Utopia, Still?

A Review, Wrapped in a Response, Inside a Grand Theory of Delong's Slouching Towards Utopia

“Is this capitalism still? This system’s death-agony has been heralded a thousand times. But now it may well have begun—almost as if by accident,” Cedric Durand in Fictitious Capital.

I have been meaning to respond to this question for a while now: Is neoliberalism finally over? Instead, I’ve been getting distracted by a question that is thematically and corporally related: is the project of instituting collective leadership in China finally over? Thematically because both have been trending in that direction but without the final nail in the coffin. Corporally because as we’ll see political reform in China and leveraging global growth to prop-up the zombified remnants of the neoliberal order are not independent questions.

At some point this year, I think it would be fruitful to sit down with someone who is asking themselves the same question and talk it out. I have a few people in mind when I get around to executing the idea of a podcast. One of the reasons why I would believe it would be fruitful is that, in a miraculous coincidence given the years of labor it took to bring them to publication, several books have been released —from Gary Gerstle’s The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order to Fritz Bartel’s The Triumph of Broken Promises— since the world irrevocably changed.

Less directly, Brad Delong also covers this question on the end to the long 20th century from 1870-2010 in a forthcoming book, Slouching Towards Utopia. He leaves the details, the tragic rather than comedic end to the American century, to future historians to sort out, aware that his interpretation would be unlikely to stand the test of time. But he too has the imprecise sense that things are shifting in ways that are not yet understood. Appropriately, his story, which he self-deprecatingly calls a “nonsense” narrative1, ends on a cliffhanger, “A new story, which needs a new grand narrative that we do not yet know, has begun.” I had a similar thought when Delong asked me what I thought of Gerstle’s book. I replied that I couldn’t help but wonder are we in the birth pangs of the mutualist era, the modern incarnation of the New Deal order?

The Story of the Neoliberal Order & Impasse in Four Ascending Lines

The tone of Delong’s book is reflective. Paradise was firmly in our grasp in the Eden of social democracy, but alas it was a Paradise Lost. For a while, this fact wasn’t too troubling as the neoliberal order seemed to muddle along, devising strategies to deal with the breakdown of Keynesian assumptions, but now it too has reached an impasse. The impasse does not reflect an incomplete commitment to market principles. Rather, the very devotion to those principles—tying to the mast—has perverse effects. On the perversity of improvised strategies, I think we first need to make a left turn to clarify what went wrong. Then, I’ll return to Delong’s interpretation of the wealth explosion of the long 20th century, unambiguously succeeding in growing the pie while also making inroads in slicing it, but utterly failing in tasting it.

