A few days ago, Boris got the majority in Parliament he so coveted. I may be misinterpreting Boris’ political programme in much the same way many were duped by President Trump’s moderate rhetoric, but I feel that the prevailing mood on the Left is more alarmist than it needs to be.

Monibot’s remark on Democracy Now that the British election result is a tragedy to anyone who hopes for justice fits into that category. In a literal way, I of course think the progressive left is right. Even moderate conservatives will be extremely unlikely to deliver on climate action, to say nothing of historically marginalized communities. And the Tories are unlikely to provide the moderate and stable leadership that the writer Andrew Sullivan ascribes to Boris Johnson’s political strategy to co-opt the radical right in much the same way Benjamin Disraeli and his Social Democratic counterparts did over a century ago for the radical left. The reason for my pessimism is the relationship between the radical right and political opportunists is far more mutualistic than the relationship to power and the revolutionary left ever was. So long as Boris’ intention is entirely limited to maintaining power, he may find it easier to jump inside the belly of the tiger rather than reigning in its more bestial instincts.

But overall, I am incredibly disappointed with reaction of the left in the sense that critical reflection of existing political strategies is almost completely absent from their interpretations of the British election result. There are two reaction one reflexive and the other revisionist. The reflexive reaction is that Corbyn’s Labor Party has simply drifted too far to the left to achieve any mainstream support from voters. Labour members, fresh off their academic careers in critical theory and sociology, have hijacked the party from its working class roots. The revisionist response, represented well by both guests on Democracy Now, is that there are two Corbyns, Corbyn the monster and real existing Corbynism. The media projected dark fantasies of anti-Semitism and wealth expropriation to a Labor Party Manifesto that is solidly within the bounds of conventional social democratic governance, prior to the madness of the neoliberal era dictated by unrestrained financial capital.

Elements of both accounts are correct, but only when qualified. The Labor Party has in fact drifted too far left to secure the same coalition of working class voters in Wales and the Midlands, and the media is engaged in a systemic assault on the more “radical” notions embedded within their programme. But Corbyn did not drift too far on economics, or at least that is not what prevented Labor from staying afloat.

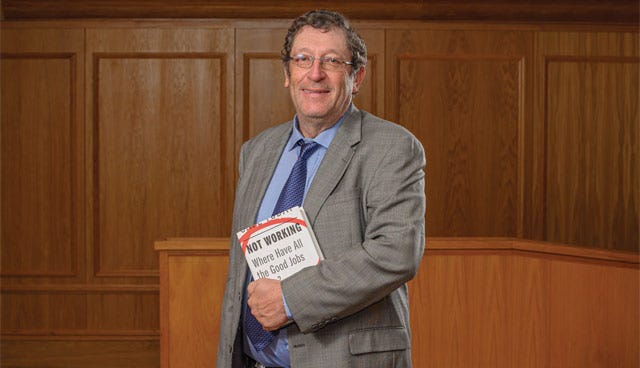

To explain what I mean by this, the British central bank economist Blanchflower’s book on the underlying problems within Anglo-American capitalism is immensely clarifying. The motivation for the book is that he was perplexed by the Great Recession represented an epistemological break for capitalism writ large. After all, advanced economies, by virtue of the wealth they have accumulated should be able to weather brief periods where economic output declines.

He provides a couple of reasons for the mounting fractures within contemporary capitalism, including the fact that the weakest members of our society were ultimately forced to bear the brunt of austerity. That fact represents a triumph of injustice, a product of the philosopher John Rawls’ worst nightmares. Yet it was not just the way we dealt with the crisis which engendered populist uprisings. If we are being truly honest with the underlying data, we cannot overlook the economic privation for the weakest members of our societies predates the crisis; the humiliating response to the crisis was merely a catalyst.

Keynes writes prophetically on the nature of popular discontent in The Economic Consequences of the Peace, “Economic privation proceeds by easy stages, so long as men suffer it patiently the outside world cares very little. Life proceeds somehow until the limits of human endurance is reached and counsels of despair and madness stir sufferers from lethargy….He listens to whatever instructions of hope, illusion, or revenge is carried to them.” I hope that Keynes is not quite the oracle he is often made out to be. As he predicted, body politics that suffer from this condition will be visited by the ghosts of hope and illusion, encapsulated in the promise of Obamaism and the fear of Trumpism. But so far, Americans have been fortunate to have staved off the ghost of revenge, which I fear is still to come.

Blanchflower persuasively demonstrates that Anglo-American capitalism’s reproduction depends on insecurity. Deviations from full employment are not a bug, but a feature of this model of capitalism. The insecurity so many face provides a window to the populist phenomenon, but one must look through the correct window. Marxist analysis of the kind favored by the intellectual class of the Labour Party is that mass insecurity will weaken inter-class AND national solidarity. Fraying national bonds will encourage workers of the world to search for new bonds with workers in other nations.

As it turns out, this interpretation is only half right. The Great Recession made a mockery of class solidarity, as Blanchflower underscores in the conceit at the heart of the Bank of England’s proclamation that “we are all in this together”. Paradoxically, national solidarity strengthened in the midst of the crisis.

I can only speculate as to why this might be the case, but I have to say, the psychological research on demoralization is a promising avenue of understanding. Two researchers writing on nuclear proliferation of the 1960’s highlight the psychology involved, “collective defenses, such as national solidarity…often impede organized activity intended to cope with the threat itself”, concluding “that what may appear, superficially, as a turn toward solidarity is actually a most precarious state of morale.” The Left may want to live in a world where human psychology was fundamentally different and unproductive collective defenses did not exist, but we must come to accept the world as it is.

Coming to terms with that world means we must develop our own vision of progressive nationalism. If we fail to do so, the Fascists will do it for us, offering narratives of revenge Keynes warned of. Labor activists and their Democratic counterparts across the Atlantic had moved well outside the cultural mainstream in that they believe their pasts are irredeemable, a belief that voters do not share. That past is objectively brutal and genocidal, but self-flagellating postures are not appealing to voters, and I think it explains the revulsion to Corbyn in Neil Kinnock’s former district, a Labour stronghold that switched to the Conservatives.

The Labour Party would be much better served if they rebranded the party as a nationalist vehicle, in much the same way left parties in Greece and Spain have already done. That message varies across national context, but the progressive intent is the same everywhere. What nationalism believes—strangers can come together across difference in pursuit of common objectives— is not wholly true, but it may become true if it is believed. So long as it expels the anti-Semitic fringe from its ranks, Labour is in a much better position to deliver this message of “One Nation” solidarity than the Tories because they are not forced to rely on blood and soil ideologues who are contemptuous of strangers. In short, nationalism, conventionally thought of as a barrier to true precariat solidarity, can instead be used as the raw material to build affective bonds to better realize that nationalism, and in the process end insecurity.