Hayek in Beijing

One Reading of The Ungovernable Society: A Genealogy of Authoritarian Liberalism

“The cultural contrasts were equally dramatic. Paris in 1729 was the city of light, the seat of the Enlightenment, the heavenly city of the eighteenth-century philosophers. Its great libraries…were among the best in the world. Its elegant salons set the intellectual fashion for enlightened people everywhere. At the same time Paris was also a capital of despotic darkness. It was the controlling center of an absolutism that ruled by terror, cunning, and brutal force. High above the city’s fabled rooftops rose the walls of the Bastille, where state prisoners were held for life without the slightest shadow of legality…In the center of the city was the Place Greve, where huge crowds gathered every week before the City Hall to watch obscene tortures inflicted upon shrieking victims,” David Hackett Fisher in The Great Wave.

“Yesterday’s hopeful doctrine and today’s dismal reality could not be farther apart and Tocqueville’s sentence would seem to be more applicable to current Latin American experience if it read instead: ‘A close tie and a necessary relation exist between these two things: torture and industry,” Albert Hirschman, rebutting the old idea of deux commerce.

“Is it surprising that the cellular prison, with its regular chronologies, forced labour, its authorities of surveillance and registration, its experts in normality, who continue and multiply the functions of the judge, should have become the modern instrument of penalty? Is it surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks, hospitals, which all resemble prisons?” Michel Foucault.

The Strange Silence After an Earthquake

Lately, I’ve been drawn to books on the biggest themes because I have the imprecise sense that the world is violently shifting underneath our feet. To be sure, these tremors have been percolating toward the surface for a while now, but until released hadn’t triggered an earthquake that signals a decisive change in the guard. I’ve noticed that my thoughts on this subject often follow a similar pattern; collecting isolated observations over the last several months until I serendipitously encounter an explanation that pieces them all together. For me, this SupChina interview with Ann-Stevenson-Yang was nothing short of an intellectual earthquake.

By no coincidence, “China” was the loci of that thread as it is an essential entry point(s) to process the deglobalization earthquake. Hanging on a thread since the GFC, the neoliberal dream has now been officially deferred.1 Armed with this intuition, I find it a little strange that the books I’ve been picking up to follow my in media res curiosity flatly refuse to bring China into their Grand Narrative. For example, this is all the curiosity the authors of The End of End of History could summon on China, no more than an invitation, “[Anti-corruption in Latin America] was viewed as a depoliticized manner of criticizing the government. One might note that anti-corruption’s currency in contemporary China might be explained in the same way.”

I eagerly hope Jeremy Wallace accepts the invitation in his forthcoming book on China’s neopolitical turn under Xi, Seeking Truth and Hiding Facts. Post-liberalism in Beijing? After all, they have assembled an equally broad rainbow coalition— from neo-Maoists covered in Jude Blanchette’s New Red Guards, to the sidelined market liberals like Mao Yushi and Wu Jinglian, to the involuted generation who are initiating a 1966 in reverse movement to return and rediscover Daoist cultural values in the countryside— against the managerial revolution. For the American analogue, Gerstle’s main claim in a recent book on neoliberalism concerns its protean character— what the worldview lacks in coherence is compensated with staying power.

Neither Biden nor Xi is the general of this panoply of characters. But Xi’s strategic orientation with respect to it is more adversarial as it represents a potential threat to ideological discipline, the sustained efforts to organize social actors around one brain, Frederick the Great once characterized. The authors of a book on environmental authoritarianism argue that the zenith of techno-populism, a political movement ripe for the 2010’s interregnum but whose theoretical underpinnings date back to the 1980’s, is not to be found in Italy as the Bunga crew would lead you to believe, but China. They write that it is the solution to the global post-political threat:

“What our investigation makes abundantly clear is that technologies not only embody a full suite of political qualities, but also expand the scope of political control and intensify the penetration of state into society. The techno-political complex thus constitutes an indispensable element in the state’s pursuit and realization of its political ambitions,” Shapiro and Li.