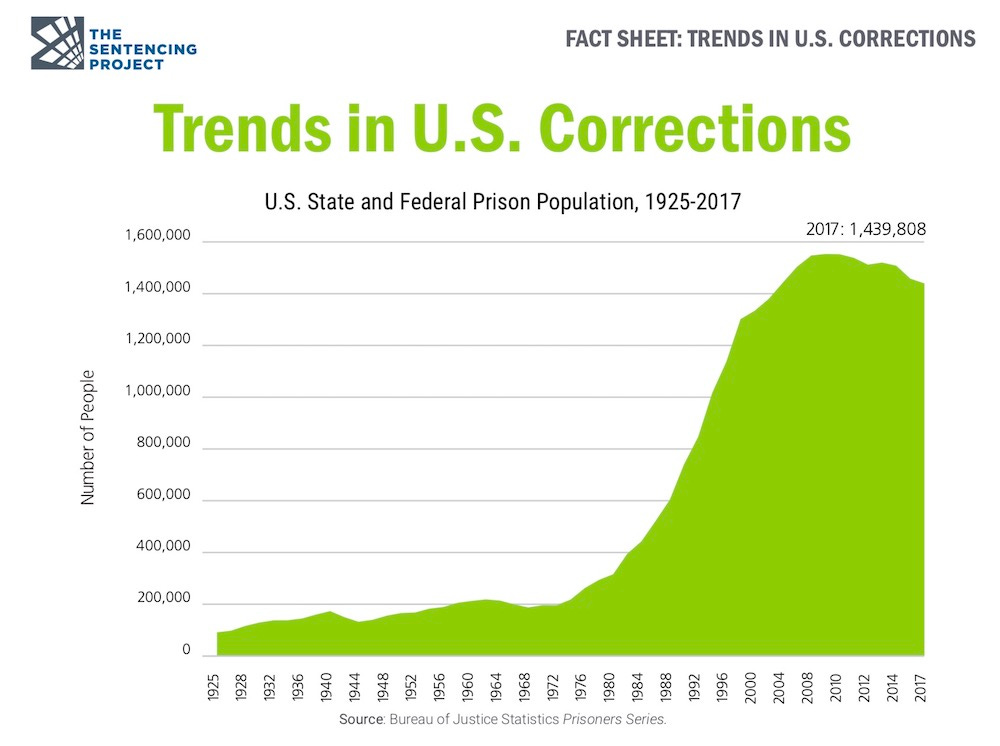

In a Red May discussion, Nikhil Pal Singh laid out the four mutually constitutive strategies to manage the transition away from the old Fordist model. Together, the economic sociologist, Fred Block, calls them the Ersatz regime of accumulation. Each strategy can be portrayed as an ascending line which can no longer ascend after it has reached a structural limit. They are as follows: the rise of the carceral state to manage the surplus population with factory jobs harder to come by, the birth of the asset economy to compensate for decline of middle class living standards, the development of the knowledge economy to fill the vacuum left by postindustrial society, and leveraging China as the fulcrum of hyperglobalization.

In short, the U.S. didn’t fail at any of its core objectives during the neoliberal order, but those objectives had an escalating logic—Brenner calls it escalating plunder—which simply cannot go on forever. To pretend otherwise is to be a Hayekian idiot, ignoring the power of his necessary foil, the Polanyian clamoring for social rights, Delong writes. I’m so drawn to Singh’s framing and how it dovetails with Robert Kuttner’s idea of political success, economic failure, a historically reliable pattern of successful failure, that I think it is necessary to extend it out further with a few charts:

The neoliberal order (1) forged a bipartisan consensus around mass incarceration, covered in the Netflix documentary 13th, which allowed cities like New York, which were as recently as the 1980’s viewed as ungovernable, to see escalating property values as intended. This was the dark side to the neoliberal “order”, an authoritarian liberalism often referred to as the New Jim Crow.

It also (2) reconstituted middle class life through asset manipulation in ways that were so extraordinarily successful financial professionals now speak of “a new paradigm” of wealth/GDP ratios. I argued in 12 tweets that this paradigm is pernicious. As the experiences of late 80’s Bubble Japan and involuted contemporary urban China attest, it causes young people in particular to toil endlessly to service mortgage payments. For that reason, someone, possibly the technocrats at the Fed but more likely whoever claims the example of Frances Perkins2, must somehow engineer a thorough reversal of wage rigidity/asset inflation logics.

As we’ve seen so far in 2022 with Biden’s initial approval from independents evaporating to inflation, running the economy hot for a time won’t do, except possibly in a delayed way if stag-quality3 gradually burrows into risk assets and eases affordability. Of course, in the long-run we’re all dead—waiting for that scenario might lead to another Trump term in 2024 in the meantime, to say nothing of the upcoming November midterms.

(3) Alongside Sweden and Finland, the Anglo-American world has seen a complete transformation in favor of intangibles and the Knowledge Economy. This year, two authors, Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake, have revisited a question they dismissed to the anemic recovery of the Great Recession in their prior book, Capitalism without Capital, on why intangible investment shares have stalled after enormous growth amidst the temporary productivity surge.

Their analysis dovetails with Singh’s narrative of ascending line approaching a terminal limit, followed by stubborn belief that can transgress the limit as fantasy. I think I disagree on that fantasy point; if policy were to converge around Unger’s vision of inclusive vanguardism could perhaps escape the impasse. Restarting the Future lays the path towards inclusive vanguardism, emphasizing that barriers to growth in this area are not as solid as barriers elsewhere.

(4) Which brings me to hyperglobalization. Delong’s characterization intrigues. He is perfectly honest admitting that he struggles to write an impartial history here. He acknowledges he is a product of the neoliberal era, arriving at Harvard in 1978, and finishing his undergraduate studies when the Volcker shock engineered plummeting energy prices, causing the crisis of really existing socialism in the Soviet Union to be exposed. He also reveals in the acknowledgements that in the process of writing the book, he was guided throughout by asking himself: What would my friend Larry Summers say?

As a card carrying neoliberal, he is abundantly clear; the task of reglobalization was essential. Channeling the philosophy of the original neoliberal, John Maynard Keynes, who pre-WWI waxed poetically about the virtues of globalization for residents of the British Commonwealth, Delong argues at some point along the way4 reglobalization became hyperglobalization. Critically reflecting on the Great Depression, Keynes opined, “above all, finance must be primarily national.” Delong’s message on reclaiming the Keynesian Age of Control, recognizing the limits of the ICT revolution celebrated in the 90’s as a boundless Utopia, can be interpreted as a similar moment of critical reflection.

Utopia is for Walking

The successful failure in each of these areas, a success that is an ersatz version of actual success, is related to Delong’s concluding question (paraphrasing): at what point is the global history that I characterize over the arc of the long 20th century from 1870-2010 no longer a Utopia? He invites somebody to lead a Jacobin assault on his book. That is, somebody willing to articulate the idea that neoliberalism signifies spiritual violence against the idea of Utopia, not merely a regression against cumulative progress. To paraphrase the Uruguayan historian Eduardo Galeano, Utopian realists are under no illusion that the only steps made are forward, but what is happening now is something more serious. We have stopped walking altogether.

