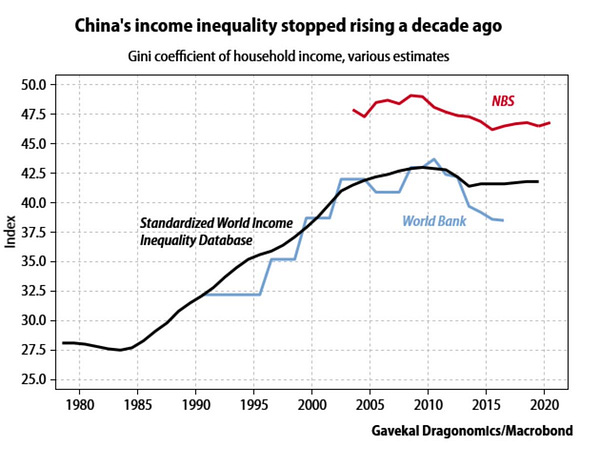

Elsewhere on CSIS’s website explaining the significance of the expanded New Policy Framework, Blanchette explains why Xi is not a simple return to Chapter 1 principle contradiction of class struggle that defined the Mao era, but a third evolution. To those looking for hints on what to expect from this week’s resolution, he notes the principle contradiction language was already changed at the 19th Party Congress in 2017. There, they triumphantly declared that China had already achieved the goal of becoming a moderately prosperous nation and that the Deng-era emphasis on capital accumulation is no longer the overriding objective. Or, if you prefer, in the language of one of Deng’s catchy phrases, “to get rich is no longer necessarily glorious.” Xi then articulated that the way to make China strong is by sharing the “cake” and eliminating “unbalanced” growth and “disorderly” accumulation of capital. In the four years since, Xi likely believes that he now possesses the confirming evidence on the untenable dangers of inequality and volatility. Indeed, he all but told us that he believes chronic neglect is the source of divisive populism tearing apart the West in recent Qiushi essays (links in Chinese).

Xi is neither a bleeding heart nor a rabid egalitarian, but a leader who deeply believes in the Leninist pitch, “east, south, west, and north the Party leads everything, and without a strong Party nothing is possible.” Aside for a few examples such as the promise of general purpose technologies to shore up Autocracy 3.0, President Xi looks around him and does not see a favorable environment for the ambition of upgrading Party control. Rather than Maoist upheaval, the natural inclination Xi has to both this external environment and a modernizing population increasingly desiring of status is to embrace a Bismarkian “everything must change” conservatism. A possible consequence of this radical conservatism arising from insecurity about the rest of the world is is a traditional revival that hearkens back to the era of self-reliance. The symptoms are perhaps most readily observed in culture but their consequences will likely be felt in the state’s orientation such that the overriding objectives are domestic.

The informed opinion of experienced China watchers like Blanchette and Andrew Batson in the tweet above is a natural segway to Adam Tooze’s views on the significance of COVID-19. There is a growing, if sometimes tepid, consensus that proactive management of the post-pandemic order requires closing the gaping discrepancy between discourse and reality. President Xi and many of his close advisors understand better than many in the West that it is vitally important to move from billions to trillions, the overall impression gleaned from reading Shutdown:

These are the kinds of demands easily dismissed as unrealistic. But after the shock of 2020, how much more evidence do we need? What needs adjusting is our common understanding of reality that we are actually in. It was those who have for decades warned of systemic megarisks that have been crushingly vindicated.

But in another sense, moving from billions to trillions is a necessary but not sufficient condition to escape the overlapping impasses. The Republican Party’s initial willingness to pass a $2.2 trillion economic stimulus does not make them any less of a criminal organization, as Chomsky has alleged.

Something similar could be said of China, and arguably for the same reason—anxiety that leaves honest self-examination of party history less than forthcoming. In a wonderful column released yesterday for The New Yorker, Evan Osnos clarifies the significance of the historical resolution as another gap, perhaps even an equally large chasm, between discourse and reality. Even on the purely economic front, top leadership understands and revealed in their COVID-19 macroeconomic management that a willingness to dispense with cash will not relieve the disproportions, because those disproportions are at least in part the consequence of that prior investment binge. That raises the question: could it be that China bears who have long been warning of megarisks will soon be crushingly vindicated?

All Eyes on Evergrande: Disproportions and the Post-Pandemic Recovery

The overall sentiment on the Chinese economy on both panels from Tooze and Lizzi Lee was laid out precisely on this discourse/reality framing. The strategies for redress lack the coherence of their diagnoses, according to Michael Pettis’ emphasis, “I think there’s generally more coherence right now in Beijing about the critique of China’s current growth model, rather than the coherence of what than coherence around what that alternative would really look like.” Pettis also explained on a recent episode of Bloomberg OddLots that he knows from his conversations with wonky Chinese regulators that there is generally more enthusiasm from the political class that a re-balancing can be achieved than those who actually understand the details.

