Xi: Failed Reformer, Part II

A Reflection of Brookings Panel Discussion on Prospects of Political Reform

“With great power, comes great responsibility,” Uncle Ben to Peter Parker.

“其二 [三观论],权力观是“双刃剑”… 真正做到“权为民所赋、权为民所用”,” 习近平.

“Second, power is a double-edged sword…[For this reason, power is best summed up by two phrases], power is bestowed by the people, and power is used for the people,” Xi Jinping in a speech delivered to the Central Party School on September 1, 2010.

When I was travelling in rural Guangxi province, I once struck up a conversation with an engineering graduate from a top 10 university in China. At first, he wondered simply who I was and why I was travelling so far outside the destinations usually trafficked by foreigners. But when I told him I was a graduate student at Peking University’s School of Government and on track to continue my studies at LSE after I successfully defended my thesis, the conversation quickly drifted to more sensitive topics. He parroted the official Party line1 that China’s governance is different from America’s in that it operates like a machine, and that it is incorruptible (廉洁). Perhaps betraying every unwritten rule on face, I told him flatly this was nonsense and that he only believed it because he has spent too much time studying the metaphor at university. I feel like the peasants I noticed herding mules that day likely understood the stark realities of China’s governance better than he did.

While the outburst certainly didn’t have the intended effect, I believed I was channeling a deeper wisdom that the first step to understanding is opening your eyes, observing the world as it is not as it is depicted in stylized abstractions. In March 2018, I translated an article by the Renmin University economist, Xiang Songzuo, who similarly argued the first thing people who doubt the nature of China’s domestic problems should do is go to the countryside or even the outskirts of Beijing. On those edges of the city outside the fifth ring road, you will find hordes of desperate migrants and rural folks mistreated by local tyrants2, who nonetheless sufficiently believe in the benevolence of the central government to petition and correct abuses elsewhere, Xiang implied.

