A New Kind of Politics for the 21st Century

Reviews of Down to Earth and And the Weak Suffer What They Must?

I have been quite busy and have not had the opportunity to reflect on two books I’ve read recently. The first book, Down to Earth by Bruno Latour, was recommended by Rev. James Walters at the LSE Faith Centre, and I ended up spending a few hours in the British Library delving into this deeply philosophical book. The second book, And the Weak Suffer What they Must?, is about the Eurozone crisis rather than the climate emergency, but they nonetheless have interesting points of convergence.

Latour contrasts the current model of globalization with a positive vision for the future called globalization plus. The key difference is that globalization plus becomes less parochial through pluralism that takes into account many different cultures and beings, while globalization minus is an inexorable force toward homogenization. To make this point a bit more concrete in my head, I connected this concept to a random article on Olive Garden as opposed to a dynamic cultural center—both diminish the importance of place, but only one vision does so through standardization to ensure that an Olive Garden in Sacramento is no different than in Des Moines.

Here, he brings up an interesting twist to the key arguments outlined by Karl Polanyi in The Great Transformation concerning protection from market forces. Latour notes that Polanyi is accurate to state that society is justified in protecting itself against homogenizing attacks, but his analysis was not as prescient as some commentators, from Joseph Stiglitz to Robert Kuttner, claim it is. To Latour, Polonyi neglected the possibility that the Earth itself could seek protection from the market forces fueling the climate crisis:

Polanyi overestimated society’s efforts at protection from marketization because he was counting on support from [solely] human actors and their awareness for the limits of markets… Polanyi could not have anticipated the addition of powerful forces of resistance thrust into class conflicts capable of transforming the stakes.

In short, the climate crisis has the potential to change the paradigm governing politics in the same way that the French Revolution changed the aristocratic and clerical prerogatives of the Old Regime. At some point this century, the right/left divide will be thrown into the ash bin of history to be replaced by a new vector— terrestrial and out-of-this world— the latter typified perfectly in Trump’s brand of theatrical politics.

This brings me to Latour’s key claim and my main take away from the book. The system of production is in fundamental contradiction with the system of engenderment. The two systems have distinct governing principles as well as the role they assign to humanity. Engenderment requires agency from all human actors because humanity’s role is central, while production requires dependency because humanity’s role is distributed. That is to say, it differs depending on your place in it. The author argues that a system of engenderment is dominantly preferred to that of production because it maximizes the possibility of confrontation from a range of animate beings and multiplies the sources of good trouble.

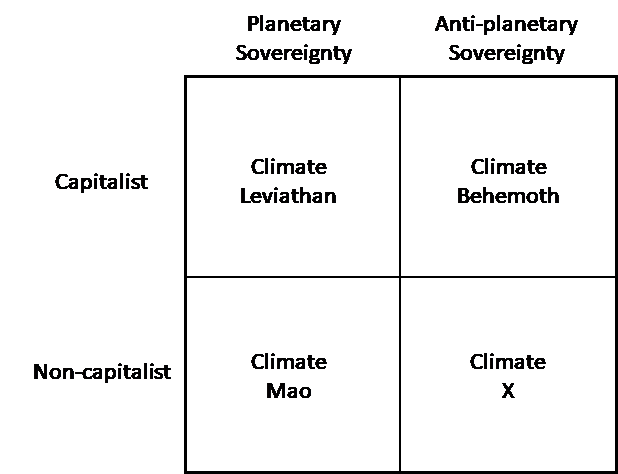

Moreover, that system offers a radically different epistemology and form of politics that is not merely interested in producing goods for humans, but engendering terrestrials of all kinds. This point on engenderment dovetails nicely with the argument for Climate X in Climate Leviathan. Mann and Wainwright warn of the dangers of a hierarchical climate regime administered by the world’s capitalist powers as well as the more distant possibility of a climate regime governed along leftist precepts but remains hierarchical. They write that the concept of sovereignty, or the prerogative to rule over rather than with, is misguided in a world shaped by climate upheaval, “This division is only possible on a foundation of a more fundamental, prior distinction between humans and nature, between lives and life, and humans and humanity.” Monocentric hierarchies are inadequate for engendering the emergent reactions needed to cope with the climate emergency, and only a polycentric system will simultaneously provide the requisite room for all terrestrials and recognize the mutuality of life. The solution is neither to curtail freedoms through Climate Leviathan nor Climate Mao because that will only erode the already tenuous grasp on social trust, but to foster the social arrangements that encourage freedom as the recognition of necessity.