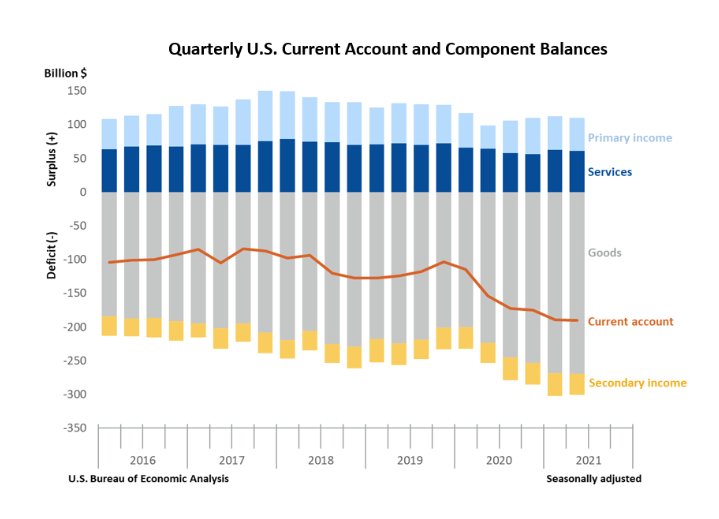

Tooze cited Pettis explicitly, noting how this political class places unjustified optimism in export growth as to be sufficiently large to offset the damage of real estate, seemingly unaware that the model’s strengths are linked to its limitations. The trade surplus with the U.S. and the world has in fact reached new records, but still paltry relative to the overall size of the Chinese economy. Pettis makes a similar point for the so-called tertiary distribution aka voluntary donations; when examining national accounts, the only candidate that is sizable enough for an effective re-balancing is from local governments to households.

The significant fact is that they do appear to desire these changes, even if reality does in fact have a vote, as Blanchette emphasized. From sticking to the three red lines, to the electricity crisis, to COVID-19 lockdowns, policy makers have demonstrated over the last 18 months or so that they are willing to stomach short-term losses for the potential of long-term gains. Looking at China from the mind of an economic naturalist, Lee suggested that there could be a very simple economic reason totally separate from the disruption to the Party calendar in January 2020—base effects. Economic performance was so crappy last year, even ok performance looks certifiably solid, she remarked.

The crisis also provided an opportunity to reform how economic performance is determined through GDP scorecarding, a globally peculiar practice of setting GDP as an input to the economic system, Lee noted. Through the change in principle contradiction language and reading the tea leaves for the historical resolution, Xi has channeled this opportunity into the New Development philosophy that intends to disaggregate growth so it aligns with the national interest. Lee conveys a Toozian openness that the shifting of gears achieved through a controlled demolition of the housing sector could just possibly work, reining in rampant debt and wasteful investments while reorienting the economy toward consumption.

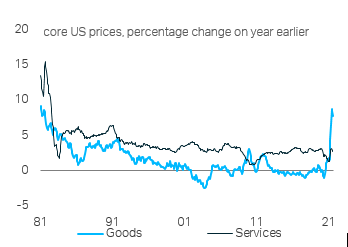

But in the meantime, and especially in economies where post-COVID remains more aspiration than reality, there is plenty of wildness that lies in the wait. Yasheng Huang gave a wonderful explanation of the inflation and supply chain pressure as a shift from services to consumer goods that hit on many of the same points of a thread I encountered a little over a month ago from TS Lombard analyst, Dario Perkins:

Predictably, subbing out “experiences” for “stuff” will create all kinds of pressures beyond supply chains on the global macroeconomy, because Americans are good at spending money but don’t produce stuff.

But does the surge in demand for goods mean we are headed for an inflationary period not seen since the 1970’s, as a recent note from Ray Dalio’s fund, Bridgewater & Associates, implied? Not according to Huang, who is firmly on Team Transitory, so long as vaccination continues apace and services get rolling again. The qualification there made me wonder. The disruptions may very well be here to stay, but they are likely to have different triggers in the years to come, coming from different nodes of the overlapping crises. Re-localization consistent with what technology allows is likely a sound strategy for the reason stated in last line of Tooze’s book, “We ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Can the World “Silo” Overlapping Crises?

The China skeptics who emphatically reject Toozian openness will say that their rise is one of hubris, caring little of the trust in partners required to govern a global superpower. Huang is one of these skeptics. Though he admires the state capacity of China’s Despotic Leviathan, even going as far as to say that it is unrivaled, he also argued that it is Janus-faced. For mitigation, the Chinese state machinery performed admirably well but also hid information initially and proved to lack legibility. That lack of legibility, in turn, contributes to the erosion of trust, where nobody, not even otherwise loyal citizens, believe the official numbers. If they can be made to distrust numbers, then grand narratives could also come under question. The Party averted that scenario because the mitigation proved more effective than many countries.