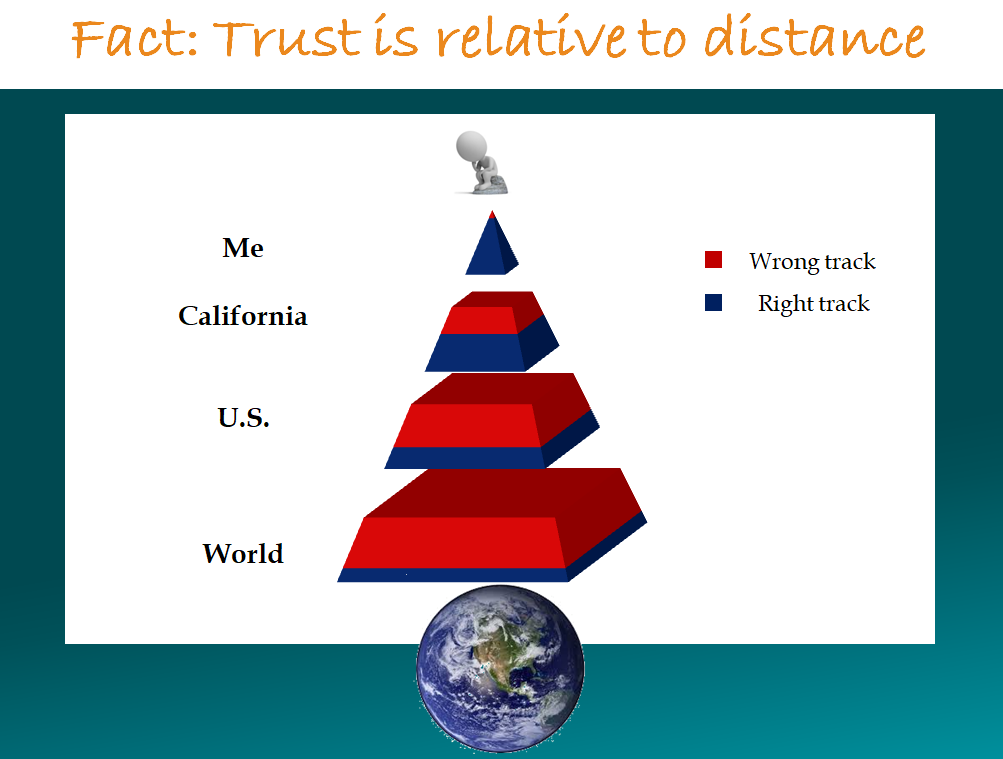

I was also thinking of the UCSB dissertation written by my thesis supervisor at PKU, Liu Yanjun, on the divided leviathan, which he revisited last year in The China Review. In both articles, he emphasizes that there is a division between center and local governments, and that divide is exactly backwards from the expectation of many mature democracies. As he was putting the finishing touches on his dissertation in 2017, Liu may have encountered a UCSB lecture, where the journalist James Fallows recounted his observations from travelling across the U.S. in his plane. He had written about those observations in The Atlantic, and would later collect them into a book, Our Towns. Applying a journalist’s eye, Fallow’s argument is that while national media overwhelms the public with stories of dysfunctional Washington politics, an American renewal is occurring right under our noses because communities around the country are dynamically responding to local problems. He writes, "Many people are discouraged about America. But the closer they are to the action at home, the better they like what they see.” In the U.S., trust is relative to distance, as I would demonstrate using Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) polling data to the young leaders at the Panetta Institute for an old boss, Jim Mayer’s 2017 lecture (see graphic below). The principle is equally true for China, but trust flows in the opposite direction.

A Path Appears?—Between Totalitarian China and China Bogged Down

“Hope is like a path in the countryside. Originally, there is nothing – but as people walk this way again and again, a path appears,” Lu Xun, Chinese essayist.

I was reminded of this anecdote on the need for bottom-up accountability to overcome governance challenges after listening to two fantastic Brookings panels yesterday.

The first panel was chock full of insights, especially Tony Saich’s commentary on whether Xi Jinping represents a return to Mao. He echoed a remark from another discussant on the second panel, The Carter Center’s Yawei Liu. It depends which Mao you have in mind. The Mao of the Yan’an years, who argued for need for discipline, unity of thought, and elimination of rivals, hits the mark for the sharpest observers of Chinese elite politics. But as Mao’s power grew away from the Party, he realized that he could float above it, discovering that chaos could be instrumentally useful. Saich quoted a 1956 speech, which I was unfamiliar with but is consistent with his view of China’s place in the Marxist-Leninist tradition, “One day neither the CCP nor democratic parties will exist. It will be very pleasant.” Saich further noted that this is in stark contrast with President Xi, like Deng “a pragmatic Leninist”3, who speaks of Party atrophy with scorn. Adaptive pragmatism of China’s governance is a enduring historical legacy of guerrilla warfare at Yan’an, overcoming the rigid Leninist structures of its Soviet progenitors, the panelists suggested. However, Shambaugh articulated his dissent with this point in the second panel. He argued that since the fang/shou (loosening/tightening) cycle has went into dormancy stuck in shou without end, governance has reverted to the neo-totalitarian command-obey U-form leadership structure that spelled doom for the Soviet Union.

But, interestingly, the heart of the debate centered around neither the legacy of the revolutionary period nor from Xi to Stalin continuities but on the prospects of reform in the future. Chiefly, that debate was between Yawei Liu and David Shambaugh. Liu brought his long experience on China’s political reform to bear, reminding younger China watchers like myself that President Xi was not always thought to be a member of what Shambaugh calls the archconservative camp in his book, China’s Leaders. Even in 2010, after the tightening began as a result of a spike in domestic contention and the reverberating effects of the global financial crisis, then-Vice President Xi signaled to the Central Party School in a speech that he intended to ride President Hu’s wave of consultative reforms toward procedural democracy. It would be about power through the people, not merely serving the people.

The significance of that speech was not missed by many prominent Chinese intellectuals, including one prominent Party School theorist who has been recently excommunicated from the Party, Cai Xia. In a beautiful polemic on the evolution of China’s governance as a Long March from revolution to democracy, she cited that speech as representing the still unrealized promise of the recently selected Xi administration. Operating within a common intellectual tradition from Mao to Liang Qichao over dynastic cycles, she ultimately settles on the same basic observation as Amartya Sen. Catastrophes associated with the downward phases of dynastic cycles do not occur in democracies because they are protected by constitutional order, she wrote.

She would also preview her later criticism of President Xi that would get her into trouble with the Party, “They mouth the platitudes that power is the people’s, but in their hearts, they think, ‘power is mine’.” President Xi and Ambassdor Qin Gang’s platitudes draw on the legitimacy of democracy, recognizing the illusion is necessary to avoid the Soviet Union’s path, without any commitment to the underlying principles. In this critical view, the people-centered approach articulated in Xi’s New Development Philosophy is a lot of sound and fury signifying nothing:

As the old saying goes, ‘As vast as heaven and earth may be, the people always come first’….We will only have the right view of development and modernization if we follow a people-centered approach, insisting the development is for the people, reliant on the people, and that its fruits should be shared by the people.