Keynes once wrote that every man of action is the slave of some defunct academic scribbler. I believe Latour is one of those academic scribblers. Another way of interpreting the title of his book other than a common recognition to protect the place we all coinhabit is the imperative to move back to reality and ward off the fantasies offered by the emerging out-of-this-world political forces. Fantasy is perhaps the biggest obstacle to climate action, and we needed to be brought back down to Earth so as to be better aware of our own limits. This is the political project of the upcoming century.

For the second part of this journal entry, I will turn my attention to Yanis Farofakis’ And the Weak Suffer What they Must?. There are two separate points in this book—one fundamental and the other ancillary. The fundamental point is the unsustainability of the Euro as currently structured because of its capacity to crush weak nations like Greece and place severe restriction on the demos of member states. The ancillary point is the fault lines in contemporary global capitalism began to emerge when Volcker promoted controlled disintegration of the global economy and unleashed neoliberalism’s havoc, the dark, sinister creature that Varofakis calls the Global Minotaur.

The Faustian bargain that confronted Volcker when it became clear that the architecture of 1970’s system could no longer hold up was how to please both rentiers and productive capitalists under high interest rates. That bargain was for the federal government to promote a series of policies that crushed the real world prospects of American workers. As such, “the controlled disintegration Volcker unabashedly spoke of was the price poorer Americans were to pay so that the U.S. could maintain world dominance.”

By allying ourselves with the minotaur, the U.S. gained the world but lost its soul—the deeply held belief that prevailed in the post-war era but is increasingly recognized as a myth that future generation would do better than their parents. The reason why it was a bargain is Volcker, a student of the Great Depression and New Deal, recognized the tendency for the powerful to overreach and insist that the weak suffer what they must undermines “the very capacity, let along willingness” to reproduce their power.

The fundamental insight pertains to another kind of neoliberal pathology, the quest for apolitical money. The prelude to this question under Great Britain’s vision of classical liberalism was the Gold Standard. That monetary system ended in an explosive cacophony because the notion that money can be administered apolitically by technical means alone, is dangerous folly of the greatest magnitude, Varofakis writes. Yet the zombie idea of apolitical money lives on in the construction of the ECB, which is accountable to no parliament. Ultimately, the utopian vision to decouple monetary policy from political activities is destabilizing and fuels the descent into authoritarianism through deflationary pressures, Varofakis ominously warns. Descent into authoritarianism, “the dark cloud of permanent austerity”, is the natural outcome because member states are not truly free under existing EU rules. A single market and common currency, in the absence of “a powerful demos to counterbalance, stabilize, and civilize” erodes rule of law through unrestrained discretionary power.

The person that Varofakis believes to be the most prophetic on this point is, of all people, Margaret Thatcher, who believed that the Eurozone would precipitate economic crisis, tethered by EU rules that preclude national democratic responses. In this way, Thatcher echoed the argument of the influential economist Nicolas Kaldor who stated the logic that monetary union would create an inexorable force to political union was fundamentally backwards. It would impede rather than enable a more ambitious union, a wonderful alchemy. Instead, a reverse alchemy would take place where There Is No Alternative would reassert itself in an even more horrendous form, currently manifest in Greece’s Golden Dawn Party.

This book offers a powerful critique of neoliberalism as a fundamentally destabilizing force when it restrains the power of the demos in the name of technocratic efficiency. The problem is that technocratic governance is not itself insulated from destructive emotions that characterize normal human interactions including greed, revenge, and just pure wickedness (as Varofakis detailed in his conversation with a Brussels technocrat who acknowledged that austerity would not improve the financial situation of violating countries but still must be punished). These technocrats have in effect ignored the famous phrase from Winston Churchill on the reluctant desirability of democracy in our pursuit of neoliberal technocracy that seeks to insulate itself from political reactions. Political reactions will never disappear. Rather, the utopian project of insulation will only ensure that political revolts are more potent, destabilizing, and just plain ugly.

Varofakis’s current project, DiEM25, is how to protect weak nations and weak individuals from needless and damaging suffering through revitalizing the proper democratic channels. Only such a project will put the final nail in the coffin to the neoliberal era, and bring the European body politic as well as national governments everywhere back down to earth, where the reality that no system is self-correcting reigns supreme.