The fate of that ambition, the techno-utopianism of Xi Jinping thought, might be the key question on which the 21st century hinges. Like Modi’s India, the thing to fear is not so much success but failure the deliver growth through a GPT transformation to transgress the limits of its export crutch. As Michael Pettis emphasizes, it is the favored solution out of its economic impasse, one that political elites rate as attractive, but viewed skeptically by economic analysts as unrealistic. Hochuli seems uniquely qualified to turn the Brazilianization prophecy emanating from the triumph of broken growth promises to the core of the global economy. Prompted by an interview he gave to the CCP’s mouthpiece, The Global Times, I asked him once if the deferred dreams of the global middle classes who feel increasingly shut-out by corrupt elites are generalizable there. He frankly replied that he doesn’t have any business making any claim on China. Other writers acknowledge they can’t pretend to know the future of neoliberalism with Chinese characteristics, but appreciate the significance of the question, taking an active role to bring people in who are qualified:

Make no mistake—their reluctance is a positive development. For centuries, Westerners who did not speak the language had an oriental gaze, which did nothing to advance understanding. My suggestion is that perhaps the pendulum has swung too far the other way, where erudite scholars who are perfectly capable of making informed inferences retreat from the discussion because they fear stepping on another’s silo. I fear that even someone of Bertrand Russell’s stature would have not have written an observational and speculative book like The Problem of China if he lived today.

Echoing this point, Rhodium’s Jordan Schneider composed a book review thread on how all scholastic disciplines must strike a balance between formalism without losing sight of why people become motivated to enter study. Political science without power, economics without well-being, and China studies without history are all marches toward irrelevance. Counting is it turns out not a schoolboy’s exercise. The counters often don’t count what matters, and what they do count often doesn’t measure up. Examples abound, but two cases on each end of Wallace’s phrase seem particularly salient at the moment—inflation targeting and the shockingly small observable welfare effects of moderate inflation.

The failure that haunts the elite stewards of global economy in 2022 isn’t to suggest there isn’t value to be had in counting. Counting might be an Iron Cage, but one that is vital because it “brings everything to a certainty which before floated in the mind indefinitely,” (qtd. in The Great Wave pg. xv). Beware of siding on the metaphysical orientation that everything is perpetually shifting. That is also a march into the wilderness, Paul Krugman once reflected on Albert Hirschman’s banishment from the development economics profession. Think as you like, but behave like others, so goes the old adage.

Observers who lack discipline to stay focused on any particular area are susceptible to imposter syndrome I believe is new to the Information Age. As one of the wisest observers on FinTwit recently recalled, people who refuse to prioritize often feel like his childhood farm dog who, upon discovering 40 rats previously hidden within a bin, quixotically chases all at once. Byton Hobart similarly asked on the Bretton Goods podcast last year: how does one distinguish between a genuine polymath and someone who by the Dunning-Kruger effect is convinced that his superficial knowledge in a range of topics qualifies? I think Supreme Court Justice Stewart Potter’s ad hoc test applies, “I know it when it I see it.”2 Bertrand Russell passes, Richard Hanania does not. I might add that I also prefer the Bertrand Russell types over experts who prefer excessively complicated explanations of reality for the sole purpose of signaling their expertise. They are Ersatz intellectuals, belonging to the varieties of stupidity relating to social vulnerabilities rather than dysfunctional hardware.

Failure of Grand Steerage: Keynes passes the Baton to Hayek (no, not that Hayek)

It’s possible that I should treat @shortl2021’s fable on the farm dog’s failed attempts to catch rats more seriously. But I am too committed to the belief that interesting work comes from looking for connections others are not considering. Admittedly, in attempting to combine the strands relating to the limits of China’s governance as grand steerage and a similar tale in the Western neoliberal order, I will reveal I lack a sufficient knowledge base in both.

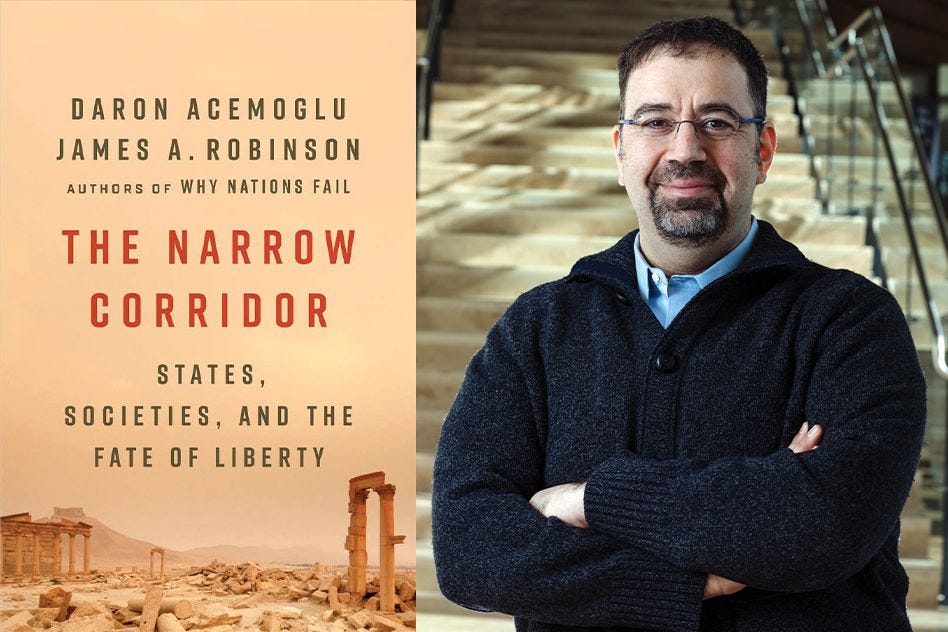

Every once in a while I pick up a book where the impressions are so loud I feel compelled to adjudicate them into a Grand Narrative. The Ungovernable Society: A Genealogy of Authoritarian Liberalism by the French scholar, Gregoire Chamayou, was such a book. China is not mentioned in the book, except indirectly through the detour of Latin America. Note the strikethrough in the above Hirschman quote on deux commerce and the opening hook in my essay on possibility that overconcentration of power may erode state capacity in China too. I recognize that essay was absurd when I read The Narrow Corridor last November, but is much less absurd in light of China’s zero-Covid induced governance implosion, a catastrophic success.

Here is my attempt. The arguments center around which apparition you believe is currently roaming down Chang’an Avenue in central Beijing, each offering a competing vision of neoliberalism, Keynes or Hayek. Their political philosophies, in turn, date back to the decisive event of Western modernity, the French Revolution. The live struggle of these competing ideas is likely what Zhou Enlai meant when he quipped that the overall effect of the French Revolution is still too soon to tell. Likewise, Tooze indicated in January the British historian Herbert Butterfield captured the spirit of British intellectual life. Knowing where you stand on this issue remains a rite of passage, Butterfield once opined. The liberals celebrate the 1910 People’s budget and Beveridge welfare program as a victory of reform without the rivers of blood of revolution (Bertrand Russell was one).

The conservatives are revanchists valorizing Thatcher as a neo-Victorian revival. Make Britain Great Again. They skip over the flawed but vital story3 David Edgerton tells on how a once self-reliant Britain built in Beveridge’s image was reduced to a financial junkie totally reliant on the City of London. Americans should look on that story with open eyes. Neo-Victorians everywhere are obsessed with ordering, so as to guard against the slide to Jacobin tyranny. A compulsive vigilance “to dedicating our wealth and soundest youth to suppressing revolt against the existing order everywhere,” Will and Ariel Durant interpreted of the Victorian period in The Lessons of History. Their concern is feigned, however, as they are indifferent to all other forms of tyranny.

Perhaps Zhou Enlai anticipated that the prevailing East wind of the Asian century would pick up this historical drama to Beijing. As Tooze tells it, Keynes is roaming Beijing as Party elites in regulatory ministries know perfectly well how to address what Burke called “the finest problem of legislation”, sorting the Agenda, those questions which regime stability depends, and the non-Agenda, those issues which may not trivial, and in fact may be fluidly reconstituted into the Agenda, but can be safely ignored.4 In short, Rory Truex’s authoritative book demonstrating authoritarian representation is no contradiction in terms, Making Autocracy Work, is a testament to the neoliberal logic guiding and containing Xi’s China which might otherwise falter.