During the thirty glorious years of social democracy, covered in Ch.14, the Global North was on that steady path. Biblically, they abandoned it during the neoliberal turn for the far country of the carceral state, asset & knowledge economies, and hyperglobalization, each promising salvation but bringing only bewilderment. Delong drives this point home from the Sermon on the Mount regarding failed attempts to build a new foundation, one built on top of rock and would withstand sustainability tests, by reiterating throughout the book this religious chant from Hayek’s ardent followers, “the market giveth, the market taketh; blessed be the name of the market.”

Contrary to Hayek’s devotees, the biblical image of abandonment reveals that there is nothing self-correcting about this drift. Once societies have lost their way, the natural path is, until acted on by some outside force, towards ever-increasing bewilderment. Americans, in particular, have been foolish in resigning this drift to fate. Martin Luther King, Jr. reminded in his writings and speeches before his death in the epochal year of 1968 that we can always return home to the marvelous foundation articulated at the nation’s founding of political rights. Moreover, King knew his Polanyi; those rights amount to nothing more than a hollow shell if they are not accompanied by broadly shared wealth. Or maybe he read his Mill.

This is what Galeano’s furious walking is for. To make wealth, what used to the preserve of the few, serve the benefit of the many. While acknowledging certain concessions needed to be granted to forestall revolution in Marx’s heyday or neuter the Soviet threat, modern conservatives argue Bismarck and other architects of the European-style social welfare state have had their day. After all, they don’t want to risk benign Bismarck transforming into the more muscular vision promoted by the architect of the NHS in Britain, Aneurin Bevan. In the face of limitless expropriation, attempts to climb atop the hilltop of history and yell stop are appropriately valorized, conservatives argue.

Here, too, they are foolish. As Delong wrote in a blog post responding to Piketty’s unexpected global bestseller, “A return to the 1960’s will not turn us into [the 60’s of] Maoist China.”5 Yet the primal fear arising from certain economic royalists is not entirely misplaced. Piketty’s simplified narrative of what Whiggish progress looks like from a wealth perspective on the Ezra Klein Show this week is clarifying. During the Belle Epoque period of pre-WWI Europe, 90 percent owned nothing, while the top 10 percent owned essentially everything. The Great Compression, the cumulative effect of two world wars and 30 years of social democracy, was nothing short of transformational if still unfinished. The wealth share that went from owning nothing to owning something shifted from the top 10 percent to the top 50 percent.

Dry wealth statistics understate the impact of this historically novel equality. The upper levels of the working class simply became middle class, a world-altering transformation, Delong notes. His colleague at Berkeley, Robert Reich, spells out the personal meaning of that settlement in Saving Capitalism—families like his could live the good life on one modest working class income. A few were even fortunate enough to have their children climb the ladder of opportunity, sending them off to be Rhodes scholars at Oxford to hob nob with future presidents.

To be sure, the distribution of Polanyian rights was radically unequal—the bottom half who owned no property still had no rights. And the 40 percent who only recently gained property had rather meager claims to rights. In the biased pluralism the classical political scientists of the era began to formally analyze, if their social rights were observed and respected, it was largely by accident.

Given the success of that settlement, not only for families like Reich’s but in the inspiration it engendered to governments around the world seeking to emulate the American way to economic El Dorado, it’s tempting to simply extrapolate. Thin property rights would be expanded to the bottom half and the 40 percent that gained access to property would have those claims solidified, so their rights could be more reliably represented. Instead, the crisis of the 70’s came and conservatives yelled stop, arguing in the Trilateral Commission that the crisis was one of too much, not too little democracy. In short, elites confessed rights should have never been extended to the upper levels of the working class and “things shifted back”— first with Nixon’s hand, then Volcker’s arm. Workers in the Global North paid the price for the controlled disintegration of the world economy, Yanis Varoufakis wrote in And the Weak Suffer what They Must.6

Political capitalism may have been more orderly and predictable under the Logic of Discipline but came at an incredibly revanchist price, “The U.S. today is in the same situations as countries like France in 1900 or 1910…The U.S. becomes a new Old Europe of the world and has a form of inequality today [like] Europe during the Belle Epoque period, very entrenched economic and political system.” Affluence breeds influence. And just in case you attribute that statement from Piketty on U.S. politics in the Citizens United era as French leftist hyperbole, it should be noted that is also the view of another French economist, Thomas Philippon, whose deep belief in free markets, properly structured, is more sincere than most American economists. In The Great Reversal, he shares charts showing U.S. lobbying expenditures as 50 times greater than that of Europe. For a similar moment where it paid that much to have political operatives insulate emerging business models from risk, you’d have to go to Late Victorian Britain, the last successful failure.