The drift away from the early promise of political reform, betraying intellectuals like Cai Xia, should call to mind earlier episodes, Liu argues in his piece for the USCNPM. Zhao Ziyang’s reforms initiated in 1987 were tragically stalled by the Tiananmen student protests of 1989. The blueprint to institutionalize democracy with Chinese characteristics was moving headstrong until 2009, as John Thornton’s pre-GFC 2008 Foriegn Affairs essay describing his active role in the shaping the consultative democracy agenda demonstrates. Reading that essay today is like being transported to an uncanny alternate universe, where the contours of Chinese politics as studied by younger observers are broadly familiar but the overall impression is nonetheless radically different. The broadly familiar point mainly relates to the desire to move to a genuine rule of law with popularly recognized legitimacy, in no small part to blunt the metasizing effect of mass demonstrations in the mobile phone era. Legal scholar Taisu Zhang’s work on China’s “turn toward law”, as articulated in recent official party documents, resonates.

The uncanniness to the generation that remembers the Hu era as a fragment of history rather than lived experience relates to accountability. The rugged independence of commercialized domestic press and the freedom of movement for foreign press is increasingly unfamiliar in Xi’s New Era. Even the financial publications, like Caixin, vital for informed decision-making by China’s banking technocrats are losing their independence. And triumphalist China is growing increasingly bold in their rejection of visas to foreign journalists, merely to enter the country, to say nothing of freedom of movement within it.

That is not imply that there have been no successes. One thing Thornton discussed with China’s top brass was their ambition to reform the National People’s Congress (NPC). The CCP has largely followed through to the point that one scholar argues that this legislative body is a model of authoritarian responsiveness in his book, Making Autocracy Work.

Along these Whiggish lines, Thorton’s overall emphasis was the same as President Carter’s in a lecture at Emory University in February 2018. Thornton writes that there can be little doubt that China moved in the direction of liberty between 1998-2008 on issues ranging from the totalitarian control of hukou for rural migrants, to urban residents employed by their work units danwei, or the openness conveyed toward outsiders. Similarly, President Carter argued ten years later that direction remains unambiguously in favor of freedom of movement, and lifting controls on the command economy to allow people to keep what they earned. Even more decisively, there are the values the follow from these limited freedoms, engendering a spirit that better understands “the reasons for harmony, cooperation, and mutual respect.” What retrospective critiques like The China Fantasy fail to acknowledge is that during the most transformational period of China’s economic miracle, sweeping modernization in these areas did gain significant traction. In any case, President Carter was never under the illusion that differences between the two countries would evaporate. He explicitly stated that was never the basis of engagement policy made possible by normalization of relations, which remains one of the proudest achievements of his administration.

From the view of many respected China scholars, including Yawei Liu, the difficulty in China today is not a story of absolute regression, but of a crisis of success. With the success on the movement toward liberty, triumphalism follows that conflates liberty with democracy. Remarkably, at around the same time Vice President Xi was signaling his future intentions to Comrades at the Party School, Premier Wen Jiabao visited Fareed Zakaria’s CNN program. The fact that top leadership like Wen interviewed at all with foreign media in this era signifies just how much times have changed since the tipping point in Sino-U.S. relations4, Lawrence noted in the conversation.

Wen Jiabao of course is a famously liberal Party-man who remarked in this conversation that, “I believe that the [Chinese] people’s wishes and need for democracy are irresistible.” There are two contextual points that are worthy of note, however. The first is that he does not concede this point until Zakaria pushed him to weigh in not only on their personal liberty, but also their democratic freedom. As much as novice observers may pontificate on oriental despotism, there is nothing about China’s intellectual ecology that leave them allergic to this insight. The head of the School of Government at PKU when I attended in 2018-19, Yu Keping, once wrote in a 2006 essay, Democracy is a Good Thing:

Even with the best clothing and food, human personality is incomplete (implied reading: feels empty) without political rights.

The second point is not included in the clip, but was reported at the time he did the rounds on international media, in that he noted the strong headwinds he faced in deepening the agenda. Simply because the need for democracy is irresistible does not imply that it is inevitable, Premier Wen cautioned. Those headwinds included the growing inner-Party rivalry between the liberals headed by Zeng Qinghong and the archconservative camp, Victor Shih interpreted in 2010.

Shambaugh suggested in his panel that the disagreement that re-emerged during this period fundamentally related to different assessments over the causes of Soviet collapse. Were the causes directly related to Gorbachev’s economic and political reforms, perestroika and glasnost, or were they representative of underlying weakness that predate Gorbachev? Up until the late Hu period, the dominant narrative of Soviet collapse was in line with the Western perspective that the spectre that haunted the Communist world in 1989 was one of economic failure. In the era of the personal computer, China was still struggling to provide basic consumer goods to the point that the sight of a washing machine in central Beijing attracted crowds, Shambaugh revealed in his recent book. The goal of the Jiang-Zhu Rongji era after Deng jump-started reform following the Southern Tour in 1992 was to correct that error. The backlash has now come in the form of the neo-authoritarian camp, headed by Wang Huning, arguing that decadence is just as grave of a threat to ideological discipline on which Party stability depends as scarcity. As Shambaugh summarized in the conversation, prosperity without discipline is a recipe for disaster for a revolutionary Party that feigns belief in Marxism, while drowns in pervasive corruption and loses their grip on dysfunctional local party cells.

The neo-totalitarian impulse has now firmly imposed itself in ways that both threaten the market-conforming character of its governance model and will create political risks 15-20 years down the line. China today is even more aptly characterized as a fragile superpower than when Susan Shirk wrote the book during the Hu administration, Shambaugh asserted.

Though Shambaugh firmly—and at times viscerally—disagreed with Liu on the prospects for political reform, he opened the door to Liu’s suggestion of China’s once and future democracy. As the British naturalist David Attenborough reminded his Netflix audience, if something cannot be continued forever, it is by definition unsustainable. There remains the possibility that “a third scenario” currently only expressed as a recessive tendency could be observed in between totalitarianism and a bogged down China. The kicker in Liu’s written commentary is the rhetorical emphasis he places on the phrase “at least for now” by repeating it.

For this reason, the burden of proof is oddly higher for Shambaugh’s side of the argument. He needs to not only provide evidence that China is moving in a neo-totalitarian direction, but that mode of governance, when it is sufficiently “neo”, is more sustainable than it once was. This is increasingly an open question. Recently, I reviewed two giants of political economy, Acemoglu and Robinson’s book, The Narrow Corridor. That book accomplishes two of its objectives. A&R repeat the ancient point that liberty is precarious, while also contribute to the more novel notion that technology may favor tyranny. Under an AI-tocracy, governance may be made legible without society’s input.

This has immediate applications to China’s governance. Scholars who had previously emphasized the legacy of China’s adaptive pragmatism like Sebastian Heilman are now increasingly speaking of digital Leninism. More recently, Dimitar D. Gueorguiev wrote a piece for Noema promoting his book, Retrofitting Leninism, arguing the collusion of China’s surveillance capitalism has resumed some of the dimensions of The Cold War, including the famous calculation debate which once animated neoliberal thinkers like Frederick von Hayek at LSE.

I’m sure Shambaugh disagrees, and he may prove to be right conditional on how Chinese AI superpower develops over the next decade, but I found Yawei Liu’s “at least for now” refrain to be enlightening. Since 2009, the coincident events of my adolescent and adult life are zero-interest rate policy by the Fed and the reversal of the earlier political reform trajectory Liu and Lawrence look back on fondly. In each instance, they have disrupted the traditional tightening-loosening cycles and have to instead rely on extraordinary levers to sustain effective governance. The directions of course are different in that monetary policy has seen a period of loosening characterized by escalating plunder, while critics of China’s crony capitalism under Xi might characterize the CCP according to a similar logic of plunder, but instead appears to tighten without end.

I believe that the reasons why people are often simultaneously interested in financial markets and China extend beyond practical concerns like gaining global market share. The interest also reflects an unusual epistemological inclination when confronted with complex systems. When most people encounter a pattern, they expect that pattern to continue. This goes doubly for any pattern that has continued for more than a decade. The gifted analyst instead looks for all signs in the emerging cracks, which may end up reversing the supercycle. That task is a fool’s errand as complexity all but guarantees that the cracks that are found are not the ones that will prove decisive in sparking a sea change. The pursuit of this knowledge, while always imperfect, has a way of gaining an edge over other analysts who are merely looking for trends. In the data-driven profession of finance, there are too many harbingers of the current state of the market to list here. But the harbinger for China was arguably hiding in plain sight in Thortnon’s essay, arguing the consensus among China’s leaders at the time was when, not if, democracy would take root:

Others [among China’s leading cadres] predict that the process will take at least two more generational changes in the CCP's leadership -- a scenario that would place its advent around the year 2022.

Only one thing can be said to apply in equal measure to China’s elite politics and financial markets in 2022. Let the year of the wild rumpus begin.

While I did not directly ask him if he was a Party member, recent research on the psychological traits of Party members by Princeton’s Rory Truex suggests that the gregarious, ambitious young person I encountered on the bus that day was very likely a recent recruit into the Communist Party.

Referring to the central government’s obstacles to achieving pollution reduction targets as an “odd sort of dictatorship”, the British journalist, Jonathan Watts, wrote in a 2010 book that these middle-men between the people and the center have the real power in China’s government in that they can exercise arbitrary tyranny, calling them “mini-Maos”. Many Xi’s initiatives to rein in ideological discipline and inspections in the anti-corruption drive are about these mini-Maos.

See another panelist, David Shambaugh’s descriptions of China’s leaders.

Which Lampton’s 2015 speech underscores, predates Trump, and continues today under the Biden administration.