But what if Tooze’s neoliberal is the wrong neoliberal? Instead, there lurks a two-face, one part immured within the compound at Zhongnanhai and the other part wandering further out in the technological and research centers near Zhongguancun in the Haidian district. That two-face is Hayek. The two face pattern5 is in marked contrast with Keynes and relates to Hayek’s project as depolitization. Chamayou traces that lineage to Carl Schmitt on the diffraction of the ethico-economic, and in the process, debasing each, “Once emanating from opposite poles, they tend to annihilate the political…end up with…demilitarized and depoliticized concepts.” “Demilitarized” is an interesting word— Tooze’s extended critique with Hochuli at a live event in NYC focused on the anachronism of reviving “the masses”, a concept which has its origins in military symbols, Tooze noted. The parallel PMC transformation is to be found in Rory Truex’s research on personality profiles of Party members that, given the Party’s grooming according to sociability, it is difficult to imagine the successive steps which would incite a Tiananmen-like mass rebellion.6 The great leap in opinion steerage since 1989 precludes that possibility, though he invites his Princeton students to prove him wrong.

Keynes had an ethico-economic unity to his thought, which is difficult for the modern sensibility to understand and why Robert Hockett’s efforts to constructively retrieve those reconstituted elements are so laudable. Hayek had no such unity. In his writing and public interviews, Bertrand Russell liked to emphasize that it is sometimes necessary to separately evaluate a great historical figure on moral and intellectual terms. As a moral philosopher, Hayek was abhorrent. As a thinker who laid the prophecy of the short 20th century, he was brilliant. Obsessed with the inexorable devolution of state control to totalitarian tyranny, “bad” Hayek is loud and clear, “A dictatorship may be a necessary system during a transitional period…In such circumstances, it is practically inevitable for someone to have absolute powers.”

Chinese Party School intellectuals, if not Xi Jinping himself, have for a long time insisted that the “ultimate aim” of the CCP is democracy. They are channeling Sun Yat-sen’s idea of tutelage but only so long as China remains a sheet of loose sand. After all, democracy is a good thing, wrote the dean of my alma mater, Yu Keping, in 2006. 2006 was a long time ago. Tutelage has been rejected, and democracy relegated to the non-Agenda. Instead, local officials under Xi are dictated by “bad” Hayek dedicating wealth and soundest youth in form of stability maintenance compelled by the paralyzing fear of the inert masses. This totalitarian drift from authoritarian liberalism is a long-running trend, which has recently went into sharp relief as COVID surveillance and quarantines have revealed a new dimension.

And elsewhere, they fail to appreciate “good” Hayek’s gospel of decentralization, believing that creativity can be neither directed nor controlled but emerges spontaneously beyond the planner’s comprehension. At LSE, Hirschman once admired this side of Hayek. Deng Xiaoping’s mantra of governance, crossing the river by feeling the stones, intuited Hirschman’s practical interpretation without Hayekian dogma.

China’s Future: Hayekian Bears & Keynesian Bulls

As a failed reformer, President Xi appears to claim that authoritarian liberalism was well and good for the prior period of Reform, but it would be unwise to unflinchingly commit when the external environment is rapidly abandoning those principles. I tell you simply climb the Great Fire Wall to read about Western populism and disorderly accumulation of capital, and you will find all the evidence you need, he might say. Something more is required to forestall any potential radicalizations of society which might jeopardize its position in the bizarro corridor. While different from the liberal democratic corridor, possibly even sui generis, it can also be narrowed in ways that threaten regime stability.

If pursued, they will have left even Hayek behind, though the lineage can be unmistakably traced to the common anxiety for the proles. There has in short been a third movement, producing a bastard neoliberalism that is recognizable to neither Keynes nor Hayek. A phase transition would occur, Chamayou writes reviewing the Frankfurt School intellectuals who instinctually resisted neopathy, “A fascist capitalism is not the mere addition of an attribute to a substrate that remains identical despite an incidental modification…When [emergence] happens…we suddenly find that we are in another world.” The task of demarcating the Agenda from non-Agenda by rational means would be abandoned. They would be too paralyzed by petrifying fear for that. Hayek would respond with horror to his Frankenstein’s creation, a totalitarian metamorphosis springing from underestimating the propensity for his authoritarian face to consume the liberal one.

And yet, AI-tocracy is more stable than bastard neoliberalism elsewhere. Political scientist Richard Rose noted during the peak of the 70’s ungovernability crisis there is nothing inherently unstable about a regime based exclusively on the first primitive face of power. In fact, people are often so stricken with Old Testament morality they observe an explicit preference for coercion, he noted. According to his theory of the case, totalitarianism is a system in equilibrium. Those speculating totalitarianism will get bogged down against a natural limit or hoping for a simultaneous turn to liberalism on each side of the Pacific are waiting for Godot. Breaking this spell in the Age of the Strongman will prove difficult: though He slay me, yet I Trust Him.

The second reason pertains to the policy trace of China’s reform trajectory. Each of the revolutions that preceded the third movement were not entirely displaced. Like the West’s notional commitment to its neoliberal order alongside retreating expertise to credibly implement, China’s historical political economy is marked by contestations that make a mockery of the Marxist notion of successor regimes. Both the revolutionary legacy with unrivaled capacity to steer elites and technocratic-rational aspects that Tooze emphasizes, synthesized in the Heilmann & Perry thesis, make China a very different kind of state from other distantly related members of the authoritarian liberal genus in Latin America.

Still, superstar economist Paul Samuelson’s 1980 omen wasn’t too far off base. More of the world is starting to look like Latin America. It just took 20 additional years for his vision to bear fruit. The natural question that follows: a coming Chinese debt crisis? Precisely one of the scenarios posed by one of the sharpest minds on the Chinese economy, Bert Hoffman, in a recent thread and presentation. My tentative answer is if you see Hayek’s ghost, you will take the bear position and believe the limited reform path is likely, and debt crisis is possible. If you still see Keynes in China, sipping tea while marveling at the products of globalization, you believe the baseline path is likely, and the comprehensive reform path is possible. The comprehensive reform path, which would see the emergence of an economic hegemon every bit as dominant as post-WWII U.S., should be celebrated, not preempted.

But the triumph of broken growth promises is the more likely challenge for the world order in the near term, because, fundamentally, our methods of social and political organization have not kept pace with technological progress, and stubbornly resist the reforms that would align them. In this respect, neither Keynes nor Hayek have survived China’s third movement. They too are living in Roberto Unger’s Brazilianized world.

Langston Hughes’ linked poem, Harlem, structured as a series of question crescendoing up to the final question is potentially relevant here. In the 2010’s interregnum, we have covered the drying, festering, rotting, and even removed some of the syrupy excess. Only one question is left. Does a dream deferred explode?

Responding to the Supreme Court draft opinion leak, I believe it was Matt Klein who said that law is is, at its core, bullshit. I tend to agree.

This bit is a digression anyways, so will have to save why it is flawed for a future entry. Suffice it to say Edgerton downplays the crisis of the 70’s.

It might be more accurate to say that the ideas of dead Chinese philosophers have influenced standard Keynesianism, as his Agenda/Non-Agenda distinction was in part inspired by his incredibly wide reading. Weber writes in a footnote to How China Escaped Shock Therapy, “In light of Keynes’ 1912 review of Chen Huan-Chang…the question emerges whether Keynes was inspired by ancient Chinese economic thinking.” As is reliably the case with interactions between East and West, what is often assumed to be an instance of convergent evolution, reaching a common end from different starting points, is uncovered as divergent evolution with even the slightest scrutiny.

One of the surprising things about Chamayou’s book is how all the prominent authors from Thomas Schelling to Richard Rose I studied at LSE were moral-intellectual two-faces. They contributed to great insight, but also made remarks that were blatantly authoritarian. I wonder if there will come a day when these statements are problematized rather than ignored, much in the same way American history curricula has been revamped.

One thinker who was not a two-face, but a total anti-Keynes who birthed the bastard neoliberalism which would come to dominate GOP orthodoxy was Milton Friedman. He was in favor of starving the beast of the fiscal state, explicitly favoring deficits that would come to dominate during the Reagan, Bush, and Trump presidencies. In this light, the Nordquist pledge is straight from the Friedman playbook, “The reason a balanced budget is important is primarily for political, not economic reasons; to make sure that if Congress is going to vote for higher spending, it must also vote for higher taxes.” Severing the link was key to Tooze’s hopeful argument in The New Statesman for a green fiscal state in the Build Back Better push last year.

As the Chinese legal scholars Carl Minzner and Neyson Mahboubi Twitter gamble whether Beijing would experience a “Shanghai-style lockdown” demonstrates, there are some legal semantics with words like “Tiananmen-style rebellion”. I think to qualify as Tiananmen-style it would have to show a similar pattern of contagion, involving many Chinese cities all at same time and not be contained to students and intellectuals.