1995: The Coming of the Second Gilded Age

In an older draft of Delong’s book, I found a table of contents with a tantalizing suggestion given my fascination with the decade after 1995—that the second Gilded Age began then. Evidence supports this to a degree. Note that the change in gradient for inflation-adjusted home prices attached in (2) came around 1995. Yet a Gilded Age is something more. As I understand the term, a Gilded Age occurs when political polarization, economic inequality, extreme nativism, and social dislocation are in such confluence they are difficult to parse. Simple theories of how economic inequality fundamentally generates a cesspool of polarization, insularity, and corruption, parroted above, might be seductive, but are never satisfying.

The sharpest observers I know who have taken up this question, such as Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett,7 admit there is an intervening variable to all these factors which is difficult to measure precisely but easier to feel as an observant citizen. It is what I meant when I wrote in February that digitalized, atomized ways of living are a tragedy for those who feel. It is what Delong means when he writes, “the focus shifted from providing information to capturing attention—and capturing attention in ways that play to human psychological weaknesses and biases.” It is what FDR meant when he formulated his four freedoms. Only one, freedom from want, was purely material.

Putnam told my Beijing lecture hall in 2018 that there is a split in his early academic work and mature work as a citizen, vita contemplativa and vita activa. Something similar could arguably be said of Delong in Slouching Towards Utopia. I imagine him summoning his memory to recall what each year felt like, rather than an economist methodically tracking the changes in statistical indices. 1995 is the approximate moment when many of us drifted apart and lost the ability to taste, he implies, “Material wealth does not make people happy in a world where politicians and others prosper mightily from finding new ways to make and keep people unhappy.” As I wrote in February, the “others” group is currently filled to the brim with hucksters, modern-day confidence men, trained in the insights of persuasive technology to invade attention with all the force of Sun Tzu. The question becomes precisely as Barbara Jordan prophetically warned at the nation’s bicentennial, “Who then, will speak for the common good?”

Drawing from Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Delong writes his chapter on the Great Depression that Perkins may have not have solved the economic problem of the depression, but she did ignite a flame to new to American political life, and would be extinguished during the neoliberal turn, of “modest European-style social democracy”.

See next reference, Restarting the Future, for how stag-quality compares to familiar stagflation. Haskel & Westlake might be inclined to revise Tolstoy, all well-adjusted economies are exactly alike; imbalanced ones always different. Deeper point is stag-quality and stagflation might be a distinction without difference for asset values, and those with a more sophisticated view of financial markets like PolicyTensor rate stagflation scenario as more likely than others.

Which he doesn’t explicitly date, but can likely be traced to after his departure from the Clinton administration. Other authors, like Gary Gerstle, note that, like Democratic Presidents to come, there was a split in the Clinton administration between hopeful progressive promise and the realpolitick of managing global financial/geopolitical hegemony, symbolized by the split in his White House between progressive lions like Stiglitz and financiers like Robert Rubin and Teflon man, Larry Summers. When Stiglitz and Reich departed, the floodgates were opened for financial deregulation. Jonathan Levy’s Age of Chaos, while ostensibly related to the “controlled disintegration of the world economy” (Volcker’s phrase at the University of Warwick characterizing the Volcker shock), a euphemism for effects it unleashed on the Third World, were not fully realized in the U.S. until New Deal era controls on banking were lifted as Clinton left office. So Reagan may have been responsible for neoliberal policy genesis, but it did not become “an order” until Clinton shored it up, Gerstle argues.

Though Delong notes you wouldn’t have to look too hard in the late 1960’s to find people who uncritically admired Mao’s communism, or plastered Che posters in their college dorm rooms. This is covered in an important book I have not read, Maoism: A Global History.

This footnote is for Delong: you seem to have a close relationship with the econ blogger Noah Smith. He has a hot take on this subject, arguing that the Volcker shock gave the progressive project— doomed to failure in the 70’s— in America (emphasis mine) a second life. I would like to see an elaborated post from Smith, showing what the alternative past he imagines without a controlled disintegration of global economy would have looked like. Or possibly an episode of Hexapodia.

Putnam and Romney-Garrett’s book, The Upswing, has another interesting point of comparison with Delong’s—their common emphasis on Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward 2000-1887. The opening to their conclusion, “In 1888, American Progressive Edward Bellamy wrote a best-selling novel entitled Looking Backward 2000-1887. In it, the protragonist Julian West falls asleep in 1887 and wakes up in the year 2000 to find the America he had known completely changed. The cutthroat competition of his own Gilded Age had been replaced by cooperation…were his protagonist to walk the streets of today’s America, he would, unfortunately, find himself quite at home—in a reality more similar to his native one than the utopia he envisioned… disparities, gridlock…fraying social fabric…widespread atomization [all coupled with prosperity].”