Climate Justice as Overcoming the Dark Forces of Time and Ignorance

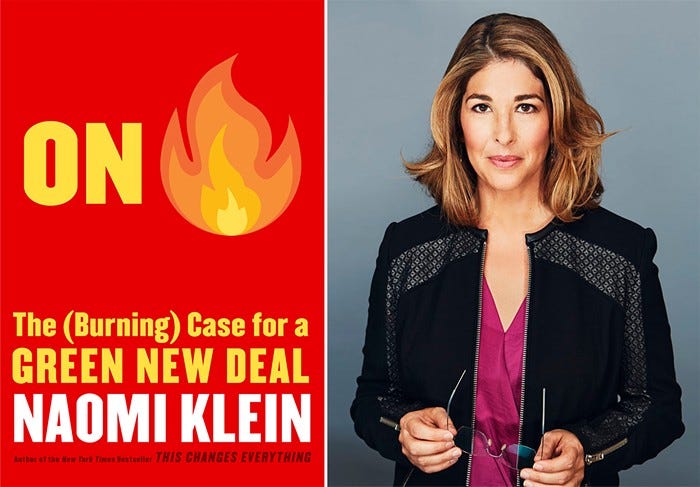

A Review of On Fire by Naomi Klein

I just finished reading Naomi Klein’s On Fire: The Burning Case for the Green New Deal. I have to admit that Klein is powerful advocate for justice, and I find many of the key claims about climate justice to be intriguing. But part of me is terrified that her solutions to the climate crisis are right. Reviving radical democracy that is practical (read: aligned with the threat), pluralistic, participatory, and provisional is our only hope to ensure that the world does not muddle into a great conflagration. Rhetoric of wartime mobilization notwithstanding, we are already too late to dispel and conquer the climate crisis, but we could manage and live with it through collective action.

The reason why I am terrified of the nature of her proposal is I believe she is accurate and share the NYT columnists view that human nature is not well-equipped to deal with the threat. Rather than the tendency to heavily discount events far into the future, I would like to focus on a different aspect of human nature—the tendency to desire alienated forms of organization. Most of us do not want to spend our leisure time in committee meetings. We would rather write, make art, watch Netflix, and consume dumb (but amusing) internet content. The democratic left may find that the public does not usually resent the alienated bodies that make decisions pertaining to the future governance of global capitalism as much as they claim to.

Nonetheless, I would be remiss to characterize the desire to submit to alienation as a static quality of human nature. Klein is especially perceptive in the conclusion of Capitalism vs. The Climate essay on this point. Culture is fluid. The hierchist and individualistic bias that currently prevail in the Anglosphere could give way to an egalitarian and communitarian ethos should it dawn on the public that climate change is an emergency. All that is solid, if given time, does in fact melt into the air. The question for climate activists is how to accelerate the melting of deleterious social constructs that prevent climate action along collective lines.

The added complexity is that the activist community is not the only set of actors attempting acceleration. The success of neoliberal capitalism is that it has promoted so much acclerationism that it has gone supernova, bringing to fruition Thatcher’s famous proclamation, then only an aspiration, that society does not exist. We are no greater than a collection of autonomous individuals and nuclear families participating in the market.

The atomizing supernova has of course backfired in a spectacular fashion in the rise of the far right eco-fascists who also embrace the accelerationism to align reality with their hateful and grotesque worldview. Both forces—destabilizing aspects of unfettered global capitalism and violent eco-fascists—contribute to the notion that the world is a dangerous place, solidifying the need for hierarchy as well as breeding cynicism about the possibility of building a truly egalitarian community.

Progressives of course could restrain global financial capital along the lines that Ann Pettifor recommends and offer democratic publics everywhere a source of hope. However, that source of hope will only ignite if we mainstream the climate movement to achieve broader social and economic goals. Progressives will have to convince people that proponents of the Green New Deal are the only politicians who do not tread in the waters of delusion.

The divide is not between the right and left moral foundations —fairness or authority, caring or purity—but our terrestrial reality or calamitous fantasies. An intersectional movement of the kind Klein envisions would go a long way to overcoming the obscurity of environmental parties Latour worries about, and move toward his vision of how politics ought to be constituted in the 21st century. This political project may very well ignite a counter-acceleration against the dark forces of time and ignorance to transform their vicious cycle into a virtuous cycle, which may also go supernova.

I have long worried about American responses to the climate crisis. In all crises, our better angels ultimately rise to the occasion, but only after visible signs of injustice reach our hearts and minds. America didn’t take a stand against slavery until the national trauma of the civil war was well under way. America didn’t enter either world war until civilians were attacked. Americans didn’t give black people their voting rights until we saw on our television screens images of civil rights protestors getting their heads bashed in and assaulted by water cannons.

Americans are uniquely suited to redressing injustice, or as the French observer Tocqueville once remarked “correcting our faults”, but we are also uniquely limited due to physical and psychological distance in our ability to acknowledge the principle that injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. Americans have built-in barriers to understanding the interlocking mutuality that defines the human condition. Here’s to hoping the Green New Deal and Klein’s solidaristic vision for climate activism unlocks America’s potential.