Yet the possibility highlights a real difference between China and democracies from Taiwan to New Zealand that had model responses. Because of the lack of intrinsic buy-in from society, independent eyes and ears on the ground, trust naturally erodes, a tendency not observed in other countries with greater capacities for self-correction. To be sure, the distinctive merit of self-correction has vanished in many other democracies. Huang emphasized American leadership deserves special opprobrium for its dismal performance. In the book on the stunning faltering of once self-correcting Anglo-American democracies1, Stein Ringen remarks that the situation is not all that different from over-bearing China, where rulers pretend to govern and citizens pretend to obey.

Increasingly, I’m openly wondering if the quality of signals within its administrative hierarchy are deteriorating. As I wrote in a post the other day on A&R’s Narrow Corridor, for the moment this is pure speculation. The Chinese state is fully capable of delivering the goods, and anecdotally, appears to have substantial buy-in from society, especially for the common prosperity agenda. That has been the case because Chinese leadership have understood the value of authoritarian resilience defined as a Hirschmanian “long voyage of discovery”. Deng’s famous dictum was “crossing the river by feeling the stones”. The idea is that central leadership can articulate a broad framework, attempt to implement at regional levels, who proceed to go through a series of iterations to refine over a period of time.

Alternatively, what we know about periods of modern Chinese history when the “shou” or tightening period continues without end, is that planning failures result. Dead letters abound of proliferating aspirations, but without effective instruments. Drawing from a Bloomberg opinion article, Lee notes how the latent conflicts are obvious in the effort to prick the housing bubble to ease the burden on urban working families and “avoid” involution. To the extent that their measures like the experimental roll-out of property taxes are successful, they will bring down housing prices, reduce household wealth, balloon the debt burdens of many households who attempted to climb the property ladder, and reduce consumption. Additionally, two-thirds of liabilities are owed to subcontractors, so can’t easily “silo” controlled demolition from broader contagion. Competing priorities are difficult to harmonize if central narratives are not merely dominant but overwhelming.

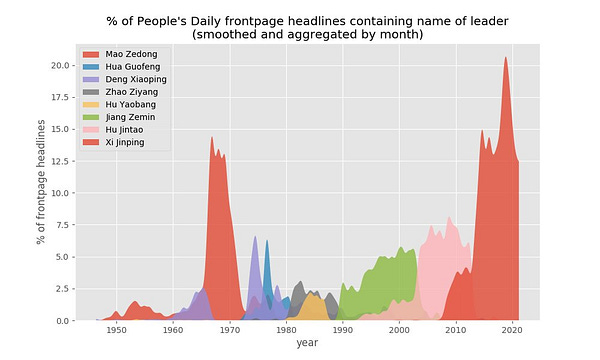

The caveats of Xi’s conservatism as incompatible with Mao’s mass line all still apply, but the overwhelming criteria is one place of real similarity as many casual observers of People’s Daily front pages have noted.

Nor is it the case that the relentless drumbeat of Xi and his vision for China is confined to national borders. Feigenbaum’s question on China not winning any popularity contests in OECD opinion polling was on point as it captures the exasperated mood on China from many in the West. In my social media circle, this article from The Atlantic really struck a chord, precisely because it describes how insufferable many Chinese actions on the international stage feel to observers and practitioners alike.

The confidence of having emerged from the pandemic triumphant has backfired, Huang argued. Internationally, China has lost the trust battle because its opacity and grandstanding has so thoroughly abused it. And even worse, at least for the moment, it cares little what the outside world thinks. Huang implies that this might be only temporary, speculating that when or if China experiences genuine economic difficulties, its leaders will come rolling back but without the credibility of their promises to bear.

The million dollar but open question Huang raised was: Is it possible to retain a siloing framework of cooperation on some issues of common interest to humanity like climate change while competing on other issues of secondary strategic importance? We can only hope that the virtual summit between Xi and Biden lays the basis to formalize this siloing framework soon. But the prospects are not great. Indeed, Tooze noted the Europeans tried to silo the investment issue, but that could not clear the substantial hurdle of China’s wolf warrior diplomacy.

There is much we cannot know, but at least one thing has revealed itself to be true over the last 18 months. The title of Carl Minzer’s book has been proven prescient. It is on to Chapter 3.

I don’t know if there is a British equivalent, but I do remember a quote that hanged on the wall when I worked at California Forward, a political reform organization, “the greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults“