Is this what it looks like when the gears shift?

Concern about the Artificial Intelligence Behemoths, Old, New, and Recombinants

“It is not the slumber of reason that engenders monsters, but vigilant and insomniac rationality,” Gilles Deleuze.

“By 1794…the one-sidedness of Kant’s Pure Reason is the only “freedom” of which the revolutionaries can conceive: ‘what was supposed to be a purely rational basis…turned the attempt into the most terrible and drastic event.’ Thus, formal freedom, for Hegel, is the historically limited origin of what the Revolution achieved as well as what it failed to achieve… On one hand, it is the point at which humanity “had advanced to the recognition of the principle that Thought ought to govern spiritual reality” ; on the other, Thought remained “without execution,” the basis of an “absolute freedom” with no ground in the concreteness of social life…. For Hegel, this attempt to realize “absolute freedom” is doomed to become its opposite. His argument …does not seem so far-fetched today,” Geoff Mann interpreting historical context of Hegel’s thought in In the Long Run We’re all Dead.

“The spirit of a people, its cultural level, its social structure, the deeds its policy may prepare…all this and more are written in fiscal history. He who knows how to listen to its message here discern the thunder of world history more clearly than anywhere else [for German readers who find additional resonance in the idiom: Wer ihre Botschaft zu hören versteht, der hört da deutlicher als irgendwo den Donner der Weltgeschichte],” Joseph Schumpeter.

Every once in a while, I find myself watching events from afar and feeling an irresistible itch to rewrite several commentaries at once. For the most interesting bits of information, the provocation to explore rarely results in a concerted attempt to coalesce the bits into something more than interesting. The aspect which makes the phenomena provoke, its very formlessness, is also that which inimical to disciplined study, devolving into observation (i.e. “market watching” “China watching” even “climate watching”).

The AI Hockey Stick

It’s not a coincidence that I am pushed into this thought whenever Kaiser Kuo and Adam Tooze team up to update us on the world situation. In that talk, Tooze gives a familiar type of answer, distancing himself from all aspects of systems thinking which have gained popular currency but not so far as to dissociate from the original finer complexity points:

“I’m not a systems thinker, but I’m a connected, joined up interrelated thinker…combined and uneven development for me is a touchstone—thinking as interrelated but inherently and systematically differentiated….constructed…having to be composed… coming out of the French schools, assemblage theory, skepticism of ontological solids, about the givenness of the macro world which we can start with, but [must from there] scope from the particulars to the macroscopic and back again.”

The explicit reference to French social theory is intriguing. I suspect he is describing, as one always does when asked to share their influences, only the tip of the proverbial iceberg. I hear him drawing from sources closer to home, chiefly German mysticism. The Whole exists in a dynamic relationship not only with other things but with itself, and that a subject activates and mobilizes the dynamic relationship through criticism, elevating the critic’s position in the historical process as an active co-creator.

Certainly true for anybody rubbing shoulders with executives and Chinese officials playing the part of the executives at the World Economic Forum. Less true for this humble blogger. Though it is certainly what animates me as well. The thinker I have in mind, Walter Benjamin, continues, the purpose of criticism is not simply the classical sense of education as directed judgment, training the arts of attention to take in abundance of signals, but “completion, consummation, and systemization.”

In the crooked timber of AI systems, engineering obfuscation for an idea as old as Benjamin, collective intelligence, the self-referentiality of all things nonetheless takes on a heightened effect via insomnia feedback. But make no mistake self-referentiality is principally human. These dynamic relationships are what we crave when we write small and large newsletters, transmitted via space-age technologies, collections of words and images arranged with intentionality. A fundamentally resonant orientation that controls nothing, but influences everything. “The best we have from history,” writes Goethe, “is the enthusiasm it stimulates.”

The following is not an argument because an argument presupposes intentional control which I have in part lost and in part relinquished as a kind of intellectual curiosity in the revealing. Arguments, many of us feel in the current moment, almost invariably fail, though often interestingly. As Anna Tsing might put it, another theorist skeptical of ontological solids, what will we put in the spaces in between the classically trained argument. In a similar manner to Tooze caveating his rhizomic inclinations, I must bracket out to say we can not let things float indefinitely without analysis, mystical methods to meander with complexity. I have neither the financial accounting knowledge nor programming skills to attempt anything more authoritative.

Yet the compulsion to complete—to systematize— drives me into revisiting my miniaturist commentary on the American economy, considering the other site of the Braudelian struggle, the monstrous corporate sovereigns whose wild oligarchs roam the capitalist jungle. They are riding a hockey stick every bit as dramatic as the one which exacerbates climate breakdown. A recent Bloomberg story on the spectacular global growth of data centers emphasized that in fact the two hockey sticks intersect at their midpoints. A profit machine systematically geared for optimization drives the world mad.

Corporations are Artificial Intelligences Too

Recall the question I posed at the onset, regurgitating Tooze’s metaphor for China rebalancing away from prior growth model which has been exhausted to higher quality growth: Is this what it looks like when the gears shift?

On other terms, when we stare at the assemblage we call capitalism, are we looking at something transformed? Is this capitalism still? Is the organism even alive, or is the terrifyingly wonderful analogy of the decerebrate cat apt, meeting essential needs so long as new stressors from the environment aren’t introduced?

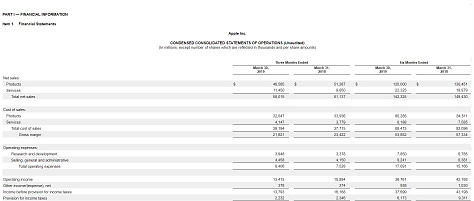

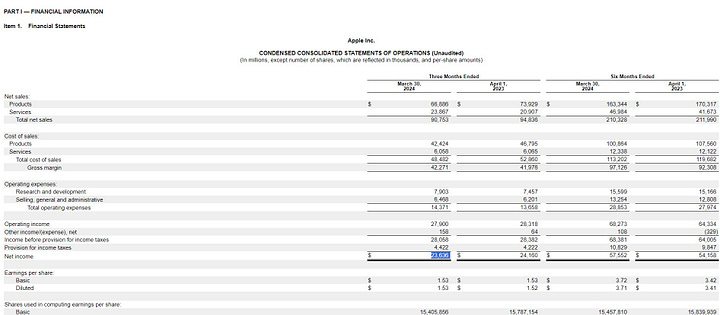

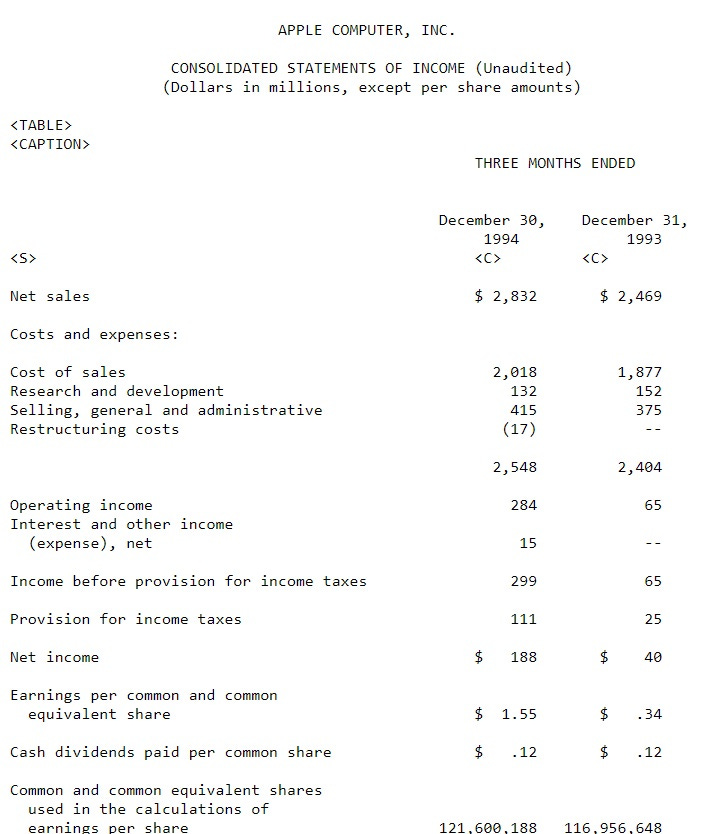

Attempting to answer this series of questions, I summoned various financial API tools at my disposal, and predictably I quickly developed the problem of too much data. How to extract meaningful signal? So it’s the impressions which registered first. From my untrained eye, investigating historical fundamentals questions are not what the tools were designed for. They appear to be present-oriented to an extraordinary degree. A presidential term is an eternity and 2008 is treated as Year 0. We will return to this point as I was unsatisfied with the ex nihilo projection as seen from above the API line, so I took the step of scraping past items directly through Edgar SEC filings, something that astonishingly I can do with a high degree of success (thanks GPT-4!).

Putting in pin in that, the question relates to what we might call the ersatz regime of accumulation, replacing the old Fordist model. I let the best securities analyst on Substack I know, Aswath Damodaran, provide the financial accounting identities, guiding me through which financial statement values to call:

The idea here is to listen for the thunder of world history, analyzing this bottom line item against the two options Damodaran lays out, buybacks and dividends. The first of Damodaran’s stories for how buybacks supplanted dividends as preferred mode for returning cash to shareholders is confirmed in the dataset—they are more flexible. During the crisis periods, buybacks dropped to zero, and remained at zero for the typical SP500 firm until 2011 following the GFC and until 2021 following the shock of March 2020. An interesting signal for the rigidity of obligations to shareholders is even as buybacks drop to zero, it’s almost always not enough to compensate for sharper decline in free cash flow to equity, and ratio rises relative to the pre-crisis point.

The other dimension, firm dispersion, is the same as Damodaran’s life cycle analysis. That there might be systematic differences in the proportion that actually returned relative to the potential dividend pictured above. The typical firm in the typical quarter returns about 83 percent in a top 50 company by market capitalization, and only 58 percent for the remaining firms on the SP500 index. Therefore, Damodaran’s life cycle point extends to established firms. Firms in the rest category are often firms which have not yet matured out of their growth phase when they had substantial reinvestment needs, and therefore are collecting out of inertia free cash flow which is not fully returned. The firms at the top of the universe, delivering steady profits, return cash and, with the exception of Jobs-led Apple, usually in rough balance between dividends and buybacks. In the set of most recent quarters, these firms are returning historically high proportions, often exceeding 100 percent at the median.

Damodaran’s overview presents how businesses came to make financial accounting decisions. You can glean two moves from the figures. The first move was to displace norms (in a brief aside he notes that in the Fordist days, dividends were taxed more than buybacks but inclination remained overwhelming slanted towards dividends) with instrumental rationality, led by publications like Journal of Applied Corporate Finance. Given that move, the supplanting of dividends was osmotic, and mostly occurred between 1990-2000. 2000 as the year Michael C. Jensen achieved his dream is largely true, and explains the acute disintermediation of elite-mass relations better than alternatives like import competition.

In rebutting what he regards as unvarnished nostalgia for the Fordist reinvestment model (the point is not to reinvest in bad businesses simply because free cash is laying around, he exclaims!), Damodaran misses the thunder. Much like negative oil and the reverse brought on by Russian invasion, the pandemic presented a surreal age of extremes with respect to cash flows. On the one hand, in March 2020 the sirens of a crisis blared red as return cash exceeded potential dividends by multiples that approached 5 to 1.

On the other hand, the crisis in the original sense of the word, decision fork, never materialized. Answering the question has capitalism been transformed affirmatively, the loudest, most charismatic voice wrote that August 12, 2020 was a watershed moment in the history of capitalism. I remember this unassuming date well, only because I happened to have dinner with a finance friend. For others without this marker it likely blended in pandemic time, so let Varoufakis explain:

“After 2008, everything changed…central banks coalesced in April 2009…That central banks’ balance sheets, not profits, power the economic system explains what happened on August 12, 2020. Upon hearing the grim news, financiers thought: “Great! The Bank of England, panicking, will print even more pounds and channel them to us. Time to buy shares!”

In 2021Q2, a dream world where everything was forever until it was no more, the typical top firm could not return cash fast enough, less than 40 percent for large megacaps and ordinary establishment outfits alike. Another Now and Bagehot-inspired books like The Price of Time and What’s Wrong about Capitalism have a common strand in they imply that 2020 could have been a moment where the proper meaning of crisis as krisis could have been capitalized. Instead, it went to waste, and completely unnoticed by old guard like Damodaran which clings to metaphors of efficient investment through fully rationalized financial accounting, muddled into an entity which has outgrown the boundaries they still believe.

The Techno-Feudal Concentration Crisis of the New Millennium

As a Greek, Varoufakis might be spiritually closer to the meaning of crisis. However, the Frenchman, Thomas Philippon, is closer to the historical truth in specificity of the near past without resorting to analogies which make us dumber about the past and present. The current crisis of American concentration and productivity is longer-running trend. He leads his 2021 Senate testimony with a chart that points the smoking gun, a marked decline in within-industry reshuffling which approximately tracks the 1990-2000 decade above for buybacks, though more sharply starting in mid-90’s. The connection is of course spurious, except insofar as there is a third cultural variable which I labeled instrumental rationality, the hurly burly of ubiquitous computing, that is acting on both. '

Philippon spells out the meaning of the above chart in his 2019 book The Great Reversal, how do we know which firms will be the superstars in 5 years time. Easy—the same firms that are superstars today.

The counterargument, bad concentration did not come until later, is embedded in a simple interpretation of SP500 turnover within the index over 5 year increments. For large companies at least, we can see that the shock of tech bubble recession is altogether different than that of 2008. The 90’s decline, occurred before the shock and therefore could indicate good concentration, while 2008 is concentration brought on by the shock itself. The general pattern is clear in each instance, sharp decline in turnover punctuated by a shock, then partial rebound in turnover in the recovery phase but not enough to compensate for initial decline such that turnover settles on a lower floor after each shock.

Philippon and Ruchir Sharma, in the only set of essential pages (p.242-246) of What’s Wrong about Capitalism, both attempt to disentangle the predicted effects of ICT with these other macro headwinds. Beginning in 2005, we see a sharp decline in labor productivity at the precise moment when computer technology became ubiquitous, drilling down to all walks of life. Sharma dismisses the idea that the new technology is to cause for the productivity decline. Compare the experience of writing this book before digital library catalogs, actually rummaging through library stacks, with the frictionless speed of accessing information today, he writes. In a handshake meme with Varoufakis, he points to the distortions of central bank capitalism, interfering with the normal turnover particularly as it pertains the vitality of small and medium enterprises (SME’s).

Revealing his first principles, he gives a glowing endorsement of the Taiwanese economy. Yes, they have one very large firm which must be large because of the incredibly specialized chip knowledge, TSMC, but infrastructural support to SME’s is not studied enough by those in the West. A healthy economy is organized in such a way that talented people only take a small salary/status hit when they opt out of the Organization Man path. This trend is a global story and highlighted in a 2019 paper reviewing potential impacts of the transition from early 2010’s Big Data to early 2020’s LLM/AI, and presumably, at some point in the future, simply AI, intelligence as judgment not mere statistical inference.1 Note that around the moment the key information technologies were introduced frontier firms become extraordinarily more productive, but equally salient is labor productivity in the long tail of firms declined relative to 2001 levels. The effect of GFC is observed in both, but only the long tail observes a hysteresis effect. As every economist working in 2008-2012 was painfully aware, the long tail employs most people.

Equally interesting is the global cleavage between manufacturing and services:

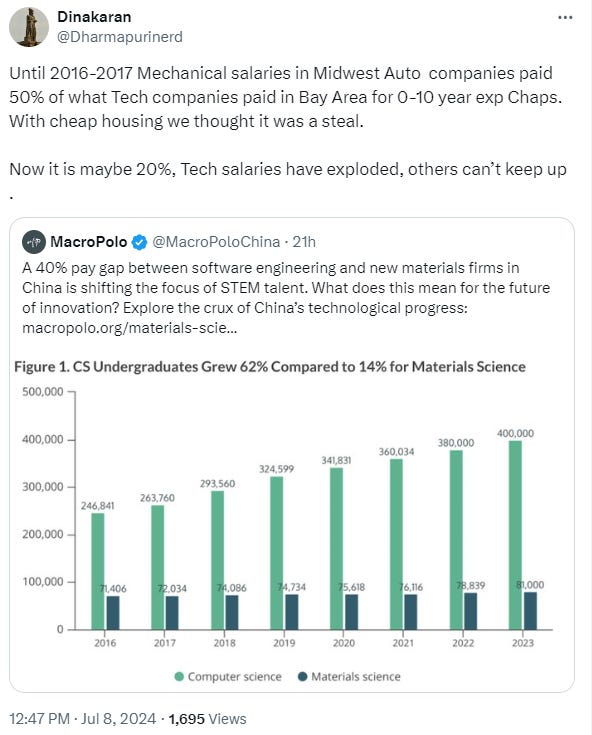

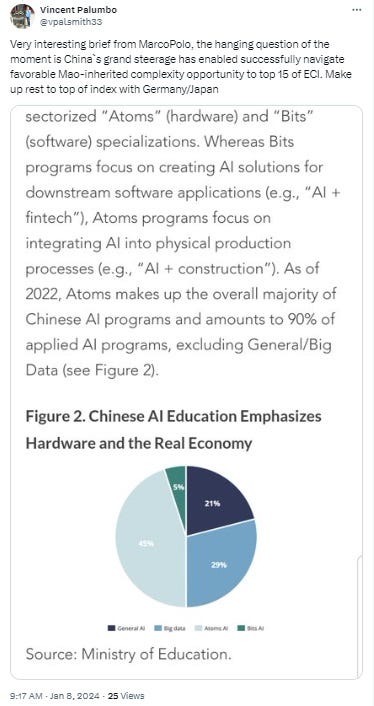

MarcoPolo has been at the forefront of reporting China’s approach to this problem to integrate AI and manufacturing as the way of the future. It’s genuine grand steerage the Chinese state can bear, where that the Biden industrial program of chips production in Arizona is psychological projection of the actual thing. Our liberal market economies, and perhaps more precisely family structures, have talent drift anarchically to those activities which offer the greatest labor market benefit, which do not necessarily align with that which offers the greatest strategic good. Innovation policy and industrial policy often grow opposed, Breznitz writes in Innovating in Real Places. Or more precisely, when the aims of innovation policy are promoted to the extreme they become their opposite, fully rationalized analytics on how and when people click but little relation to what most mean by innovation, promethean creation.

In the contest between Sharma and Philippon, they both argue no it is not the computer per se which is driving ailing productivity rates. But they diverge on what is the intervening variable. In Sharma’s case, government intervention in the economy is distorting Schumpeterian creative destruction, creating a bifurcated economy where the GAFAM’s are extraordinarily productive (with NVIDIA as a new entrant) riding the hockey stick of financial valuations upward but the cost of ailing productivity everywhere else as little firms struggle to keep up with the layering of rules. Philippon’s theory of the case is not entirely orthogonal as government intervention has certainly contributed to concentration. But the channel is direct— you need look no further than concentration. In his view, it is less of a story of the bezzle brought on by financial debt burdens and more regulatory barrier to entry story.

The third case that ICT itself is the distortion, and in a fundamentally in the manner frictionlessness misdirects human energies should not be dismissed glibly. Both Philippon and Sharma, as right-leaning economics brains, are usefully preoccupied by within-industry competitive vitality and information coordination yet also subject to the blinders of Hayek’s ecclesiastical view. Let’s consider the higher level of the dragonfly eyes, the systemic view, as more appropriate in the new environment where capitalism has been transformed. “For Hegel, the point is no longer to interpret the world, but to interpret the transformation of the world…'the bourgeois revolution…not to express the entire process of the revolution, only its concluding phase’,” Guy Dubord writes in a key critical theory text, The Society of Spectacle.

As recently as 2011, ExxonMobil was the world’s most valuable company. We live in a different world entirely. Exponential time is the key vector, Davies bring home in the Unaccountability Machine:

“Your biggest advantage in trying to understand an artificial intelligence system, at the start of this decade is that it is unlikely to be anything of the sort…But this isn’t going to be true forever….even the assumption you know what the inputs are isn’t going to be rock solid. At some point in the strange tense that might be called “Silicon Valley near future”, the way one has to talk about things that…are done in a small set of applications right now and will be ubiquitous within a decade, there will be lots of computerized decision-making systems which cross the black box threshold of comprehensibility, where, as [leading cybernetician Ross Ashby said] can only be treated… as a whole.”

The Arrow of Time through SEC Edgar Filings

Though it is certainly related to boring data collection and peer review reasons, I find it as interesting that Philippon charts ends right before the drama of the exponential curve begins. Another person who misses the thunder of world history!

Out of morbid curiosity, I mentioned I wrote some scripts to make market cap data go back nearly as far as Philippon’s dataset for SP500 companies. I could have considered it a waste of time, especially since I know that it is a matter of typing a few commands if you have institutional access to Compustat. But as the famous French mathematician Grothendieck used to say, time spent retracing knowledge that has already been created is not wasted. One of the accidental benefits is that with my mediocre programming skills, I generated loads of bad data, which allowed me to see what the output concentration data would look like under valuations that we currently consider absurd but could result if escalating plunder does not reverse. If careless calculations add three digits to an ordinary company that distributes lunchmeats (Hormel), the top 5 of the index would shoot to around 45% of the overall index. Imagining an 8 trillion dollar company in the next 5 years is not to entertain a pure hypothetical. History suggests financial crisis is a more likely end to the hype cycle, but the forest we’re in is so crooked I’m not so sure deep history is predicative. I think the wise course would be to prepare for a world where such an entity exists, perhaps arising simply from existing market share for AI services cannibalized to one or two firms rather than the growth currently forecasted.

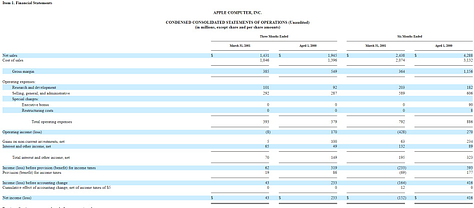

On the other hand, the cloud capitalists of 2024Q1 commanding $13 trillion eerily feels like their counterparts commanding $3 trillion 23 years earlier. Only Microsoft remains in the top 5. On that historical note, the process of scraping the reports is interesting for another reason. You can see the arrow of time. The first steps are visible leaps—take Apple’s text reports to HTML reports in 2001. The leap is the most significant lurch because it enables automated analytics to occur. The proceeding incremental steps of rationalization are hidden in the code, where only in the last few years of statements every number that you can conceivably request has a GAAP tag attached.

The philosopher Harmut Rosa likes to describe modernity in this way. Suppose there exists a panopticon. It would first examine all the ways we are visibly moving faster with mass transportation technology, to the point even when we do not rely on it, we walk around so fast almost to suggest from this detached POV that we are uncomfortable in our bodies. Compare me practically sprinting around a Beijing park across from an elderly bearded man, born and acculturated to the first kind of time, walking his caged bird. Bertrand Russell made a similar comparison when he attended PKU 100 years earlier, not at all certain his restlessness was right (end of Ch. 6).

Rosa goes on, my imagined panopticon, however, is more sophisticated than this, almost god-like in the ability to see all the invisible rationalizations to relentlessly push forward buried in marginal but additive adjustments to the surface foundations. First make it more table-like for predictable placement of scraped values, then add cumbersome ID’s, then add full GAAP taxonomies. Eventually, the dream goes that the systemization is so mechanized that what required an army of analysts to comb over the text reports prior to the internet only requires to rent out a switchbox or two within a data center. Rosa’s panopticon begins to analyze itself.

Visually inspecting these financial reports, it would be easy to stop here and join Philippon. That transformation of American capitalism occurred between 1994-2001. There likely exists some general law that any young student naturally gravitates to their formative years as transformation. Philippon arrived at Logan International Airport in the 90’s, and I write on this blog today. In any case, data analysis is protean, so I make the arbitrary decision to tilt the direction to across industry measures, simply because it is the main axis of the story I want to tell.

From this vantage point, the reshuffling rate certainly declined over the arc between the mid 90’s and 2012, but it was modest. The momentous period was when that reshuffling rate bottomed out around 2013, and systematically reorganized. In the prior period, there was significant turnover. Philippon notes that the company count of those firms which remained in the top 100 in the decade ending in 2000 was only 45, meaning there was significant churn inside and outside the top club. That churn had all but ended by 2010, exceeding 70, my analysis confirms. The reshuffling rate, formally the rank correlation between t and t+5, is contained to entirely within the club, as tech and gargantuan retail chains which know how to package their quantas of consumer data in the Costco, Walmart, Visa mold claimed their spots at the top. The FT reports the pattern holds for financial firms dominated by two megabanks, BoA and JP Morgan. And as the decline foreshadows, but too soon to tell for certain, reshuffling of this kind may be a one-off. The concluding phase of bourgeois restoration may have arrived.

It is difficult to envision a change into something else. Only in this sense does techno-feudalism make sense as an analogy. From the point of view of the participants, deprived of an imagination to see beyond what is presented to them, it can be difficult to imagine other ways of living. And yet the something else, given time to incubate, did eventually emerge to remake the decerebrate social order, a welcome reminder.

The 2010s and 2020s: “The Conscious Acceptance of Guilt of Necessary Murder”

This post, I fear, is a meandering mess in lieu of a method, which states the obvious. Technological rationality governs the world. Less obvious and hard to explain is that it is a rather peculiar kind of governing. It governs in a manner that flattens other perfectly valid, even potentially enlightening, ways of knowing. I have attempted a model to systematize the relations of what has transformed over time as a nod to good neoliberalism. Administrators, as prosaic as the spreadsheets they peddle might be, remade the world, Davies dedicates in The Unaccountability Machine.

And yet, I weave in these philosophy references and fixate too heavily on thunderous metaphors because I believe in my bones that the poetic ways of knowing are what enable a path through uncertainty. This perhaps relates to my deficiencies as rigorous thinker, and if my science was just a little sharper I would see clarity in the mountains of data. Instead, the mountains of data produce a feeling, summarily dismissed as soft by many, that frenetic pace is out of step with boundaries of the human senses. I’m reminded when I engage in these kinds of projects that the literal Chinese translation for computer is “electric brain”. I am seeking to understand something that my “head brain” cannot comprehend, and requires an appendage, a kubernētēs.

Electricity flows through internally as well as externally in the Enlightenment conception of feeling as enriching thought. On the one hand, the thinking sense usually informs that reversals almost by definition occur when they are least expected. On the other, the feeling sense sets the alarm that the present sensation is unmistakably boot-stamping. The reason why I opened with Mann’s essential book, thinking with Hegel and Keynes on the concept of honorable poverty, is I am persuaded by Healy & Fourcade conclusion, “Any institution that strives for this kind of [hierarchical, meritocratic] order-liness, with its ideology of clean measurement of differences and its monstrous technological affordances, has difficulty accommodating a community of equals.” How to solve the Hegelian puzzle— without execution in the concreteness of planetary-social life, formal freedom [exercised purely in market logic] becomes its opposite? Absent that formidable hurdle, projects alone, the Niebuhrian refrain goes, do not ease but accentuate the problem of injustice.

The sociologists, to say nothing of the philosopher-poets, will never rule. Perhaps we are fortunate to have the problems we do rather than the greater ones they would unleash. Simply put, liberal humanism, habits of governance which are not beholden to accounting abstractions, will not replace bad neoliberalism because it’s not up to managing a complex society at scale. What it believes is therefore not entirely true. Throwback neoliberalism2 of the kind Keynes championed, not coincidentally also hinging on concreteness, remains the best we have. The tyranny of a world without alternatives notwithstanding, the liberal faith must be preserved so that it can offer escape hatches in the turbulent present which if pursued often enough may become true.

Since this post was sketched as a companion to the View from the Cigar Shop, the American economy as it appears at eye level, from hubris to nemesis, I feel it would be appropriate to bookend this post at cloud level with how the companion started, Andre’s monologue on the nature of reality in the 1981 film:

“the 1960s represented the last burst of human being...And this is the beginning of the future now from now on all these robots now feeling nothing thinking nothing, and nobody left to remind you what life exists. [the physicist views slide into abyss as inevitable] others, however see pockets of light; these people can go on space journeys, refuel, and return to planet to reconstruct a new future. All attempts at recreating the monastery, islands of safety from civilized barbarism. What we need is a new language, one capable of expressing authenticity and representing reality in all its glorious technicolor, its awe, a language of the heart. When united with all things [just as the 60s gen sought out in last gasp] understand.”

Alfred North Whitehead, in a section immediately preceding a chapter titled The Romantic Reaction, writes that an event has a a future and therefore anticipation. Being the midst of things is key, he implies, precisely because it is neglected in the 18th century scheme3, which offered everything except for the essential elements of the psychological experience of mankind. I join Auden and others who periodically overdose on romanticism: will tomorrow come?

I’m an AGI skeptic because I believe two shifts are necessary, the first is to actual Artificial Intelligence, which anybody who has used the products knows does not currently exist, then to Artificial General Intelligence and two are distinct. It’s of course possible that once AI without the LLM crutch is achieved, a certain momentum to AGI is imminent. But it rests on a very big if, evidence that ordinary Artificial Intelligence as replicating judgment is possible.

Strange I know to date neoliberalism all the way back to 1926 and even stranger to attribute it to Keynes, given that neoliberalism is popularly interpreted as the movement which incubated in the margins at Mont Perlin Society as well as other strands during the Keynesian heyday and pounced during its decline phase in the 70’s and 80’s to remake the world. Following thinkers like Monica Prasad, neoliberalism is a project of active market construction, therefore The End of Laissez Faire. It has good and bad variants. This makes sense— what some right-neoliberals envision as the Agenda, what government doesn’t presently do at all but ought to do, is very bad and opposite of what Keynes envisioned. A good book has been long-listed recently on the right-neoliberals, When the Clock Broke.

As I opened by referencing Mann, the scheme persists.